Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

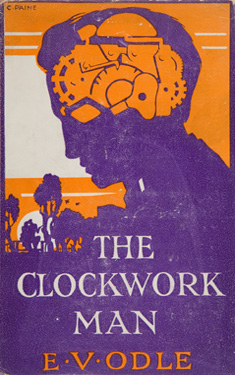

The Clockwork Man

| Author: | E. V. Odle |

| Publisher: |

William Heinemann, 1923 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

During a village cricket match, in which Great Wymering’s team is a player short, a strange person appears as if from nowhere

At first, the newcomer emits a strange whirring sound and cannot control his speech or his movements, but he recovers and is recruited by Gregg, the Great Wymering captain, as a substitute for the missing man.

Unfortunately, after hitting several balls out of sight, the stranger loses control of himself again and runs away at great speed. Tales of his subsequent bizarre behavior soon begin to circulate in the village.

Excerpt

CHAPTER ONE

The Coming of the Clockwork Man

I

It was just as Doctor Allingham had congratulated himself upon the fact that the bowling was broken, and he had only to hit now and save the trouble of running, just as he was scanning the boundaries with one eye and with the other following Tanner's short, crooked arm raised high above the white sheet at the back of the opposite wicket, that he noticed the strange figure. It's abrupt appearance, at first sight like a scarecrow dumped suddenly on the horizon, caused him to lesson his grip upon the bat in his hand. His mind wandered for just that fatal moment, and his vision of the oncoming bowler was swept away and its place taken by that arresting figure of a man coming over the path at the top of the hill, a man whose attitude, on closer examination, seemed extraordinarily like another man in the act of bowling.

That was why its effect was so distracting. It seemed to the doctor that the figure had popped up there on purpose to imitate the action of a bowler and so baulk him. During the fraction of a second in which the ball reached him, this second image had blotted out everything else. But the behavior of the figure was certainly abnormal. Its movements were violently ataxic. Its arms revolved like sails of a windmill. Its legs shot out in all directions, enveloped in dust.

The doctor's astonishment was turned into annoyance by the spectacle of his shattered wicket. A vague clatter of applause broke out. The wicket keeper stooped down to pick up the bails. The fielders relaxed and flopped down on the grass. They seemed to have discovered suddenly that it was a hot afternoon, and that cricket was, after all, a comparatively strenuous game. One of the umpires, a sly nasty fellow, screwed up his eyes and looked hard at the doctor as the latter passed him, walking with the slow, meditative gait of the bowled out, and swinging his gloves. There was nothing to do but glare back, and make the umpire feel a worm. The doctor wore an eye-glass, and he succeeded admirably. His irritation boiled over and produced a sense of ungovernable childish rage. Somehow, he had not been able to make any runs this season, and his bowling average was all to pieces. He began to think he ought to give up cricket. He was getting past the age when a man can accept reverses in the spirit of the game, and he was sick and tired of seeing his name every week in the Great Wymering Gazette as having been dismissed for a 'mere handful."

He despised himself for feeling such intense annoyance. It was extraordinary how, as one grew older, it became less possible to restrain primitive and savage impulses. When things went wrong, you wanted to do something violent and unforgivable, something you would regret afterwards, but which you would be quite willing to do for the sake of immediate satisfaction. As he approached the pavilion, he wanted to charge into the little group of players gathered around the scoring table - he wanted to rush at them and clump their heads with his bat. His mind was so full of ridiculous impulse that his body actually bolted forward as though to carry it out, and he stumbled slightly. It was absurd to feel like this, every little incident pricking him to the point of exasperation, everything magnified and translated into a conspiracy against him. Someone was manipulating the metal figure plates on the back index board. He saw a "1" hung up for the last player. Surely he had made more than One! All that swiping and thwacking, all that anxiety and suspense, and nothing to show for it! But, he remembered, he had only scored once, and that had been a lucky scramble. The fielders had been tantalisingly alert. They had always been just exactly where he had thought they were not.

