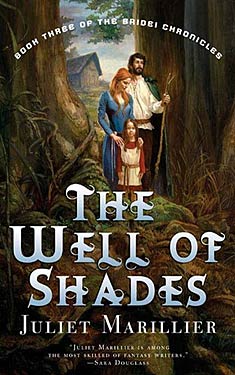

The Well of Shades

| Author: | Juliet Marillier |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2007 Pan Macmillan, 2006 |

| Series: | Bridei Chronicles: Book 3 |

|

1. The Dark Mirror |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Juliet Marillier continues the epic fantasy begun with The Dark Mirror, which Interzone called: "A fascinating evocation of life in Pictish England and an emotional roller coaster of a story."

King Bridei is a man with a mission. His wish to unite his kingdom seems almost within his grasp but there are forces working to undo his dream. He sends Faolan, his most trusted advisor (who is also a master assassin and spymaster) out into the world to ferret out the truth of who is friend and who is foe.

Along the way Faolan will uncover many truths. Some may hold the key to Bridei's future. But more important, they may unlock the secrets that Faolan has held deep within his soul for decades.

And offer him the chance of redemption.

Excerpt

Chapter One

Winter was coming. Faolan saw its touch on the land as he traveled southward out of the province of Ulaid toward a place called Cloud Hill. In the mornings the grass was crisp with frost and a shroud of mist hung low over the hills, wrapping itself around barn and stable, cottage and byre. The fields held only stubble, among which crows made leisurely paths, exchanging occasional sharp comments. The skies were uniformly gray. So long absent from his homeland, he had forgotten the rain; how it came every day without fail, gently insistent, penetrating cloak and hat and boots so a wayfarer could never be entirely dry.

He reached Cloud Hill in a fine, drenching drizzle. The tiny settlement huddled under the sudden rise of the hill, low stone huts clustered in a scattering of leafless rowans, geese gathered in the shelter of an outhouse with only half a roof, a larger hall standing square, with smoke struggling up from the thatch and a skinny gray dog skulking in the doorway. The rain became a downpour; Faolan decided it was time to put aside secrecy, and made for the entry. The dog rumbled a warning as he approached, and a man twitched aside the rough sacking that served as a door, peering out into the rain. The growl became a snarl; the man aimed a kick at the creature and it cringed back into the shadows.

"What's your business?" The tone was both surly and defensive.

"Shelter from the rain, no more."

"Not from these parts, are you?" the man muttered as Faolan came in. "Hardly a day for traveling."

There was a small crowd within, gathered around a smoky hearth, ale cups in hand. The wet was an excuse, maybe, for a brief respite from the work of smithy or field. A circle of suspicious eyes greeted Faolan as he made his way toward the fire, his cloak dripping on the earthen floor. He could not tell if this was home or drinking hall; the atmosphere was hardly convivial.

"Where are you headed?" asked the man who had let him in.

"That depends." Faolan sat down on a bench. "What's the name of this place?"

"What place are you looking for?"

He'd need to take this carefully. Deord's kin might be among these wary-looking folk, and he would not come right out with his bad news in public. "I'm seeking a man named Deord," he said. "Big fellow, broad shoulders; from over the water in Caitt territory. I'm told he has kin in a region known as Cloud Hill."

Muttering and whispers. A cup of ale was slid across the table in Faolan's direction; he took it gratefully. It had been a long day's walking.

"What's Deord to such as you?" asked a tall, thin man with calloused hands.

"Such as I?" Faolan kept his tone light. "What do you mean?"

"You've a look of someone," the first man said. "Can't quite put my finger on it."

"I've been away. Years. Deord and I share a past; we were guests in a certain place of incarceration. You'll know where I mean, perhaps. There's a name associated with it, a name folk in these parts will be familiar with."

Another silence, then, but with a new feeling to it. The cup of ale was joined by a hunk of bread and a bowl of watery soup brought in by a woman from another chamber behind. She stopped to watch him drink it.

