Added By: charlesdee

Last Updated: Engelbrecht

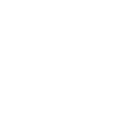

The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World

| Author: | Thomas M. Disch |

| Publisher: |

Simon & Schuster, 1998 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Non-Fiction |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

From acclaimed science fiction writer Thomas M. Disch comes "The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of", a keenly perceptive account of the impact science fiction has had on American culture. As only a consummate insider could, Disch provides a fascinating view of this world and its inhabitants, tracing science fiction's phenomenal growth into the multibillion-dollar global entertainment industry it is today. If America is a "nation of liars", as Disch asserts in this dazzling and provocative cultural history, then science fiction is the most American of literary genres. American SF writers have seen their wishes, dreams, and lies accorded the same respect as facts. From the protoscience-fiction tales of Edgar Allen Poe, to the utopian dreams and technological nightmares of European writers H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and J. G. Ballard, to American conservatives Robert Heinlein and Jerry Pournelle, liberals Joe Haldemann and Ursula le Guin, flakes William Burroughs and Philip K. Dick, and outright charlatans Ignatius Donnelly and various UFO "witnesses," Disch emphasizes science fiction's cultural role as both a lens and a medium for the very rapid changes driven by modern technology, highlighting its powers of prediction and prevarication. Much more than a history of the genre, "The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of" is an in-depth study of its ever-growing interaction with all aspects of culture-- politics, religion, and the fabric of our daily lives-- showing how it has become a cultural battlefield while helping us to adjust to new social realities, in everything from Star Trek's model of a multicultural workplace to Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative. Disch is full of high praise and trenchant criticism of the genre, but sees its darker expression in the appearance of suicidal and homicidal UFO cults that blur science-fiction-fueled fantasies with reality. Behind the spaceships and aliens Disch reveals the blueprints of the dizzying postmodern future we have already begun to inhabit.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

THE RIGHT TO LIE

America is a nation of liars, and for that reason science fiction has a special claim to be our national literature, as the art form best adapted to telling the lies we like to hear and to pretend we believe.

It has been said of Cretans that they were all liars, and we can assume, from its proscription in the Decalogue, that lying was not unknown in Mosaic times. What distinguishes American liars from those of earlier times and other nations is that the perfected American liar does not feel himself to be disgraced by his lies, even when he is caught in them. Indeed, the bolder the lie and the more brazenly imposed on the public, the more admiration the liar is accorded.

The first American hero to be celebrated for his wily ways is a folk spirit native to the continent, Coyote. Among his lineal descendants in the realm of fiction one may number Joel Chandler Harris's Br'er Rabbit, Herman Melville's Confidence Man, Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer, and Abigail Williams in Arthur Miller's The Crucible, the Puritain maiden whose lies give rise to the Salem witch trials. What sets such American tricksters apart from those of other cultures is the degree to which they solicit our admiration. I can remember my father's reading aloud the opening chapters of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and the delight we shared at the way Tom hustles his friends into whitewashing a thirty-yard-long, nine-foot-high board fence.

Before addressing the SF component of this issue, let me offer a short anthology of righteous lies from the past forty years of American history by way of suggesting the dimensions of the nation's Great White Fence. The first great lie of the post-World War II era, and the foundational whopper of the Cold War, was President Eisenhower's scout's-honor insistence, in 1960, that the U-2 shot down over the Soviet Union was not on a spying mission. That pro forma diplomatic fiction became a booby trap when the pilot, Francis Gary Powers, whom Eisenhower had presumed dead, was produced alive and stood trial for spying. Sisela Bok declares that "this lie was one of the crucial turning points in the spiraling loss of confidence by U.S. citizens in the word of their leaders."

