Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

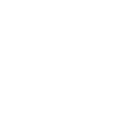

Lost Everything

| Author: | Brian Francis Slattery |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2012 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Apocalyptic/Post-Apocalyptic |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

From the author of the critically acclaimed literary SF novels Spaceman Blues and Liberation comes an incandescent and thrilling post-apocalyptic tale in the vein of 1984 or The Road.

In the not-distant-enough future, a man takes a boat trip up the Susquehanna River with his most trusted friend, intent on reuniting with his son. But the man is pursued by an army, and his own harrowing past; and the familiar American landscape has been savaged by war and climate change until it is nearly unrecognizable.

Lost Everything is a stunning novel about family and faith, what we are afraid may come to be, and how to wring hope from hopelessness.

Excerpt

The River

THEY SET THE CRATE in the belly of the boat, pointed the bow south, and floated on the thick current, under the broken arches of the bridges. Passed City Island, the flooded marina. The stadium overgrown with trees and split by shells. The baseball field now a cratered forest. Depressions filled with water from the rain, the river pushing out of the ground, flooding the roots of monumental maples. The whole place, the whole city, going under, for too much at last had been asked of it.

Reverend Bauxite looked away, then forced himself to look back. Smacked his lips and pulled a pipe from his jacket. Packed it with bits of dried apple, scraps of tobacco. He had not lit it in fifteen months. He missed the smoke, but the smell and taste of it were still there, a tang in his mouth. The feel of the bone against his teeth and tongue, and he was in his rectory again, years ago. The stained brick, the stone stairs. The dusty scent in the hallway, a hint of impending mildew. He could never figure out where it came from. In his office, blue carpeting, white linen curtains for the bay window. He was leaning against his desk, his fingers following the deep scratches in the top. Talia sat in a faded pink wingback chair, legs crossed, examining her nails. Speaking to him in a singsong voice, a lilt of minor thirds. Reverend, she said, your parishioners, myself included, think you should do more services around Lent. She was in the third row on the aisle every Sunday, fixed her eyes on him from the first word of his sermon to the last, closed her eyes when she sang. Always looked at him as if she already knew a truth that would take him years to discover.

The war was so distant from him then. Reports of small calamities from people moving north on the river. There’s been some blood down there, they’d say. A couple towns burned in Georgia, North Carolina. Outside the rectory, they were celebrating the end of the monsoon. Boys beating on boxes and trash cans. Sixteen of the people in the choir singing and clapping their hands. A small mob in the street, shaking and shuffling, just glad for the sun. The church rising behind them, straight and serene. The light falling all over the city, taking the water away. It rose in columns of steam, as if Harrisburg was on fire, but when the mist dispersed, the city was still whole. That day, it was possible to imagine it always would be. For the city was weathered and sparking, a place of chipped houses on narrow streets, and you could read on its face what it had seen. During the Civil War, it saw soldiers and munitions heading south on the trains, corpses heading north, while young men trained for more slaughter in a camp on the edge of town, parading with bayonets before rows of white tents, as if they thought the war would be orderly. During the Cold War, it got a small dose of what everyone else was so afraid of. Not an explosion, but a meltdown, emptying the streets and houses, the people thinking about giving up on the place. But they didn’t, not yet. Once, before Reverend Bauxite was born, even before the rivers rose and the trees came to swallow everything, when the last factories were not quite dead and the capital was still the capital, Pennsylvania still Pennsylvania, old men in wool jackets smoked in the bars of hotels with wrought-iron porches. On a sunny summer evening the streets teemed with people. A handsome couple rode in a red convertible with whitewall tires, a cooler of beer hanging open in the backseat. On a night of torrential rain, a slack teenager with long oily hair served Middle Eastern food to three out-of-towners, who could not keep a straight face at the things he said. Is the food any good? Because I’ve never eaten here. Here—bringing some fruit on a platter at the end of the meal—he told me to give these to you. The out-of-towners talked about him for years afterward, wrote it down in their diaries, and it fixed the city in their minds. Kept it alive for as long as they were, and after they were gone. Had the Confederate army come to Harrisburg instead of Gettysburg, had Three Mile Island been worse, Harrisburg might have died sooner, and I would not be able to tell you anything about it. It is gone now, and my memory of it, from before the war, before everything else, is all I have. If I had known when I was there that it would be gone so soon—if I had known all that was coming—I would have tried harder to remember more. To write it down then, instead of now, when I have forgotten so much.