"You and Deord, hm?" the first man said. "He's not here, hasn't been these seven years or more. Not that there aren't folk nearby would be wanting news of the man. By the Dagda's bollocks, that fellow was a fighter and a half. Built like a prize boar, and light as a dancer on his feet. When did you last see him, then? What did you say your name was?"

Faolan thought of lying and decided it would make things too difficult later. "Faolan. Yours?"

They introduced themselves. The spokesman, Brennan. The tall man, Conor. The woman, Oonagh, wife of Brennan. And others: Donal, Ultan, Aidan. Someone threw another log on the fire, and the ale jug went around again.

"I saw Deord last summer," Faolan said. "We met in Priteni lands." He was hacked apart and died in my arms. He honored a vow and was slain for it. "A good man. If he has kin in these parts, I'd welcome the chance to speak with them."

Brennan glanced at his wife. Conor exchanged looks with Ultan. The gathering was suddenly full of something unspoken.

Aidan, a lad of sixteen or so, cleared his throat. "Were you really in Breakstone?" he asked in a whisper. "And you got out, just like him?"

"Hush, lad," said Brennan. "If you'd your wits about you, you'd know men don't like to speak of such things." He addressed Faolan again. "You know Deord came back? Lasted from plowing to harvest; couldn't cope with it any longer. The time in there scars a man. Only the strongest make it out, and only the strongest of those pick up the pieces of what they had before. He came home and he left again. Where did he go? What's he doing?"

Sleeping a sleep of no dreams, and the forest creeping over to hide him. "I'd best pass my news to the family first, that's if there is one," Faolan said. "He mentioned a sister."

"You got the Breakstone mark?" someone asked in a rush. "Show us."

It was, Faolan supposed, necessary to prove he was not lying. He obliged by turning his head and lifting his hair to show the little star-shaped tattoo behind his right ear.

"Just like Deord's," said the man called Ultan. "And yet there's a look about you that suggests captors rather than captives. You mentioned a name that goes with talk of Breakstone. Your face puts me in mind of that name; an influential one."

"It's like a basket of eggs or a creel of shellfish," Faolan said smoothly. "There's good ones and bad ones. Every family has both. I was--I am a good friend of Deord's. The men who escape Breakstone Hollow are bonded for life. So, his sister? She married a local man, I understand?" He drained his cup. "This is uncommonly fine ale, Brennan."

Brennan favored him with a cautious smile. "My own brew. Deord's sister is Anda. They live around the hill in a hut on its own. We don't see much of them. Her man, Dalach, is a farrier; follows the horse fairs. He might be away. You should find someone there. It's wet out; why don't you leave it till the morning? We can find you a pallet in a corner."

"Thank you," Faolan said, taken aback that the mention of Deord and Breakstone had turned deep suspicion so quickly into welcome. "I'd best be getting on."

"The offer stands," said Brennan, glancing at his wife. "If you find you need a bed, there's one here. It's a fair walk over there. Aidan will go with you as far as the stile and point out the way."

Aidan grimaced, but went for a piece of sacking to put over head and shoulders.

"You got a knife on you?" Donal asked, offhand, as Faolan was heading out the door.

"Why do you ask?" Faolan turned a level stare at Donal, and Donal gazed at his own hands.

"What he means is, can you defend yourself?" Brennan's tone was diffident.

"I think I should be able to manage," said Faolan, who had been not only translator and spy to two kings of Fortriu, but assassin as well. "Difficult, is he, this farrier?" It was not quite a shot in the dark; he was expert at reading faces and voices, at hearing the words not spoken.

"You'd want to be on your guard," Brennan said.

