Added By: Weesam

Last Updated: Administrator

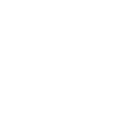

The Secret Market of the Dead

| Author: | Giovanni De Feo |

| Publisher: |

Saga Press, 2025 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Just beyond the waking edges of Lucerìa, an 18th-century town in the kingdom of Naples, lies the Night: an enigmatic fiefdom governed by seven immortals and fueled by Moira, the power to reshape one's destiny.

On this porous border separating Day from Night, Oriana spends her time fantasizing about becoming a smith in her father's forge and eavesdropping on whispered tales of beasts and men who roam the nocturnal realm. But in the Night, these stories come alive, as Oriana saw for herself after she inadvertently trespassed into the Secret Market of the Dead, where vendors hawk Moira to those desperate enough to accept its immeasurably steep price.

Years later, when her father chooses her twin brother to succeed him, Oriana challenges her sibling to a series of trials to determine the forge's true heir. But as the twins' fierce competition escalates, with the town and her own family set firmly against her, Oriana realizes that to break free from the stifling confines of Day, she must once again embrace the Night - and, as always, everything comes with a cost.

Excerpt

Chapter One

ONE

During the first week of May 1747, as the saints’ procession honoring the birth of King Don Carlos’s heir made its way past Oriana’s house, her twin brother Oriano suddenly dove in front of the cortege and was almost trampled to death. Nothing short of a miracle saved him, a miracle to which Oriana was the sole witness.

Oriana and Oriano spent almost the entire night before the parade in games and whispered expectations. The twins’ bedroom, a narrow attic space, also served as a drying room for the festoons of oregano and dried peppers that hung from the rafters. Two glass jars full of fireflies emanated a greenish glow that barely lit the game they were playing. Their corn husk–stuffed mattress swished every time they moved to turn over a card. On a patched blanket, holy cards smudged by use were arranged in four rows of five. The eight-year-old twins sat across from each other and stared at them in concentration.

“My turn,” said Oriana.

“That one,” replied her twin, pointing at a card.

“Right. That’s… Saint Barbara, protector of miners, prayed to for protection against lightning, and her day is the… third, no, the fourth of December. Turn it!”

Oriano turned over the card and held it close to the jar to reveal a young girl crowned in gold, a tower being struck by a lightning bolt in the background. The little boy slapped his knee.

“You’re cheating! I know you are. Just tell me how you do it!”

“I am not. I just have a good memory. Now, that’s six against one. Your turn. That one,” she said, pointing at a card on the edge of the bed.

“Can I have a peek first?”

“Of course not. You know what Papà says. It’s no use agreeing to something if you break your word after.”

“Well, I haven’t agreed to lose six to one!”

“Just play your turn, Oriano.”

“All right, then. That’s… I think Saint Simon, patron of the leather people—”

“That would be the tanners.”

“Tanners, that’s what I said. Prayed to for… chicken, I mean, when you want to eat chicken, or have your chickens get fat. Am I right?”

“Go on.”

“And his day… his day is… can I have a hint?”

“Oh, I should think not.”

“You are the worst! His celebration day is… ah!” he said, suddenly beaming. “I know it! It’s the day Mamma and Papà married! I know because it’s coming in two Sundays, so it’s the fifteenth of May! Turn it over!”

Oriana turned over the card: an old man with a flame in his hand and a piglet at his feet stared at them with hollow eyes.

“Saint Anthony, protector of all smiths,” said Oriana, “sorry.”

“I’m done. I don’t want to play your stupid game anymore,” he said, and shook the coverlet, showering all the cards on the floor.

“Oriano! Those are Mamma’s holy cards! If they get filthy, she’ll only feed us bread and water for a week!”

“I don’t care. You cheated, you just won’t admit it!”

“I did not!”

“Yes, you did!”

A thump interrupted their quarrel. The twins jumped and stared at the trapdoor.

“I’m hearing a ruckus,” sounded Donna Lena’s muffled voice, “when I should be hearing prayers or silence. Need I come up?”

“Sorry, Mamma,” said Oriana. “We were just about to go to sleep.”

“You’d better. You still want to see the saints’ procession tomorrow, don’t you?”

“Yes!” the twins replied in unison.