He passed into the interior of the pavilion. Someone said, "Hard luck, Allingham," and he kept his eyes to the ground for fear that malice might shoot from them. He flung his bat in a corner and sat down to unstrap his pads. Gregg, the captain, came in. He was a cool, fair young man, fresh from Cambridge. He came in grinning, and only stopped when he saw the expression on Allingham's face.

"I thought you were pretty well set," he remarked casually.

'so I was," said Allingham, aiming a pad at the opposite wall. 'so I was. I never felt more like it in my life. Then some idiot goes and sticks himself right over the top of the sheet. An escaped lunatic, a chap with a lot of extra arms and legs. You never saw anything like it in your life!"

"Really," he remarked presently, 'six wickets down, and all the best men out. We look like going to pieces. Especially as we're a man short."

"Well I can't help it," said Allingham, "you don't expect a thing like that to happen. What's the white sheet for? So you can see the bowler's arm. But when something gets in the way, just over the sheet - just where you've got your eyes fixed. It wouldn't happen once in a million times."

"Never mind," said Gregg, cheerfully, "it's all in the game."

"It isn't in the game," Allingham began. But the other had gone out.

Allingham stood up and slowly rolled down his sleeves and put on his blazer. Of course, Gregg was like that, a thorough sportsman, taking the good with the bad. But then he was only twenty-four. You could be like that then, so full of life and high spirits that generosity flowed from you imperceptibly and without effort. At forty you began to shrivel up. Atrophy of the finer feelings. You began to be deliberately and consistently mean and narrow. You took a savage delight in making other people pay for your disappointments.

He looked out of the window, and there was that confounded figure still jiggling about. It had come nearer to the ground. It hovered, with a curious air of not being related to its surroundings that was more than puzzling. It did not seem to know what it was about, but hopped along aimlessly, as though scenting a track, stopped for a moment, blundered forward again and made a zig-zag course towards the ground. The doctor watched it advancing through the broad meadow that bounded the pitch, threading its between the little groups of grazing cows, that raised their heads with more than their ordinary, slow persistency, as though startled by some noise. The figure seemed to be aiming for the barrier of hurdles that surrounded the pitch, but whether its desire was for cricket or merely to reach some kind of goal, whether it sought recreation or a mere pause from its restless convulsions, it was difficult to tell. Finally, it fell against the fence and hung there, two hands crooked over the hurdle and its legs drawn together at the knees. It became suddenly very still - so still that it was hard to believe it had ever moved.

It was certainly odd. The doctor was so struck by something altogether wrong about the figure, something so suggestive of a pathological phenomenon, that he almost forgot his annoyance and remained watching it with an unlighted cigarette between his lips.

II

There was another person present at the cricket match to whom the appearance of the strange figure upon the hill seemed an unusual circumstance, only in his case it provided rather an agreeable diversion than an irritating disturbance. It had been something to look at, and much more interesting than cricket. All afternoon Arthur Withers had been lying in the long grass, chewing bits of it at intervals and hoping against hope that something would happen to prevent his having to go out to the pitch and make a fool of himself. He knew perfectly well that Tanner, the demon bowler of the opposing team, would get him out first ball. He might linger at the seat of operations whilst one or two byes were run; but there were few quests more unwarranted and hopeless than that excursion, duly padded and gloved, to the scene of instant disaster. He dreaded the unnecessary trouble he was bound to give, the waiting while he walked with shaking knees to the wicket; the careful assistance of the umpire in finding centre for him; all the ceremony of cricket rehearsed for his special and quite undeserved benefit. And afterwards he would be put to field where there was a lot of running to do, and only dead balls to pick up. Of course he wasn't funking; that wouldn't be cricket. But he had been very miserable. He sometimes wondered why he paid a subscription to take part in the game that cost him such agony of mind to play. But it was the privilege that mattered as much as anything. Just to be allowed to play.