The rain continued. They reached the stile and the boy pointed out the way, a muddy track barely visible in fading light and persistent downpour. His job done, Aidan fled for home. Faolan climbed over the stile and headed on, boots squelching. He had an odd sense that someone was following him. The dark forms of cattle could be discerned here and there in the gloom, but nothing could be heard but the rain and his own footsteps. Nonetheless, he looked back and looked back again. Nothing; he was being foolish, taking those men's warnings too much to heart. No self-respecting vagrant would choose such a day to lurk by the road for easy pickings. No sensible traveler would be out in such a deluge. He should have taken up the offer and stayed in the settlement overnight. All the same, the news he bore was bad, and he owed it to Deord to make sure it was his family who heard it first. He just hoped they were home; it would be a long, wet walk back.

The hut was a poor thing, a low construction of mud and wattles, with the water streaming off the thatch to pool around the base of the walls. Here and there the fabric of the place was crumbling; farrier this Dalach might be, but he was evidently not handy around the house. Someone had made an attempt at a vegetable plot; a low stone wall surrounded a dug patch in which a few cabbages grew, and a row of stakes stood ready for peas or beans. In a corner Faolan thought he saw lavender, its gray-green spikes bowing under the rain.

As he came up to the doorway, he had the eerie sense again of an unseen presence behind him. Not being a man much given to superstitious fears, he turned calmly, reaching for his knife as the gray form of the emaciated dog came into view, slinking low, ears laid back in anticipation of a blow, coat bedraggled. It had followed him all the way.

"If I had a crust on me, I'd give it to you," Faolan murmured, slipping the knife back in his belt. "But I'm all out of provisions. It wasn't worth your while." He drew a deep breath. There was a dim light inside the small dwelling; someone was home. And he had the worst kind of news to give them, news that would be hard both in the telling and the hearing. Ah, well; best get this over with.

He lifted a hand to knock on the door frame; only a strip of stained felt covered the entry. An instant later, the tines of a pitchfork were a handspan from his eyes.

"Get out, or I'll push this through your head!" snarled someone, and the thing jerked forward.

Faolan's knife was in his hand again. He calculated the position of the speaker's arms and shoulders as he replied. "I'm a friend. I mean no harm."

"Friend, huh! I know that trick. Now get out or I'll set the dogs on you!"

Faolan did not look behind him. The cur that had tailed him from the settlement was silent; if there were indeed dogs within, they did not seem to be causing it concern. "Are you Anda?" he ventured. "I'm seeking a woman of that name. I'm a friend of her brother's. I've come a long way to speak with her."

There was a silence. The dog came up to the door, stationing itself beside Faolan, ready for admittance. The pitchfork wavered.

"It is the truth. I mean no harm to anyone here. My name is Faolan."

"Never heard of you. He never said anything about you." The felt curtain moved a fraction away from the door frame, and Faolan found himself looking down into a face that was angry, scared, and much younger than he expected. Green eyes blazed defiance against grubby pale skin. He revised his guess. This was not much more than a child.

"Is your mother home?"

"Huh!"

"A reasonable question under the circumstances. It's very wet out here. We're getting soaked. Do you think you could put that thing away?"

"We're getting soaked? You and who else?" The pitchfork was back in his face. For such a small boy--girl?--the wielder was exceptionally strong.

"Me and the dog. I'd introduce you, but I don't know his name."

The curtain twitched farther. The green eyes looked down and the dog looked up, mangy tail wagging. The curtain came aside at the base, aided by a foot, and the dog slipped into the house. Faolan made to follow, and the girl--he had seen the long, unkempt hair tied back with string--spoke again. "Not you. You're a liar. Deord went away. He never came back. Why would he send you?"

Because he was dying, and could not say good-bye. "What I have to tell is for his close kin," Faolan said levelly. "When will Anda be home?"

"Soon. Any time now."

"Then might I come in and wait?"

"No. Take one step and I'll whistle for my big brothers. They'll make you wish you'd never been born. Go home. Go back where you came from."

"I do have news. She'll want to hear it."

"Go away and take your poxy news with you. If he's not coming back, he needn't think sending his friends here with messages is going to make up for it."

