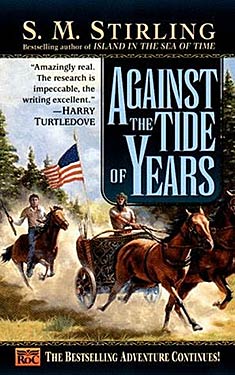

Against the Tide of Years

| Author: | S. M. Stirling |

| Publisher: |

Roc, 1999 |

| Series: | Nantucket: Book 2 |

|

1. Island in the Sea of Time |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Alternate History (SF) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Against the Tide of Years continues the adventures of the Nantucket residents who have been transported through time to the Bronze Age. In the years since their arrival, the fledging Republic of Nantucket has striven to better the primitive world in which they now exist. Their prime concerns are establishing a constitution and handling the waves of immigrants from the British Isles. But a renegade time traveler plans his own future by forging an empire for himself based on conquest by modern technology. The Republic has no alternative but to face the inevitable war brought on by one of their own....

Excerpt

Chapter 1

March, Year 8 AE

(March, 1242 BC)

"Get that God-damned moa under control!" a voice shouted from the street. It was a quarterdeck soprano, trained to carry mast-high through a gale; the accent was pure Carolina sea-island gumbo.

Marian, Jared Cofflin thought as he looked up from the papers he'd been reviewing. He joined the Councilors crowding to the windows, using his six-foot-two of lanky height to peer over their heads. One of the big birds was sprinting down Broad Street, heading for the harbor - or just away from the handlers with poles trying to catch it. People tumbled out of its way, bicycles toppled, ponies reared, a cart overset and bags of stone-ground flour burst in a beige mist.

"Damned funny-looking things, aren't they?" someone said.

Jared Cofflin agreed. And they were a lot cuter as chicks, he thought. Sort of fuzzy and about the size of a turkey; the Eagle had picked them up as eggs in a New Zealand the Polynesians had yet to reach, during her round-the-world survey voyage in the Year 2. But oh, how fast they grow. The head still looked fairly chicken-like, although it was bigger than a German Shepherd's, now; the eye bore a look of fixed stupidity leavened with terror. The bird itself stood twelve feet tall and weighed more than a cow, with a long snakey neck and bulbous body and absurd, enormous three-toed feet... pile-driver feet, and a man threw himself out of the way of a kick that could have snapped his neck. The ponies drawing another cart bolted, spilling barrels of whale-oil to break on the pavement, and the slipping, sliding chaos that followed would have been funny if it weren't so dangerous.

"In fact, it is funny," he muttered to himself.

A steam-hauler puffed out onto Broad from Easy Street pulling three wagons heaped with wood-ash and ground whale skeletons under tight-laced tarpaulins; it looked a little like an old-time locomotive, with the wheels of a heavy-hauler truck. The driver and fireman took one look and baled out the other flank of their open-sided vehicle to get out of reach of the moa's six-foot neck, but they tripped the brake and exhaust valves first and it coasted to a halt in a huge whuff of white vapor that made the giant bird flinch and slow.

Then someone vaulted onto the tarpaulins, a tall slender black woman with a long curved blade in her hands.

Marian, all right, Cofflin thought. Which explained why she wasn't here already; it took a genuine emergency to make Commodore Marian Alston-Kurlelo late for anything. For someone born in South Carolina, she had a positively Yankee attitude towards punctuality; maybe it was the twenty years she'd spent in the Coast Guard before the Event.

The katana flashed in a blurring arc as the huge bird tried to stop, turn and peck at the annoying human all at the same time. Another flash of sunlight on steel, and there was a crack sound; Alston went to one knee on the tarpaulin, and shavings of beak spun free. The moa braked frantically, leaning back and bracing its feet on the slippery asphalt, then falling on its rear with an audible thud and an ear-stunning cry of SKWAAAK!

"Get that God-damned thing under control befo' it hurts somebody, Ah said!" she shouted again.

Before it could scramble back upright the keepers were on it, and one of them clapped a bag on the end of a long pole over its head. A yank on a cord drew the bag tight, and the fight went out of the cow-sized mass of gray feathers.

"CHHHHirrrr-aaak," it sounded in muffled protest, following meekly as the keeper hauled on the cord. Two more came behind and to either side, prodding it with their poles and carefully avoiding the reflexive kicks.

"Come on, Tastes Like Chicken," the keeper said. "You've got an appointment with an axe."

"Whose bright idea was it to let one of those things loose in town?" Cofflin asked. Actually they taste more like veal, he added to himself.

Angelica Brand coughed discreetly. "Well, Chief, we're roasting a couple of them for the Event Day festivities on Main Street, and... well, it's a lot easier to get tons of bird into town if they walk, and they're usually quite docile, must have gotten away, this was just a little trouble..."

"Not if someone gets hurt or killed," he said sternly to the Councilor for Agriculture. He could hear Marian's quick firm step in the hallway outside. "Anyway, let's get back to business."