Arthur was accustomed to be allowed to do things. He accepted his fate with a broad grin and determination to do whatever was cricket in life. Everybody in Great Wymering knew that he was a bit of a fool, and rather simple. They knew that his career at the bank had been one wild story of mistakes and narrow escapes from dismissal. But even that didn't really matter. Things happened to him just as much as to other and more efficient individuals, little odd circumstances that made the rest of life curiously unimportant by comparison. Everyday, for example, something humorous occurred in life, something that obliterated all the worries, something worth waking up in the middle of the night to laugh at it again. That is why the appearance of the odd looking figure had been so welcome to him. It was distinctly amusing. It had made him forget his fears. Like all funny things or happenings, it made you for the moment impersonal.

He was so interested that presently he got up and wandered along the line of hurdles towards the spot where the strange figure had come to rest. It had not moved at all, and this fact added astonishment to curiosity. It clung desperately to the barrier, as though glad to have got there. Its attitude was awkward in the extreme, hunched up, ill-adjusted, but it made no attempt to achieve comfort. Further along, little groups of spectators were leaning against the barrier in nearly similar positions, smoking pipes, fidgeting wand watching the game intently. But the strange figure was not doing anything at all, and if he looked at the players it was with an unnatural degree of intense observation. Arthur walked slowly along, wondering how close he could get to his objective without appearing rude. But, somehow, he did not think this difficulty would arise. There was something singularly forlorn and wretched about this curious individual, a suggestion of inconsequence. Arthur could have sworn that he was homeless and had no purpose or occupation. He was not in the picture of life, but something blobbed on by accident. Other people gave some sharp hint by their manner or deportment that they belonged to some roughly defined class. You could guess something about them. But this extraordinary personage, who had emerged so suddenly from the line of the sky and streaked aimlessly across the landscape, bore not even the vaguest marks of homely origin. He had staggered along the path, not with the recognisable gait of a drunken man, but with a sort of desperate decision, as though convinced in his mind that the path he was treading was really only a thin plank stretched from heaven to earth upon which he had been obliged to balance himself. And now he was hanging upon the hurdle, and it was just as though someone had thrown a great piece of clay there, and with a few deft strokes shaped it into the vague likeness of a man.

III

As he drew nearer, Arthur's impression of an unearthly being was sobered a little by the discovery that the strange figure wore a wig. It was a very red wig, and over the top of it was jammed a brown bowler hat. The face underneath was crimson and flabby. Arthur decided that it was not a very interesting face. Its features seemed to melt into each other in an odd sort of way, so that you knew that you were looking at a face and that was about all. He was about to turn his head politely and pass on, when he was suddenly rooted to the ground by the observation of a most singular circumstance.

The strange figure was flapping his ears - flapping them violently backwards and forwards with an almost inconceivable rapidity!

Arthur felt a sudden clutching sensation in the region of his heart. Of course, he had heard of people being able to move their ears slightly. That was common knowledge. But the ears of this man positively vibrated. They were more like the wings of some strange insect than human ears. It was a ghastly spectacle - unbelievable, yet obvious. Arthur tried to walk away; he looked this way and that, but it was impossible to resist the fascination of those flapping ears. Besides, the strange figure had seen him. He was fixing him with eyes that did not move in their sockets, but stared straight ahead; Arthur had placed himself in the direct line of their vision. The expression in the eyes was compelling, almost hypnotic.

"Excuse me," Arthur ventured, huskily, "did you wish to speak to me?"

The strange figure stopped flapping his ears and opened his mouth. He opened it unpleasantly wide, as though trying to yawn. Then he shut it with a sharp snap, and without yawning. After that he shifted his whole body very slowly, as though endeavoring to arouse himself from an enormous apathy. And then he appeared to be waiting for something to happen.

Arthur fidgeted, and he looked nervously around him. It was an awkward situation, but after all, he had brought it on himself. He did not like to move away. Besides, having started the conversation it was only common politeness to wait until the stranger offered a remark. And presently, the latter opened his mouth again. This time he actually spoke.