Faolan was thinking hard, but he could not place this girl anywhere in what he knew of Deord. The sister's child? She did not speak as a serving girl would. There was something there that curbed his tongue; he saw the longing in her eyes, for all the furious words.

"I won't hurt you," he said. "I give you my word."

"You'd be better to give me your weapons," the girl snapped.

"That's before or after you set the dogs and the brothers on me?" he queried, and instantly regretted it. Her small features tightened; there was a look on her face that sat ill in one so young, the look of a person who is accustomed to betrayal. He could not quite judge her age, but she was surely no more than thirteen or fourteen. An image of Áine came to him, and he willed it away.

"Don't you dare mock me!" the girl hissed. "I know how to use this and I'll do it. You'd better believe that. Now go. I'll tell her you came. When she gets back. Aunt Anda, I mean." Then, seeing some change in his face, "What?"

Let this not be. Let me not have to tell her now, alone, at night. "Forgive me," Faolan said, "but does that mean you are Deord's daughter?" And, before she could reply, he saw that it must indeed be so; it was in the square stance, the hard grip on the too-large weapon, the way she held her head, proudly for all the filth and the fear. Deord had never spoken of a wife, of children. Only the sister. Gods, this girl must have been the merest infant when her father went into Breakstone. She would have been five or six, perhaps, when he came home and lasted only a season. "Is your mother still living?"

"None of your business, but yes, that poxy wretch is my father and no, she's not. He broke her heart. She strung herself up from one of those oaks out there. When you go back to wherever he is, you can tell him that."

"I'm sorry," Faolan said inadequately. "Is there nobody home but you?"

"If you think I'm going to answer that, you're even stupider than you look. Go back to the settlement. I'm not letting you in." And, as he turned away, "What is this news anyway? Tell me." He heard it again in her voice, a trembling eagerness she was fighting hard to hide. His heart clenched tight. He had viewed this as the easiest of his three missions. At this moment he would have given much not to have to reply. "Go on, tell me," she said. "Just say it. He's not coming home, is he?"

Go back to Brennan's, Faolan told himself. Wait for morning. See the sister alone and tell her first, not this quivering bundle of defiance and need. You can't tell her, not here, not now.

"Tell me the truth!" she commanded, and in that moment he saw Deord's face, dying, and the strength in the lone warrior's eyes.

"It's not something I'm willing to say out here," he told her. "You need to be inside, sitting down. Here, take my knife. Hold on to that if you must have a weapon. Just put away the pitchfork. If it helps, you might notice the dog seems to trust me. Dogs are astute judges of character. Is he yours?"

She had paled at this speech; the girl wasn't stupid. Now she leaned the fork against the wall and backed into the house, holding Faolan's knife in front of her, point aimed accurately at his heart. "Sit there and don't move. Now tell me."

"You should sit down. What is your name?"

"Eile. I'll stand. Just say it, will you? What? He's not coming? Could have guessed that. He's hurt? Not much I can do about that, since he never bothered to let me know where he was..." She faltered to a halt, eyes on Faolan's face. "Just tell me. Please." She sat down abruptly, and the dog came to stand by her. It was hard to say which was the more pathetic specimen; both were disheveled and looked half-starved. The fire in the rudimentary hearth was barely alight, the wood basket near empty. Faolan could see no sign of food or drink in the place, just empty crocks on a shelf and a bucket of water.

He cleared his throat. "It's bad news, I'm afraid. I had hoped to tell your aunt first."

She waited, utterly still.

"Deord--your father--I'm afraid he's dead, Eile." Not a flicker on the neat features, not a twitch of the thin lips. "He was killed in early autumn, up in the north of Priteni lands. There was... a battle. I got there too late to save him, and he died of his wounds. I buried him in the forest. Eile, he was a good man. A brave man." No words could capture Deord's transcendent valor or his deep serenity.