@@@

"Executive Council of the Republic of Nantucket will now come to order," the recording clerk droned. "All are present. Fourth meeting of the Year 8 After the Event, March 21st. Chief Executive Jared Cofflin presiding."

Damn, but we've gotten formal, Jared Cofflin thought, remembering the initial meetings in the first desperate scramble to survive. And single-digit years still sounded funny; granted using BC and AD was just plain silly, since nobody knew if or when - when, if you listened to Prelate Gomez of the new Ecumenical Christian Church - Jesus Christ was going to be born in this mutant history. The younger generation found the new system natural enough.

He brushed a hand over sandy blond hair even thinner on top than it had been when the Event occurred; he was fifty-six now, honest straightforward years even if he'd looped around like this. Fisherman, Navy swabby, cop, Chief of Police... and since the Event, head of state. Christ.

"OK," he said at last, when the reading of the minutes and the routine were over. "Let's get down on to the serious stuff. Martha," he went on to his wife, smiling slightly, more a movement of the eyes than the lips.

Martha Cofflin, nee Stoddard; ex-librarian, now Secretary of the Council, with a long bony Yankee face like his and graying brown hair. There were times he had trouble believing he'd got her, too.

"First item is immigration policy," she said. "Before the Council are petitions to allow increases in the yearly quota of immigrants and temporary workers to the Island from Alba." The White Isle, what this era called Britain.

Odd, Cofflin thought again. There were plenty of islands, but everyone knew what you meant when you said the Island, these days. 'Republic of Nantucket' was just plain cumbersome for ordinary conversation. I suppose it was inevitable we'd develop our own slang.

And our own feuds, he thought as hostile glances went up and down the Council table. On the one hand, Nantucket needed the hands. Everything took so much work, with the limited technology they had available; on the other hand...

Angelica Brand of Brand Farms nodded; so did half a dozen others:

"I'm trying to get sugar-beet production started, and -"

"We need that next drydock badly -"

"If we could only get some coal, there are surface deposits up in Nova Scotia -"

Our budding plutocrats, Cofflin thought. People on the Council tended to be more energetic and able than most, and to know things useful in this crazy world they'd been pitchforked into - that was why he'd picked them. Good people, mostly, but you had to watch them.

"Wait a minute!" said Lisa Gerrard of the Schools Committee, sparks crackling from her silver-white hair. "We're already overburdened - the regular classrooms too crowded - all these immigrants are illiterate, what with the adult-education classes my people are working around the clock, the teacher-training program is behind schedule, and the crime rate's up!" Thoughtful nods.

Cofflin looked at his younger cousin George, who'd taken over his old job as head of the island's police. "Ayup. Mostly Sun People. Can't hold their liquor, and then they start hitting. Or if a girl tells them to get lost, or they think someone's dissed them..."

"And besides that," Martha said, "we have to keep the numbers of immigrants reasonable - adults, especially. If we're the majority, we can assimilate them. Too many, and it'll start working the other way 'round, or we'll end up as a ruling class with a bunch of resentful aliens under us. And as George says, many of them just don't understand the concept of laws."

"Or why it's a bad idea to piss up against walls," someone laughed.

"Actually," a voice with the soft drawling accent of the Carolina tidewater cut in, "we may have something of an outlet for their aggressions."

A couple of the Councilors looked over sharply; Marian was usually extremely quiet at Council meetings, except when her defense and shipbuilding specialities came up.

"From the reports," she went on, "Walker is leavin' us no choice but another war to put him down."

Thank you, Marian, he thought, letting one eyelid droop slightly. Her imperceptible nod replied You're welcome. They'd worked together for a long time now. Played a fair bit of pool, bridge and poker together, too.

"Well, perhaps we should move on to Item Two," he said neutrally.

"Item Two," Martha said dryly, giving him a glance.

All right, all right, so I've learned to be a politician. It's a dirty job but someone has to do it.

"William Walker," she continued.

This time the expressions down the table were unanimous. Nobody liked the renegade Coast Guard officer who'd tried to carve out a God-King position for himself over in Alba. Or any of the twenty-odd other traitors with him. Nantucket had had to fight an expensive little war to stop him, and ended up with a sort of quasi-protectorate-hegemony-cum-alliance over most of southern England.

Cofflin cleared his throat and looked at the Councilor for Foreign Affairs and his Deputy; Ian Arnstein and his wife Doreen. They handed around their summary and Ian began, sounding much like the history professor he'd once been:

"Our latest intelligence reports indicate he managed to get all the way from the English Channel to Greece, arriving about three months after the end of the Alban War, and–"

There were long faces along the table when he finished; many even on the Council had hoped they'd seen the last of Walker when he fled Alba six years ago. Someone sighed and said it out loud.

"Wishful thinkin'," Alston snapped. "We should have made sure of him, no matter what it took. I said so then."

"And the Town Meeting decided otherwise," Cofflin said. The Republic was very emphatically a democracy. Back then they'd decided that the margin of survival was too thin to keep hundreds under arms combing the endless wilderness of Bronze Age Europe.