"Wallabaloo - Wallabaloo - Bompadi - Bompadi - Wum. Wum - Wum - nine and ninepence ..." he announced.

"I beg your pardon," said Arthur hastily.

"Wallabaloo," replied the other, eagerly. "Walla - Oh, hang it - Hulloa, no we've got it - Wallabaloo - No, we haven't - Bang Wallop - nine and ninepence -"

Arthur swallowed several times in rapid succession. His mind relapsed into a curious state of blankness. For some minutes he was not aware of any thinking processes at all. He began to feel dizzy and faint, from sheer bewilderment. And then the idea of escape crept into his consciousness. He moved one foot, intending to walk away. But the strange figure suddenly lifted up a hand, with an abrupt, jerky movement, like a signal jumping up. He said "nine and ninepence" three times very slowly and solemnly, and flapped his right ear twice. In spite of his confusion, Arthur could not help but noticing the peculiar and awful synchronisation of these movements. At any rate, they seemed to help this unfortunate individual out of his difficulties. Still holding a hand upright, he achieved his first complete sentence.

"Not an escaped lunatic," he protested, and tried to shake his head. But the attempt to do so merely started his ears flapping again.

And then, as though exhausted by these efforts, he relapsed altogether into a sort of lumpiness and general resemblance to nothing on earth. The hand dropped heavily. The ears twitched spasmodically, the right one reversing the action of the left. He seemed to sink down, like a deflated balloon, and a faint whistling sigh escaped his lips. His face assumed an expression that was humble in the extreme, as though he were desirous of apologising to the air for the bother of keeping him alive.

Arthur stared, expecting every moment to see the figure before him fall to the ground or even disappear through the earth. But just when his looseness and limpness reached to the lowest ebb a sudden pulse would shake the stranger from head to foot; noises that were scarcely human issued from him, puffings and blowings, a sort of jerky grinding and grating. He would rear up for a moment, appear alert and lively, only to collapse again, slowly and sadly, his head falling to one side, his arms fluttering feebly like the wings of a wounded bird.

Arthur's chief sensation was one of pity for a fellow creature obviously in such hopeless state. He almost forgot his alarm in his sympathy for the difficulties of the strange figure. That struggle to get alive, to produce the elementary effects of existence, made him think of his own moods of failure, his own helplessness. He took a step nearer to the hurdle.

"Can I do anything for you?" he enquired, almost in a whisper. Suddenly, the strange figure seemed to achieve a sort of mastery of himself. He began opening and shutting his mouth very rapidly, to the accompaniment of sharp clicking noises.

"Its devilish hard," he announced, presently, "this feeling, you know - Click - All dressed up and nowhere to go - Click - Click - "

"Is that how you feel?" Arthur enquired. He came nearer still, as though to hear better. But the other got into a muddle with his affirmative. He flapped an ear in staccato fashion, and Arthur hastily withdrew.

Now, the afternoon was very warm and very still. Where they stood the only sounds that could reach them were the slight crack of the batted ball, and the soft padding of the fielders. That was why the thing that happened next could hardly be mistaken. It began by the strange figure suddenly putting both hands upon the hurdle and raising himself up about an inch off the ground. He looked all at once enormously alive and vital. Light flashed in his eyes.

"Eureka!" he clicked, "I'm working!"

"What's that?" shouted Arthur, backing away. "What's that you said?"

"L-L-L-L-L-L-Listen," vibrated the other.

Still pressing his hands on the hurdle, he leaned upon them until the top part of his body hung perilously over. His face wore an expression of unutterable relief.

"Can't you hear," he squeaked, red in the face.

And then Arthur was quite sure about something that he had been vaguely hearing for some moments. It sounded like about a hundred alarum clocks all going off at once, muffled somehow, but concentrated. It was a sort of whirring, low and spasmodic at first, but broadening out into something more regular, less frantic.