Eile bowed her head a little. One hand went out to touch the dog, moving against its neck. Her fingernails were bitten to the quick, the hands raw and chapped. She said nothing.

"He asked me, when he was dying, to come here and break the news. It was a heroic end, Eile. He gave his life so that I and two friends could escape from certain death. If I say I am sorry, I don't expect you to believe it. You don't know me, and you can't know how it happened. But I am sorry; sorry at the waste of such a fine man. He loved you. I am certain of it." That part was a lie.

"That's not true." Eile spoke in a whisper. "If he'd loved us, he would have stayed. He wouldn't have just... gone."

"I don't know how much you were told about his past. Perhaps there were reasons for what he did."

Abruptly, the anger returned to the girl's eyes. "If he was going to leave, he never should have come back," she said. "It's cruel to let people think everything's going to be all right again, and then take that away. Then Mother went, too. Never mind. That's of no possible interest to you. You've told your news, you can go now."

Outside the rain was hammering down. Faolan observed three different places where drips were coming through the roof.

Seeing him looking, Eile laid the knife on the table, got up and moved automatically to set vessels beneath them. "I never did learn to mend thatch," she said shakily.

"Doesn't your uncle do that kind of thing?"

She gave a snort. "Uncle? Oh, you mean Dalach?" She spoke this name with chill distaste. "He's got other interests. Didn't you hear me? I said you can go."

"If that's what you want. I would like to speak with your aunt; tell her what I know. Perhaps in the morning." Faolan rose to his feet. "You shouldn't be alone in the house overnight."

"Why not?" Her expression was bleak, resigned. "They go away all the time. I'm used to it. I prefer it. Except when strangers come knocking, and I can deal with them."

"Yes, I'm sure you can." Faolan thought of the pitchfork. "I don't think Deord would be happy if he knew your circumstances here. I'm sure some arrangement can be made..." He had not thought this would be necessary. He had assumed Deord's sister would be comfortably settled, and that he'd need only to tell his tale and move on. But this was pitiful. Something was wrong here, surely; something more than poverty. Brennan and the other villagers had seemed good enough souls. Why had this girl been allowed to dwindle to skin and bone, a frail creature who seemed held together only by her desperate anger? The circumstances of Deord's death had meant any savings the man had were inaccessible. Faolan, however, had wealth of his own, accumulated through years of working at kings' courts. There had been little to spend his silver on. He had neither wife nor children; his parents and sisters he had never expected to see again.

"What?" Eile was staring at him. "What is it?"

"Nothing. Eile, I'm certain Deord would want some provision made for your welfare. I can discuss it with your aunt--"

"Huh! Discuss all you like, it'll never change a thing for us."

It was like holding a conversation with a stone wall. "A small amount of silver could pay a thatcher, or even someone to rebuild the whole hut," Faolan said, calculating whether he had carried sufficient funds with him. "It could provide warm clothing and fuel. It could ensure you are adequately fed."

"We do all right. Not starving, am I? I know how to provide. We don't need anyone." The look in her eyes was the bleakest he had ever seen. Her hand went down to fondle the dog's ears. For all the aggressive thrust of the chin, the defiant words, he wondered if she was waiting for him to go so she could weep alone.

"I'm sorry I brought such ill tidings," he said simply. "I can help you, if you'll let me. Deord and I both spent time as prisoners in Breakstone Hollow. Men who escape that place of captivity are bound for life to help one another. There aren't many of us. Deord took that bond to an extreme. In view of that I consider myself bound to aid his family."

"We're past aiding," Eile said flatly. "Silver won't mend us. You'd best leave me to deal with this myself. You'd be wasting your money. That's the truth."

"How old are you, Eile?"

"How old are you?" she snapped back.

"Old. I've lost count."

"I bet you haven't. Let me guess. Five and thirty?"

Gods, his sojourn in the lands of the Caitt must have taken a heavy toll. "Not quite so old as that. I'm not yet thirty. You?"

