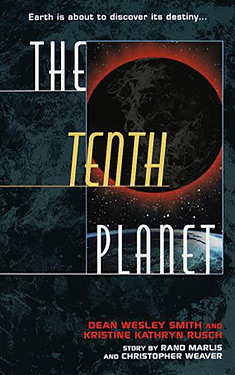

The Tenth Planet

| Author: | Kristine Kathryn Rusch Dean Wesley Smith |

| Publisher: |

Del Rey / Ballantine, 1999 |

| Series: | The Tenth Planet: Book 1 |

|

1. The Tenth Planet |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

2017: NEAR THE PLANET URANUS

After a deep-space satellite mysteriously stops transmitting, the Hubble III telescope picks up a startling image. Astronomers don't know what the strange object is--only that it orbits past Earth every two millennia.

Meanwhile, archaeologist Leo Cross has discovered peculiar layers of black residue at dig sites around the globe. Stranger still, these thin bands occur like clockwork every 2,006 years, coinciding with some of the world's darkest moments in history.

We have six months to prepare for the next arrival. This time we know something is coming. This time we have weapons to defend us.

This time we'll be wrong... again.

Excerpt

August 16, 2017: 16:04 Universal Time

240 Days Until Arrival

International Space Monitoring Buoy Number Six was alone. Since it had left Earth over three years ago, it had been alone, traveling through the depths of space to the seventh planet, Uranus, then settling into a wide elliptical orbit. For the past six months, ISMB 6 had faithfully done its job, taking readings of the surface of the planet, using its cameras and sensors and equipment to explore the outer reaches of the solar system.

ISMB 6 was a hardworking little craft, although from the outside it seemed like little more than a piece of space junk in an area devoid of anything else man-made. A silver craft, the diameter of a small bedroom, its surface was cluttered with a myriad of dishes, antennas, and measuring devices, making it look like a spider. On the side of the craft, in one of the only small, open areas of the main body, were the letters ISMB followed by the number 6. Under the letters were a dozen tiny stencils of flags, indicating the countries that had helped in the joint project.

Out here, everything familiar seemed remote. Even the sun was nothing more than a distant hole of light in the massive field of stars, not even strong enough to cast real shadows, or supply any real warmth.

Not that ISMB 6 cared. It was one of seven buoys designed by American and Japanese engineers, and sent outward by a consortium of twelve countries, all believing that the heavens needed to be monitored as the seas were once monitored. The early scientists saw the ISMB system as a twofold project: the buoys would act as ways to gather information in deep space, and they would also serve as the markers of Earth's boundaries.

Surprisingly, the nations making up the consortium did not want to consider the boundary issue. To them, having boundaries meant defending them, sending weapons into space, perhaps even developing a fleet.

Such things are not necessary, the politicians said, unless there is a perceived threat. And of course, there was no threat and no hint of one ever appearing. The politicians believed we were alone. The scientists weren't sure.

So the consortium took its funding and built the seven buoys, launching them over a three-year period. Three buoys orbited the three largest planets in the solar system: Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. Two buoys were stationed over the sun's poles, holding positions above and below the plane of the solar system at a distance from the sun about the same as Mars. The seventh was completing the last year of its flight to catch and orbit Pluto.

All seven sent a constant stream of data Earthward, powered by batteries designed to last thirty years, even without solar reenergizing. The data was received at stations all over Earth and relayed to a classroom-sized area three floors under a complex outside of Sydney, Australia. The complex housed, at times, upwards of a hundred scientists from around the world, studying on-site the information being sent back from the buoys.

At the complex, ISMB 6 was the only buoy that hadn't been assigned a nickname. The nicknames suggested by the English-speaking scientists were too crude to use, even accidentally, at press conferences, and besides, the jokes did not translate well into the complex's other approved languages. As a result, the scientists who tried to create a shred of personality in their tools imagined ISMB 6 as a serious, unimaginative little worker, who could be relied upon at all times.

ISMB 6 wasn't aware of any of this. ISMB 6 really wasn't aware of anything. It simply went about its job, orbiting Uranus, sending telemetry back to Earth. It's entire mission was routine, as routine as a pioneering mission could be until ISMB 6's third orbit of the day, a day artificially measured in Earth time.

As ISMB 6 rose slightly above and beyond the dark, cold surface of Uranus, a blackness seemed to loom near the little craft, almost as if an invisible cloud of soot was filling space.

Then, with a weak, reflected flash of light from the darkness, all data stopped flowing toward Earth.

All instruments shut down.

ISMB 6, the faithful, hardworking little buoy, was dead.