"What that noise?" he demanded thoroughly frightened by now.

"It's only my clock," said the other. He clambered over the hurdle, a little stiffly, as though not quite sure of his limbs. Except for a general awkwardness, an abrupt tremor now and again, he seemed to have become quite rational and ordinary. Arthur scarcely comprehended the remark, and it certainly did not explain the origin of the harassing noise. He gaped at the figure - less strange now, although still puzzling - and noticed for the first time his snuff coloured suit of rather odd pattern, his boots of curious leaden hue, his podgy face with a snub nose in the middle of it, his broad forehead surmounted by the funny fringe of the wig. His voice, as he went on speaking, gradually increased in pitch until it reached an even tenor.

"Perhaps I ought to explain," he continued. "You see, I'm a clockwork man."

"Oh," said Arthur, his mouth opening wide. And then he stammered quickly, "that noise, you know."

The Clockwork man nodded quickly, as though recollecting something. Then he moved his right hand spasmodically upwards and inserted it between the lapels of his jacket, somewhere in the region of his waistcoat. He appeared to be trying to find something. Presently he found what it was he looked for, and his hand moved again with a sharp, deliberate action. The noise stopped at once. "The silencer," he explained, "I had forgot to put it on. It was such a relief to be working again. I must have nearly stopped altogether. Very awkward. Very awkward, indeed."

He appeared to be addressing the air generally.

'the fact is I need a good overhauling. I'm all to pieces. Nothing seems right. I oughtn't to creak like this. I'm sure there's a screw loose somewhere."

He moved his arm slowly round in a circle, as though to reassure himself. The arm worked in a lop-sided fashion, like a badly shaped wheel, stiffly upwards and then quickly dropping down the curve. Then the Clockwork man lifted a leg and swung it swiftly backwards and forwards. At first the leg shot out sharply, and there seemed to be some difficulty about its withdrawal; but after a little practice it moved quite smoothly. He continued these experiments for a few moments, in complete silence and with a slightly anxious expression upon his face, as though he were really afraid things were not quite as they should be.

Arthur remained in stupefied silence. He did not know what to make of these antics. The Clockwork man looked at him, and seemed to be trying hard to remould his features into a new expression, faintly benevolent. Apparently, however, it was a tremendous effort for him to move any part of his face; and any change that took place merely made him look rather like a caricature of himself.

"Of course," he said slowly, "you don't understand. It isn't to be expected that you would understand. Why, you haven't even got a clock! That was the first thing I noticed about you."

He came a little nearer to Arthur, walking with a hop, skip and jump, rather like a man with his feet tied together.

"And yet, you look like an intelligent sort of being," he continued, "even though you are an anachronism."

Arthur was not sure what this term implied. In spite of his confusion he couldn't help feeling a little amused. The figure standing by his side was so exactly like a wax-work come to life, and his talk was faintly reminiscent of a gramophone record.

"What year is it?" enquired the other suddenly, and without altering a muscle of his face.

"Nineteen hundred and twenty-three," said Arthur smiling faintly.

The Clockwork man lifted a hand to his face, and with some difficulty lodged a finger reflectively against his nose. "Nineteen hundred and twenty-three," he repeated, "that's interesting. Very interesting, indeed. Not that I have use for time, you know."

He appeared to ruminate, still holding a finger against his nose. Then he shot his left arm out with a swift, gymnastic action and laid the flat palm of his hand upon Arthur's shoulder.

"Did you see me coming over the hill?" he enquired.

Arthur nodded.

"Where did you think I came from?"

'to tell the truth," said Arthur, after a moment's consideration, "I thought you came out of the sky."

The clockwork man looked as though he wanted to smile and didn't know how. His eyes twinkled faintly, but the rest of his face remained immobile, formal. "Very nearly right," he said, in quick, precise accents, "but not quite."