"What are you asking? Am I still a child? The answer's no. I've been old since I was twelve. That's four years now. Don't take that as an invitation. Not unless you want a knife in your belly."

Faolan was seldom shocked, but her speech startled him, and he was lost for a response.

"If you'd asked them, down at Brennan's, that's what they would have said. The girl's up there on her own, and she's no better than she should be, filthy little slut. The word's been put about so often they all believe it now, not that they come up here and try anything; when he's home they give us a wide berth, and when he isn't, I know how to see folk off."

"Believe me," Faolan said wearily, "there is no need to fear such attentions from me. That's the last thing on my mind. I've two more missions to undertake after this and they crowd all other concerns from my thoughts. Besides..." He pictured Ana by a mountain lake, wading in the shallows as the sunlight touched her hair to shining gold. Ana looking up, dazzled, not at Faolan but at the tall, bright-eyed figure of Drustan.

"Besides what?" asked Eile, crouching to put the last log on the fire.

"It could be said I've been unlucky in love." He did not want to tell that story.

"Love?" Her brows went up. "I don't think that's what Brennan and the others had in mind."

He smiled. "I've put aside the other thing, too. It makes life a great deal less complicated."

"Yes, well, you're a man." Her voice was muffled as she reached to poke the struggling fire. "When things get difficult you can put a bundle on your back and just go. That's what he did. My father. A woman can't do that. Not even with silver. Someone'd take it off her before she got as far as the next settlement. Someone'd go after her and make her come back..." Her voice trailed away. Faolan saw her take a deep, unsteady breath and square her shoulders. "I really want you to go now," she said. "I know it's wet, but I want to be by myself. Oh, drat!" The iron poker had toppled with a clang from where she had leaned it against the wall. An instant later, a small voice came from another chamber behind.

"Eile?"

"Curse it, now I've woken her up!" Eile's voice was a fierce whisper. "Go, will you?"

"Are you sure? Who is that?"

"Go. How hard is that to understand?" And, as a small figure appeared from the inner chamber, rubbing its eyes, "Now, Faolan. Before she has a chance to get scared. Hush, Saraid, it's all right. Did you have a dream?"

He went. This time, the dog did not follow. One image stayed in his head all through the decidedly uncomfortable walk back to the settlement: the child, whose age he could not guess, not being familiar with children, clad in a much-mended nightrobe, long brown hair ruffled from sleep but healthy and clean, eyes big and dark from her sudden waking. Little, certainly, and skinny like the other one, but surely well loved; he'd heard the change in Eile's voice, as if she became another girl entirely in this small one's presence. How old was Bridei's son, Derelei? Somewhere between one and two. This child was bigger, perhaps a year or so older. For her aunt and uncle to leave Eile alone in that isolated, near-derelict hut was bad enough. To leave their own small child there as well was quite unacceptable. He hadn't seen a scrap of food in the place.

Faolan sighed, pulling his wet cloak more tightly around his shoulders. He was making too much of this. It was poverty. It existed, and folk did what they could to survive. His own upbringing had been one of privilege by comparison, food on the table, a loving family, a household where smiles were common currency and the talk flowed freely. Until that day when he destroyed the very fabric of it. There had been poor people at Fiddler's Crossing; there were poor people in the settlement near Bridei's fortress at White Hill. But folk helped each other. Food was shared; a man chopped a neighbor's wood in exchange for a share of nuts harvested or shellfish gathered. His mother had taken remedies to the sick. Faolan himself had played for village festivals, long ago, before his hands turned themselves to the occupation of killing. His music had been free; rich and poor alike had shared it.