August 16, 2017: 4:56 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time

240 Days Until Arrival

Orange and yellow bands of light cut through the morning mist as the sun peeked above the Coast Mountain Range. The morning air had a thick dampness that felt more appropriate to winter than to August, yet by noon the chill would be gone and the temperature would hit eighty.

Dr. Edwin Bradshaw ducked out of his tent and pulled his jacket tight around his shoulders, shivering slightly in the cool morning air. A mile to the west the Pacific Ocean rumbled as the surf hit the beach. He couldn't see the water--the tall pine trees that surrounded him prevented that--but he could hear the ocean. Its sound was constant, sometimes a low murmur and sometimes an angry explosive pounding. And sometimes this rumble.

He found that the ocean's constant conversation soothed him. He knew he would miss it, as he always did, when he had to go back to the Valley. He would miss all of this. He was lucky to have ended up here, in Oregon, rather than some podunk university somewhere, a place with no credentials and no budget to send him anywhere. Oregon State University liked his background, despite the controversies, and for the most part, the administration left him alone. He was able to choose his dig sites, and his assistants, and use university funds to continue his research. Fortunately for him, his research centered on the Native American tribes of the Oregon Coast, and he got to spend his summers, and an occasional winter, in what he considered to be the most beautiful place on Earth.

But he was getting older. The morning chill got into his bones these days. In September, he would turn sixty, and lately, he had begun to feel it. Sleeping in a tent, even with a thick sleeping bag and an air mattress (something he wouldn't have considered in the old days), left him stiff and sore. It took a few minutes of movement every morning before his joints stopped creaking.

No one stirred in the dozen other tents around the small clearing. Twenty-four Oregon State University students had signed up for this dig, more than any other summer. He was having trouble just keeping them all busy. The dig site wasn't big enough for all of them to work at once.

He grinned. He always woke before his students. On the second day of the dig, most of them had groaned their way through the work, and he hadn't felt old at all. These days students got no exercise, except for the federally mandated stuff in the public schools. Remotes, handheld computers, and the new personal assistants, which were little more than headless robots, ensured that anyone who wanted to spend his life in a chair could do so without any effort at all.

Bradshaw was an old-fashioned guy, old enough to remember when kids spent their summers outside playing baseball and kick the can until their parents forced them inside. Old enough to remember when color television was an unusual thing. Old enough to remember only three television channels--all free--and changing those channels by twisting a dial. When he was a little, little boy, it had taken him two hands to go from one channel to the other.

Now some of his students brought their own televisions with them, tiny things that attached to the wrist and changed channels with a soft verbal command. On the first day of the dig, he had Kelly Flynn, his graduate assistant, help him with what he called the Great Electronics Search. He confiscated most of his students' "necessities"--generally, watches that served as small computers, with television, radio, gaming, and Internet capability. He wanted them to focus on the lives of Native Americans before white settlers found this beautiful place. His theory was that if his students were able to think like the tribe that filled this area, they would do better when they searched through the earth for remnants of that life.

He hated the day of the Great Electronics Search. It made him the most unpopular man in camp for the first week of the dig. But he had done it often enough to know that by the end of the summer, his students would thank him. They would say things like "I really got to enjoy the woods, Doc. I'd never done that before."

And never would again, he would wager.

Most of those students would be angry if they knew that Bradshaw always brought his own electronic equipment to the dig site. They would be even more upset if they knew that he spent part of his evenings on-line, keeping track of current research. His favorite on-line site was a place he lurked, a place where some of the best archaeological minds of this generation argued theory in terms that were as far beyond these students as computers were beyond the tribes that once lived in this very spot. Bradshaw's only contribution to the site--for that matter, to most archaeological publications, print or on-line--was to list the location of his dig and the reason he was excavating the site.

Imagine his surprise when he was awakened this morning by the vibration of his watch against his wrist. He had only set that private computer alarm for messages marked urgent, be they phone, fax, or e-mail.

This one was an e-mail message, sent only a few hours after he had updated the dig information for the archaeological site. It was from Dr. Leo Cross. Cross was not the world's most famous archaeologist. Bradshaw had no respect for the famous people, the brand names, to whom recognition was more important than research. They usually let their grad students handle the hard work, and then took credit for the findings. No. Cross was the best-known archaeological historian among his peers. They all envied his intuitive ability. It was almost as if the earth spoke to him, revealing to him secrets that none of the others could ever hope to hear.

The thing that made Cross s...

Copyright © 1999 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Copyright © 1999 by Dean Wesley Smith

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details