He offered no further information. For a long while Arthur was puzzled by the movements that followed this last remark. Apparently the Clockwork man desired to change his tactics; he did not wish to prolong the conversation. But, in his effort to move away, he was obviously hampered by the fact that his hand still rested upon Arthur's shoulder. He did not seem to be able to bend his arm in a natural fashion. Instead, he kept on making a half-right movement of his body, with the result that every time he so moved he was stopped by the impingement of his hand against Arthur's neck. At last he solved the problem. He took a quick step backwards, nearly losing his balance in the process, and cleared his arm, which he then lowered in the usual fashion. Then he turned sharply to the left, considered for a moment, and waddled away. There was no other term in Arthur's estimation, to describe his peculiar gait. He took no stride; he simply lifted one foot up and then the other, and then placed them down again slightly ahead of their former positions. His body swayed from side to side in tune with his strange walk. After he had progressed for a few yards he turned to the right, with a smart movement, and looked approximately in Arthur's direction. His mouth opened and shut very rapidly, and there floated across the intervening space some vague and very unsatisfactory human noise, obviously intended as n expression of leave-taking. Then he turned to the left again, with the same drill like action, and waddled along.

IV

Arthur watched him, feeling diffident, half inclined to follow him in case he fell over. For there was not much stability about the Clockwork man. It was clear the slightest obstacle would have precipitated him upon his nose. He kept his head erect, and looked neither downwards or to right and left. He seemed wholly absorbed in his eccentric mode of locomotion, as though he found it interesting just to be moving along. Arthur kept his eyes glued upon that stiff, upright back, surmounted by the wig and hat, and he wondered what would happen when the Clockwork man reached to the end of the line of hurdles, where another barrier started at right angles across the end of the cricket ground.

It was a sight to attract attention, but fortunately, as Arthur thought, everyone seemed too absorbed in the game to notice what was happening. The dawning of humour saved him from some uncomfortable misgivings. There was something uncanny about the experience. Somehow, it didn't seem natural, but it was certainly funny. It was grotesque. You had to laugh at the odd-looking figure, or else feel cold all over with another kind of sensation. Of course, this man was mad. He was, in spite of his denial, an escaped lunatic. But the noise? That was certainly difficult to explain. Perhaps he had some kind of infernal machine hidden in his pocket, in which case he would be a dangerous kind of lunatic.

What was he going to do next? He had reached to the end of the field and stopped abruptly. Apparently, the presence of another barrier acted as a complete check to further movement. For several seconds he remained perfectly still. He was now about a hundred yards from Arthur, but the latter had good eyesight, and he was determined to miss nothing.

Then the Clockwork man raised a hand slowly to his face, and Arthur knew he was repeating his former meditative action, finger to nose. He remained in that position for another minute, as though the problem of which way to turn was almost too much for him. Finally, he turned sharp to the right and began to walk again.

Arthur became aware of two other figures approaching the one he was watching so intently. They were Gregg, the captain of the team, and Doctor Allingham. The yellow braid on their blazers shone in the sunlight, and Arthur could see the blue emblem on Gregg's pocket. There would have to be a meeting. The two flannelled figures were strolling along in a direct line towards that other oddly insistent form. Arthur caught his breath. Somehow he dreaded that encounter. When he looked again there was some kind of confabulation going on. Curiously enough, it was Doctor Allingham and Gregg who seemed incapable of movement now. They stood there, with their hands in their pockets, staring, listening. But the Clockwork man was apparently making the utmost use of his limited range of action. His arms were busy. Sometimes he kicked a leg up, as though to emphasise some tremendously important point. And now and again he jabbed a finger outwards in the direction of the field of play. Arthur caught the sound of a high, squeaky voice borne upon the breeze.

Whatever the argument was about, the Clockwork man seemed to gain his point, for presently the three figures turned together and proceeded in a bee-line towards the pavilion, Doctor Allingham and Gregg dodging about absurdly in their effort to accommodate themselves to the gyrations of their companion.

Copyright © 1923 by E. V. Odle

Reviews

Images

Full Details

Full Details