So, it was simple poverty. But Eile was Deord's daughter. Faolan was bound to help her. She'd scoffed at his silver, and he did not understand that, for it was plain she needed money. It was all he had to offer, anyway. He'd go back in the morning and give a sum to the aunt, who'd likely be less hostile. He'd request that part of it be spent on the girl's welfare: perhaps she could be taught some skill whereby she might achieve a position beyond those crumbling walls, sewing maybe. Faolan grimaced, remembering the expert grip of her small hands on the pitchfork. She'd learned that somewhere. Maybe, in his brief sojourn home, that peerless warrior Deord had begun to teach his daughter how to protect herself.

Well, tomorrow was a new day. He'd get this thing done and be on his way. Faolan had embarked from the shore of Dalriada with three missions to fulfill. In the epic poetry of his homeland, much of which he'd memorized during his bardic training long ago, things had a tendency to come in threes: three blessings, three curses, three wise sayings. The first mission, for the king of Fortriu, was to locate a certain influential cleric known as Colmcille, find out what he was up to, and carry a report back to Bridei. The second he had just attempted: to break the news of Deord's death to his kinsfolk. The third...

The third mission would carry him home; home to Fiddler's Crossing to face the unthinkable. It was years now since he had walked away from his birthplace with his harp under his arm and a bundle on his back, never to return. He had left with his brother's blood on his hands, the beloved brother he had killed in order to save the lives of his parents, his grandparents, and his three sisters. Three... Dáire, a widow at twenty, aged beyond her years; Líobhan, fourteen years old and full of defiant pride; Áine, the youngest, Áine whom his act of murder had not saved after all. He could still see her eyes, dark and terrified, as Echen Uí Néill's henchmen dragged her away. His sisters would be older now, of course, Líobhan a grown woman. He had never been able to imagine them beyond that night. Now every part of him shrank from going home. As a young man he had acted to save his family. He had not known until it was too late that, although they had lived, he had destroyed them anyway.

It would have been better to come in summer, but Bridei was astute. He had known Faolan could not secure safe passage back to Fortriu now before next spring, and still he had let him go. That meant a whole winter to be spent in Erin. A winter for three missions; that had seemed ample time. See Deord's family in Cloud Hill; investigate Colmcille in the north; confront his own past. The first had proven awkward thus far, but a few incentives should smooth the way for Eile. The second would require skills of a kind Faolan possessed in abundance, having worked as a spy and translator for two kings of Fortriu and done it expertly. The third was another matter. A lifetime would not be sufficient for him to summon the courage for it: to find out what had happened to his family since he walked away. To look in their eyes as they saw him and recognized him. He would perform that mission last. If it should chance that he ran out of time before spring opened the sea path to Fortriu once more, so be it. And if he had promised Ana, what of it? She was marrying another man, the altogether too perfect Drustan. Her way and Faolan's had parted forever. That was just as well, for she had peeled back the protective layers he had set around his heart and when it was exposed, raw and tender, she had broken it. That was entirely his own fault; Ana was a woman of honor and goodness, and all she had wanted to do was help him. When he got back to Fortriu, she would likely be gone. Who would know whether he had confronted his demons or failed to find the courage?

Up until now he'd been cautious, sleeping in barns and hedges and avoiding attention. The nearer he came to his home settlement, the more likely it was folk would know, if not his identity, at least his ties of kinship. He'd never asked to be born an Uí Néill. It was more curse than blessing. In Fortriu he had worked hard at being unobtrusive, the kind of man folk's eyes passed over. Here on his home shore his features were distinctive. It was unfortunate that the mission laid on him by Deord had happened to bring him so close to Fiddler's Crossing; more than odd that Deord, a man of Priteni blood, had kin among the Gaels here in Laigin. He'd only expected the sister; she was the only one the dying man had mentioned. Deord hadn't even given her name, just the district and the fact that she'd wed a Gael. Nothing about a daughter or a wife. He shivered, seeing again that girl's desperate eyes. The mission had proved to be a little more difficult than anticipated. Never mind that; he had silver on him, and he'd use it to make things more comfortable for Eile. Then he'd move on. North. Almost certainly north.

Copyright © 2006 by Juliet Marillier

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details