“Then you must be on your best behavior. And if you lose one of my holy cards, I’ll shave your heads to shame you both. Do I make myself clear?”

“Yes, Mamma,” they sang together.

“Buonanotte.”

Quickly, the twins collected the cards from the floor, draped a black cloth over the firefly lanterns—leaving one alight so they could see a bit—and slipped under the sheets. In that cozy half darkness, the siblings breathed face-to-face, their foreheads touching. Oriana was the taller of the two, and slightly stockier, but both had the thick eyebrows of the Siliceo family, unruly brown hair, and their mother’s mischievous green-gray eyes.

“Do you think Papà will finally get a commission?” Oriano asked.

“I heard Mamma pray to Saint Anthony for it, so maybe he will.”

“Will the statue of Saint Anthony be there tomorrow?”

“Why? Are you still thinking about your spinning top?”

“Well,” he sniffed, “I wouldn’t have to ask Saint Anthony for it if Papà had bought me a new one.”

“If he could have, he would have.”

“And why shouldn’t I ask Saint Anthony? Or perhaps I could call the Night-One, the Duke of Under-earth, to come in his stead!”

While no one had seen the Duke manifest in nearly a hundred years, as patron of smiths and craftsmen and the earthliest of the seven Major Ones, his mere presence was said to grant gifts. Oriana stuck her head out of the blanket, as if to make sure they were still alone, then dove under again. She brought her forehead against her brother’s.

“You know Mother would kill you if she heard you speak their names.”

Being from Naples, their mother found the whole concept of Night Saints blasphemous, and hated all their silly rites. The only time she seemed to bear the idea was during Vigils, and even there she would pointedly make the sign of the cross. Luckily, Oriana’s Aunt Ciccerella thought otherwise. The girl remembered well how her aunt lay in bed with her on New Year’s Eve, whispering of the Night.

All Nocturnals were Diurnals once, the way all those who are now alive, one day will die. Some of the dead are told, and those who are sometimes come back, but with something of the Night, something wild and old.

Aunt Ciccerella told her that Nocturnals only existed when Diurnals told stories about them, especially at Night. She then listed the seven Major Ones, each an earl of their own domain, a part of the immortal darkness.

Should you need to call for their help, these are their names. Ossifrago, Baron of Twilight and Jester of the Night King. Uriene, Earl of the First Night, prophet, and dice master. The Emistuchivio, Duke of the dark that lies Under-earth. Briace, Marquise of Fullmoon and Lord of were-creatures and lunatics. Serapide, Countess of Second Night, she-warrior, and bringer of dreams. The Grim King himself, Lord ruler of the Hour of the Wolf and of all Night. And finally his spouse, Queen of Dawn and our Lady of sorrows.

Few adults she knew would dare utter their names at night, even for protection. And yet calling out to them, daring them to respond, made Oriana feel safer, stronger. All her life she imagined seeing Nocturnals out of the corner of her eye. When at dusk the branch of a pine tree quivered overhead, she imagined the spiny face of a Mazapegul. And when the railing of a staircase shifted under the moonlight, Oriana thought it a Wyrm slithering over the palazzo to get a better look at her. Sometimes at night she heard songs in the wind. She could never remember their words, only a tingling sensation, like her whole body was on fire. Was that the Night? Though she had called out to it several times, she received an answer only once—the year prior, after Oriano returned from the spring market in Foggia.

In hindsight, she wasn’t so sure that it hadn’t been a dream. Not that sleep would have made it any less real, for the Night-Ones come out of dreams like swallows from chimneys. She remembered lying with her eyes wide open until she felt the dark pressing in on her from all sides. And when she stood up to open the small window above her bed, the sky was ablaze with stars. She stared at them for so long she forgot herself completely; she wasn’t a little girl looking at the Night, she was the Night looking at a little girl.

Then, she saw it. A cloud of stars descended onto the roof and took the shape of a man. Had it been summer, Oriana would have thought them fireflies, but it was still too cold.

And if you see fireflies in early spring or winter, be careful. Garaudi wear cloaks made of eyes—stolen from vagrants—that glint in the dark. For they were makers of sublime beauty but refused to see it until it was too late. And so the Duke of the Under-earth punished them by turning them blind.

