Added By: valashain

Last Updated: illegible_scribble

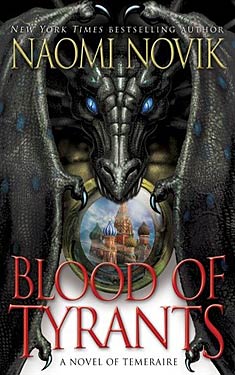

Blood of Tyrants

| Author: | Naomi Novik |

| Publisher: |

HarperCollins/Voyager, 2014 Del Rey, 2013 |

| Series: | Temeraire: Book 8 |

|

0. Golden Age and Other Stories |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Historical Fantasy Mythic Fiction (Fantasy) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Naomi Novik's beloved Temeraire series, a brilliant combination of fantasy and history that reimagines the Napoleonic wars as fought with the aid of intelligent dragons, is a twenty-first-century classic.

Shipwrecked and cast ashore in Japan with no memory of Temeraire or his own experiences as an English aviator, Laurence finds himself tangled in deadly political intrigues that threaten not only his own life but England's already precarious position in the Far East. Age-old enmities and suspicions have turned the entire region into a powder keg ready to erupt at the slightest spark – a spark that Laurence and Temeraire may unwittingly provide, leaving Britain faced with new enemies just when they most desperately need allies instead.

For to the west, another, wider conflagration looms. Napoleon has turned on his former ally, the emperor Alexander of Russia, and is even now leading the largest army the world has ever seen to add that country to his list of conquests. It is there, outside the gates of Moscow, that a reunited Laurence and Temeraire – along with some unexpected allies and old friends – will face their ultimate challenge . . . and learn whether or not there are stronger ties than memory.

Excerpt

Prologue

Arthur Hammond prided himself on a certain degree of insensibility in the cause of duty — an indifference to physical discomfort and even to social awkwardness — a squelching of the natural repugnances, when these should interfere with the progress of a diplomatic mission. Other men, blessed with a greater share of the graces, could afford delicacy: he acknowledged himself a blunter instrument, and if he must be so, he must be the ideal blunt instrument — must be seen to be as heedless of himself as of others, the only possible justification — to be thought of, if grudgingly, "Oh, Hammond — intolerable, but he will see the job through."

So he had cultivated where native tendency led, and seized without compunction or politesse whatever opportunity offered itself, with the consequence that he could while not yet thirty years of age call himself ambassador plenipotenary to China: a post which he himself had contrived to establish.

And which in turn had led him to his present miserable state, which put to bitter test his determined self-neglect: frost grimed over the surface of the woolen blankets which he had wrapped even over his head, and the hideous swoop-and-lift of the great pale-blue wings as the dragon dived to eat–at intervals too far apart to grow used to, and yet too near to recover fully from one to the other. Hunger warred with nausea at every moment; there was meat and rice in his satchel, but he scarcely managed to worm his hand out of the coverings to feed himself once a day, and half his provisions were taken off by the wind in any case. He subsisted mostly on the strong rice wine in his flask, in rationed swallows, and passed from one day to another in a daze of blurred vision — his glasses were carefully tucked inside his coat — and illness.

His figurative insensibility had become, by the end of three weeks, nearly a literal one: he did not notice for a long time when the descent at last began, and when the courier folded her wings and put her head around and said, "We have had a very pleasant flight," Hammond was unable to remove himself from the harness for half an hour together, hands shaking and clumsy.

Shen Li politely did not remark on his difficulties, but bent her head to the water-hole and drank very deeply for a long stretch; then she raised her head and shook off the water from her muzzle. "I do not see the most honorable Lung Tien Xiang," she observed, while Hammond continued to struggle with the clasps, "but you see the pavilion which he has commanded to be built, there on the mountain — "

Hammond did not see, until he had managed to wrest out his glasses and wipe the lenses, and peering saw the pavilion standing on a cliffside at the far end of the valley where Shen Li had landed. It was an ambitious edifice, something neighbor to the Parthenon in size by the columns which paced out its perimeter, as yet without a roof and circled round by makeshift huts and the columns of a yellow stone which matched the face of the cliff.