They drifted past the islands off Steelton, under the broken span of the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Rounded the bend in the river near the blasted runway of the airport, Sunny Jim steering in the back. The destruction all seemed remote from them. Reverend Bauxite was always seeing it, the world without the war. Had to believe it would end, for all things passed, did they not, save one? On the land were burnt houses, the remains of firefights. Women kneeling in the street before a relative, bleeding away. Scorched trees, black vines, hanging over the current on the shore. Dogs in the leafy darkness at night. And in the river, fish hovered, water striders rode the surface. Herons stalked the shallows. As if the war had never begun.

Reverend Bauxite had seen it even the night Aline left. All along the Harrisburg shore, human screams and the roar of explosions. The end of the world for them, an end in fire. But all around him, mayflies rose in the air, trout leapt to catch them before their flight. He waded into the water, lifted his arms, and the flow of the Susquehanna whispered around his calves. It flowed as the bridge fell into it. Flowed as it put the fires out. We put our dead into it, our dead and mountains of slag, and still it flowed, Reverend Bauxite thought. We dug tunnels beneath it and it broke its way in, filled them, and flowed. It could wash away anything in time, without hurry or judgment, as it did before we ever saw it, as it would when we could not see anymore. But he was not consoled.

Evening was falling into night by the time they reached Three Mile Island. The river, a thin skin over the drowned causeway. Plants pulling down the rusted fence at the periphery. The road in the facility cracked by grass and saplings. A huge pine had burst through the pavement and shot for the sky, half its head knocked off by an errant shell, but still alive. The cooling towers spilled over with vines that ran in veins down their hourglass sides. Once they had been the house of the angel of death, who spread its wings over the city, getting ready to sweep everything up into it. Now they were filling with soil that trees took root in, braiding their branches together, competing for light. The cries of animals echoed inside. Keening bats, chirping birds. The hoots of small mammals. Someday, Reverend Bauxite thought, the towers would fill up all the way, the vines would cover all of them. Or the soil would be too much for the concrete to bear, and the towers would crack in two, the earth rumble out. Turn this island into a hill. He could not decide if that would be the end of us or the beginning. The glimpse of a revelation.

They lay down to sleep in the towers’ shadows, in a rusting trailer crawling with honeysuckle. A single copper cable, insulated with green plastic, jumped from a hole in the side, slithered into the river. Inside the trailer, two bunks, a big blue phone. A plastic bag with three changes of clothes. They had been moving ever since the resistance lost Harrisburg and the occupying army moved in. No more than two nights in any one place, stringing up a pirated telephone line in twenty minutes that could be taken down in ten. Floors of wet concrete, warping walls losing their plaster, spun with jagged cracks. They stared at the water damage, squinting their eyes. Played a game with each other that they used to play with Aaron. It looks like a big maple, Reverend Bauxite said. No, like a bunch of lightning bolts, said Sunny Jim. Like an old hairbrush. Like a dried-out spider. Both of them missed the boy so much, though the games brought him closer. Then Sunny Jim slept. Almost every night, Reverend Bauxite lay awake for too long after that, returning to the day his church fell. He had been outside when it happened, saw three holes appear in the tiled roof, a fourth in the wall. Heard the incoming whines of artillery a beat later. Then a bright light from within, a tremulous roar, and the church folded in on itself, became a pile of burning stone. There were forty-eight people in there, his parishioners, who had come to him for refuge. He did not know how to get them out.

When he had celebrated with his congregation before the war, their voices had multiplied on the ceiling in song. The echo when they were finished never sounded like dying, only like the sound was moving away from them, out into the world. Their voices must be moving still, Reverend Bauxite thought. Understood that believing in their persistence was a matter of faith. But he still longed to see his people, to know that they had lifted themselves from the fire. He had asked his God to grant him this, even though it meant that his faith was wavering. That he was not as strong a vessel as he wanted to be.

The toes of animals tapped on the metal roof in the dark. You should go get your boy, Jim, Reverend Bauxite wanted to say. Aline is not coming back. But Sunny Jim was asleep then, listening only for her.

* * *

REVEREND BAUXITE MET ALINE two months before the front came to Harrisburg. A meeting in the capitol building, with the mayor, several clergy, and four resistance leaders talking about what had happened in Baltimore. Horror stories. A vision of hell, Biblical violence, a village burned to nothing, people suffering an angry God’s wrath. Brother will betray brother to death, Reverend Bauxite thought, and a father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death, and you will be hated by all because of my name. But the ...

Copyright © 2012 by Brian Francis Slattery

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details