It seemed like the creature was looking in Oriana’s direction, though she couldn’t know for certain. She ought to have felt scared under its gaze but didn’t. It was blind, after all, slave to the Under-earth and its master. Poor, poor Garaude. The creature came ablaze, its cloak-eyes opening. Right in the middle of its form, she could make out a hood, and in that blackness, she imagined salty lips, soundlessly forming an O.

She had said its name. Was it saying hers?

She wanted to tell Oriano straightaway, of course. But even then, Oriana felt that the experience was meant for her and her alone. He had gone to the spring market without her, hadn’t he? When her mother caught a fever, it was she who had to stay behind and help her in the house. He had the Day, and so she would claim the Night. Also, if she told him, sooner or later he would tell Mamma.

“If the Duke came,” Oriano whispered under the bed covers, “I could ask him for a spinning top made of darkness, fire, stars, or wind. Can you imagine? Me spinning my top in front of our house and all the hats in Lucerìa flying high!”

“The Emistuchivio,” she hissed, drawing closer, “will not come for a little boy. And anyway, you have nothing to offer him.”

“But I do!” He beamed.

He emerged from underneath the blanket and walked over to a hole in the wall of their room. Carefully, by the fireflies’ low glow, the boy retrieved a ball of cotton and unwrapped it to reveal two teeth. Sitting up, Oriana frowned at her twin.

“Don’t the Tellers say,” he began, cheeks flushed, “that the Duke sows children’s teeth in the ground to grow his bone soldiers?”

“Who on earth did you hear that from?”

“From Aunt Ciccerella, at the Vigil of the Dead last year.”

“And you’ve kept your baby teeth hidden in that wall for, what… months?”

“Think about it, two teeth, two Boons from the Duke!”

“That’s greedy.”

“I wanted you to have one. Isn’t there anything you want?”

She bit her lip. There was something she wanted. It was the very reason she had felt such disappointment when Oriano was allowed to go to the spring market in Foggia and she had to stay home. But she didn’t even dare think it, much less say it aloud.

“Oriano, if Mother sees this, she’ll bring Hell upon us. You won’t get to go to the spring market, and neither will I.”

“I’ll keep them hidden.”

“Promise me, then. Swear.”

He swore. They slid back under the blanket, whispering about secret keys that led to secret chests, which held all the treasures of the Under-earth. And even though at times Oriana tried to stifle her brother’s excitement, she was no longer able to quench her own. That night, they slept little, if at all.

The Day surprised them with a fullness of light that spelled disaster. Their father was still not back from his errand, and neither was their mother. She had gone to spin at Mamma Eba’s workshop with an old companion from Caserta, and the twins were expected to be clean and ready to go when she returned. Oriano was still too excited to be of any real help, so Oriana had to get the water from the public fountain in the piazza herself.

On her way home she caught a glimpse of her father’s workshop, just three houses down the street. For a moment, the little girl was transfixed. She breathed in its scent: coal, iron, sawdust. Despite her enthrallment, she wouldn’t take a single step toward it; an old superstition in Lucerìa warned against a smith’s children entering his workshop before they came of age. But the smithy’s deep oak door was slightly ajar, and Oriana could glimpse inside from where she stood. By the forge’s light, she spotted the square anvil and her father’s hammer resting atop it. It was an old, ugly beast, dented and blackened by use. And yet in her father’s hands, it could create wonders.

A draft made the smithy’s door creak shut and the girl hurried home, careful not to spill the water. In a flurry of legs and arms, brother and sister washed in the tin tub. While Oriano splashed around in unabashed mirth, his twin trying to scrub the both of them as fast as she could, they heard the distant drums. The procession was about to begin. They were still frantically rubbing each other’s heads when Donna Lena entered the kitchen, the baby Tato asleep in her arms. The twins froze, water still trickling from their wet hair.

Donna Lena was a robin of a woman, not small, but bent by the everyday labor she took on to make ends meet since her husband’s lack of commissions. At twenty-six her beauty was fading, her luscious hair tamed, braided flat on the nape of her neck. Fatigue was her default state. Still, as she adjusted her shawl, she couldn’t help but smile at her children.

“If you don’t have your good clothes on,” she said quietly, green-gray eyes narrowing, “by the time I finish two Hail Marys, I’ll go without you.”

Oriana and Oriano jumped out of the tub and bolted to their room.