"Yes, I do; but are we not very far away?" Hammond said — or meant to say; a dry croak was all that emerged, and he gave up the attempt to converse, in favor of getting off the harness. At the moment he felt he would gladly have walked all the remaining distance in bare feet, over thorns, before going aloft again.

He let himself down from Shen Li's back in the indecorously slow manner used in China only by small children and the infirm, moving one hand or foot at a time. When he had reached the ground he sank down upon a broad smooth stone near the waterside.

"Perhaps I will go and hunt before we continue to the pavilion, if you would care to compose yourself a little," Shen Li said, a hint he could not manage to be ashamed to require. She shook out the immense wings and went aloft in a scattering of leaves and pebbles. Left behind, Hammond sat and gazed at the surface, churned-dark, and imagined drinking: the reality should have to wait another half-hour, he thought, before he might dare trust his legs to carry him across the two yards separating him from the water.

He gradually became aware, as the sun penetrated the intense chill which had settled into him, that the day was immensely hot. In Peking it was presently winter; it was as though he had been aloft for months instead of three weeks, or transported by some fairy-tale mechanism into another season. He began weakly to disentangle himself from one blanket and then another, more urgently as sweat gathered and rolled down his back, until at last he gave up all dignity and put his head and arms down and wriggled out of the rest. Abandoning his cocoon and dignity both, he simply crawled over the rock to the water and put his face into its cool relief.

He lifted it out dripping and rolled over onto his back, gasping, for once wholly aware of his body and grateful beyond measure for warmth and sated thirst, and then a pair of clawed, scaled limbs lunged flashing out from the bushes, seized upon the pile of bundling, and dragged it out of sight: he had only a glimpse of a sawtoothed maw and glittering black eyes, and then all vanished.

Hammond stared, and then leaped to his feet: his legs wavered and shook, and he fled in a shambling stumbling run, shuddering away from every branch and leaf which trembled in the wind. Horror gave him strength, and the hissed disappointment behind him: the mistake had been discovered. But he was unequal to the task; he felt a peculiar stirring beneath his feet, and he halted: a head was peering out from the bushes ahead, hungry and malicious, and there was no shelter anywhere to be seen; he was alone.

Though it evidently preferred to hunt from ambush, the creature was not unwilling to confront solitary prey; it crept one leg and then another out of the shrub-growth and came towards him at a slow deliberate pace. It had forelegs with long many-jointed talons, scaled in dark shades of brown and green, and heavy sloping shoulders. When Hammond turned to flee, there was another half-emerged from a hole up the slope a little way, watching, jaw hung open in a gruesomely eager smile, and another two heads just peering out.

His breath was loud in his ears, labored, even while terror held him for a moment immobile; then he was running, hopelessly, and crying out, "Shen Li! Shen Li!" in hiccoughed bursts as he scrambled up the one narrow rocky slope barren of growth, with the sleek bodies flowing almost leisurely in pursuit.

He heard a coughing note behind him which might have been a noise of amusement going around the creatures, and then he fell over the far side and tumbling came to rest at the feet of another man: a ragged backwoods hunter, bearded and dusty, in loose shirt and trousers and a broad-brimmed hat with, oh the blessings of Heaven, a rifle in his hand — but he was only one man, and already the five scaly heads were looking over the ridge down at the both of them.

The hunter did not pause; he raised the rifle and fired, but over the creatures' heads, and then lowering the gun said, "That is enough: be off, the lot of you; or we will clear your nest out to the bare rock."

The creatures hissed, and then as quickly, they vanished: a terrible immense shadow had fallen over them, the ground trembling. Hammond only just swallowed a shriek of dismay: there were teeth upon teeth gleaming around an endless red mouth, and an inhuman voice saying, "Oh! We ought to, anyway; how dare the bunyips, when they know very well I will not have them hunting men here."

"Temeraire," said Hammond, gulping, "that is Temeraire; it is all right," a reassurance to himself which he did not entirely believe; every nerve quivered with desire to flee.

"Hammond?" the huntsman said.

Hammond stared up at him even while taking the hand which had been offered him: a broad and callused grip, and skin tanned dark beneath the shaggy yellow beard; blue eyes; and Hammond said slowly, "Captain Laurence? Is that you?"

Copyright © 2013 by Naomi Novik

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details