The Vietnam War offered Americans a more extensive lesson in their government's complacent disregard for inconvenient truths. In The First Casualty, his history of war reporting, Phillip Knightley writes, concerning Vietnam:

In the early years of the American involvement, the administration misled Washington correspondents to such an extent that many an editor, unable to reconcile what his man in Saigon was reporting with what his man in Washington told him, preferred to use the official version. John Shaw, a Time correspondent in Vietnam... says, "for years the press corps in Vietnam was undermined by the White House and the Pentagon.... Yet the Pentagon Papers proved to the hilt that what the correspondents in Saigon had been sending was true.

Knightley contends that compared to earlier wars of the modern era, the press (though not the government) had a good track record for honesty. "But," he admits, "this is not saying a lot.... With a million-dollar corps of correspondents in Vietnam the war in Cambodia was kept hidden for a year."

But it was Watergate that made clear even to the most trusting and credulous of citizens that Presidents, their advisers, and anyone within distance of a bribe have as little regard for the truth as Richard III. Nixon had lied so successfully for so long about matters of such consequence that for the entire first year of the scandal, he refused to believe his robes of office would not protect him. In his steadfast denials, which he persisted in even after resigning in disgrace, he set an example of the Liarly Sublime that has never since been bettered for sheer brass.

The final establishment of lying as a right -- a right that is specifically God given -- was the work of Marine Corps paragon, presidential adviser, and 1994 Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, Oliver North. In July 1987, North had been called to testify before the Senate concerning the White House's involvement in trading arms to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages, the diversion of those illegal funds to assist (in defiance of Congress) the contras in Nicaragua, and his own perjuries with respect to these operations, which he had superintended. North's biographer, Ben Bradlee, Jr., begins his summing up of all the lies that were Oliver North's life:

Aside from North's admitted lying to Congress about the Contras, his admitted lying to the Iranians, his admitted falsifying of the Iran initiative chronology, his admitted shredding of documents and his admitted lying to various Administration officials as the Iran-Contra affair unraveled in November of 1986, there are stories, statements or claims that he has made to various people while at the NSC [National Security Council] that are either untrue strongly denied, or unconfirmable and thought to be untrue.

Bradlee recounts a round dozen of North's wilder whoppers, which include: a variety of self-promoting tales about confidences and private prayer meetings shared with the President; a tale of derring-do concerning his rescue of wounded contra soldiers (who later died, alas) as he piloted a plane through enemy machine-gun fire; his service in Angola and in Argentina during the Falklands War, and strategic tête-à-têtes with Israel Defense Minister Ariel Sharon just before the Israeli invasion of Lebanon (all three stories pure fabulation); and his dog's death by poisoning -- "presumably by those whom he said had been threatening his life." (A neighbor insisted that the dog died of cancer and old age.) The list is extensive enough to suggest that North's penchant for lying exceeded the merely strategic and expedient and amounted to pathology, and this is confirmed by the testimony of even reputed friends.

So artful was North's performance before the Senate that soon a good deal of the country had adopted the same attitude. "No one has captured the American public like Ollie North," opined a Chicago restaurateur. "Even when he's not telling the truth he's beautiful. The guy is so charming." Then columnist and future presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan lauded North as "a patriotic son of the republic who, confronted with a grave moral dilemma -- whether to betray his comrades and cause, or to deceive members of Congress -- chose the lesser of two evils, the path of honor. It was magnificent."

There must be two parties to a successful lie: the one who tells it and the one taken in. The motive of the teller is seldom difficult to discern, though it may be complex. In North's case one can scent self-advantage, a desire for applause, a certain amount of rational fear, and, not least, an inveterate delight in his own con-artistry. Surely a good deal of North's success was due to the TV audience's collusive admiration for the man's brass. Like Buchanan, they knew he was lying, but he lied so well; it was magnificent. This was the era, after all, of a President who had been caught again and again in evasions and fabulations. But people didn't care. Indeed, they applauded both men's acting skills -- the catch in the throat, the twinkle in the eye, the scout's-honor sincerity. TV critic Tom Shales favorably compared North's debut at the Senate hearings to Burt Lancaster's performance in Seven Days in May, in which Lancaster plays a general planning a military coup d'état.

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas M. Disch

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details