The muddy street—surrounded on both sides by low white houses and crowned by rows of balconies—was a mass of heads swaying like sunflowers in the wind. All of Lucerìa’s craftsmen were there: carvers and tanners, smiths, farmers in their straw hats and women dressed in black, each waiting for the statue of Saint Anthony, patron saint of their contrada.

Oriana, her mother, and her two brothers stood just outside their house, watching for the approaching statue. They had already seen the lily-adorned Madonna, Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows so realistic that his wounds seemed to ooze real blood, and Santa Barbara with her golden crown and the martyr’s palm in her hands.

“Look, Harp-tooth, the Duke is farting stars!” someone shouted.

It was mad Totò, the scrawny cemetery guardian, talking to the old cat on his shoulder. A few people in the crowd tittered in response, though most ignored him. The approaching statue wasn’t exactly farting, but a pungent cloud hung over it all the same. Fireworks shot from the thin metal ring around its head. Just like the illustration on the holy card the twins had studied the night before, the statue depicted Saint Anthony’s customary halo, white beard, brown cassock, and plaster pig. Yet he was different from any other you might see in a neighboring town. He looked quite short—older, wilder—the pig at his feet vaguely misshapen as if it weren’t a pig at all.

As the statue approached, cloaked in sparkling fire and enshrouded by smoke and the beating of drums, soft hymns could be heard from the rows of women. Some were holding tallow candles, so that by their light, the statue could help them find what they had lost. But a few carried strange crowns of dried flowers, barking puppies, or squealing piglets in offering—not to Saint Anthony, but to that other one, the Emistuchivio, Duke of Under-earth and Lord of the darkness that lives below the ground.

Oriana glanced at her twin. He held his left fist behind his back, lips moving in silent prayer. Oriana took his other hand and squeezed it, hard, in warning. She was still nettled by missing last year’s spring market. She’d waited patiently for an entire year, twelve long, dreary months, and would not lose her chance once more. But as the procession approached, Oriana felt her own excitement rise. She knew Night Saints were real and allowed herself to briefly fantasize about the Duke showing himself and granting her a Boon. At least their mother had not noticed, too lost in her own reverie. Even after ten years, she missed Naples bitterly. Sometimes Oriana thought her mother would always see herself as an outsider.

“It’s almost like in Via Reale, when Don Carlos came,” Donna Lena sighed. “The whole avenue was alive with carriages and there were fireworks on the sea.”

As Oriana watched it move closer, the statue itself caught her attention, particularly the metal arch where its fireworks sparked. Oriana tugged at Donna Lena’s arm, insistent.

“Mamma? Did Papà work on the statue’s arch?”

Donna Lena shushed her, rocking the newborn in her arms, and watched as Don Giacomino—from his bay horse—reached into his bag to retrieve a handful of almond biscuits shaped like doubloons. At once, a throng of children screamed, hands shooting up to catch them. The priest laughed as he showered them with biscuits, his youthful face flushed. The children surrounded him, catching biscuits in midair or scurrying to pick them off the ground. All but one. A boy stood in front of the horse, left fist held high, offering something not to the priest, but to the statue behind him. Oriana had barely noticed her brother slip away.

“Oriano!”

Donna Lena’s scream pierced even the roar of fireworks. Yet few heard her, and none saw the wide-eyed child on the road. Certainly not Don Giacomino, proudly trotting along at a steady pace. The horse’s hooves would snap Oriano’s bones before anyone would notice.

Oriana didn’t scream, didn’t run to her brother’s aid.

Instead, she looked up at the statue.

“Please,” she whispered.

The statue tilted its head, mouth agape.

She heard a soft snap, nearly drowned out by the surrounding noise. Then the statue raised its wooden leg and kicked the first porter in the back of the head.

At once, the young man stumbled and fell.

The statue and its metal framework followed, fireworks showering the crowd. The people scattered, shrieking, as the priest reined in his frothing horse. While the women wailed at the bad omen, Donna Lena scooped up Oriano and hurried off. As the chaos dissipated, the Lucerini found their culprit in the stunned porter, a beefy apprentice of seventeen, who was seized and carried away.

Oriana wanted to shout that it wasn’t his fault. But then, whose was it? The Saint’s? The Duke’s? Or her own?

Copyright © 2025 by Giovanni De Feo

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details