And they were basically right, Cofflin thought. Not much prospect of catching Walker, and if they'd chased him hard back then he'd have settled somewhere deep in the continental interior, where the Islanders couldn't touch him and he'd have a lifetime to brew up God-knew-what abominations. Leave him alone, and his arrogance and lust for revenge would trip him up and he'd stop within reach of salt water - planning to build a navy someday and come back for a rematch.

Marian had once said she was unsuited to Cofflin's job because she was a hammer... and saw all problems as nails. True. But she's a very good hammer, and some problems are nails, he mused, and went on aloud:

"I think we can prod the Sovereign People into some action now, though," he said; it was only half ironic. The people were sovereign here, very directly. "The screaming about how we're spending too much on defense ought to die down a little, at least."

Generally speaking he approved of the Republic's town-meeting democracy. There were times, though...

"Marian?"

Marian Alson pulled out a sheaf of papers. "Here's what I propose," she began.

Little of it was a surprise to him. Contingency planning cost nothing, and he had a limited discretionary fund to work with for more concrete preparations. At least we could lay the groundwork, since the Alban War. The new Marine regiment was coming along fairly well, from the reports - young Hollard was a doer. The time since hadn't been entirely wasted, and the Republic had grown enormously over the last eight years, in numbers and capacities.

Cofflin wondered grimly what Walker and his renegades had been doing in those same years. Walker wasn't the kind to let grass grow under his feet, damn him. If they didn't do something about him, eventually he would do something about them.

@@@

"Oh, sweet fucking Jesus Christ on a Harley," William Walker muttered in English, before dropping back into archaic Greek. "Seventy alternative meanings?"

The thick adobe walls kept the heat at bay, but light lanced in like spears of white through the small high clerstory windows. The room was a rectangle, whitewashed plaster on the walls and hard-packed earth covered in gypsum on the floor; it smelled of the damp clay in a tub, and of clay tablets drying in the wicker baskets that stood on shelves around three walls.

The Achaean scribe sat patiently on his stool. "Yes, lord," he said, humouring the newly-come stranger the High King had set him to serve. "There are seven tens of meanings for this sign."

His pen was a reed with a sharp thorn set in the tip, and his writing surface an oblong of fine moist clay pressed on a board. The thorn scratched a circle divided by two straight lines, like a four-spoked wheel.

"This is the sign ka," he said. "Also the sign for ga, kha, kai, kas, kan.."

And you have to figure out which from context, Walker thought. What an abortion of a writing system.

The real joker was that the script wasn't even well suited to Greek. The proto-Greeks - the main ancestors of these clowns - had arrived in Greece as illiterate barbarian war-bands from the north; they'd picked up writing from the Minoan Cretans, along with most of what other feeble claims to civilization they had. The original script had been designed for a completely different language; all the signs for sounds ended in a vowel, and there were a whole bunch of Greek sounds that didn't have a sign at all. The closest you could get to writing a typical word - say 'anthropos', the word for a man - was something like a-to-ro-po-se. Then they pronounced it 'anthropos', but you could hardly tell that from the script.

Pathetic. Which was all to the good, of course. Not a day went by that he didn't bless Whoever or Whatever had caused the Event.

"Thank you, Enkhelyawon," he said to the scribe. No fucking wonder nearly everyone's illiterate here. I doubt there are two hundred people who can read in the whole of Greece. "Now, how have you progressed with my people's script?"

In the original history, if 'original' meant anything here, Mycenaean civilization was going to go under in another fifty years or so in a chaos of civil war and barbarian invasion; this writing system would be completely lost, and when the Greeks became literate again after their Dark Age it would be by borrowing the ancestral alphabet from the Semites of the Levant, the Phoenicians. The Romans would get it from the Greeks, and pass their version down to Western civilization... and here he was, teaching it to the ancestors of the Greeks. More weird shit.

"Lord, a child could master that script you showed me," Enkhelyawon said tolerantly. "Twenty-six signs? That is nothing."

He picked up another slab of prepared clay and quickly wrote out the Roman alphabet. "It is interesting, lord - I have yet to find a word that cannot be written in it."

"You won't," Walker said dryly. "And it can be learned by a child - that's the whole point."

The scribe was a middle-aged man, which meant mid-thirties here, with a few streaks of gray in his pointed black beard. Walker could watch the thought percolating through, and some of the implications popping up like lightbulbs. It was a look he'd become deeply familiar with since the Event. The locals weren't necessarily stupid. He had three thousand years of jump on them, but show them a concept and they'd often grasp it PDQ, the smarter and less hidebound ones. Not all of them thought so it was in the days of our fathers and so the gods have decreed the life of man was the answer to every problem, when you showed them an alternative. The trick was finding the right ones.

Enkhelyawon looked down at the clay tablet. "And... ah, I see. The sounds of the letters seldom change."

Smart fellah, Walker thought. He'd caught stuff like the "th" sound that you needed combinations for.

"Small need for we scribes, then," the Achaean went on after a moment, his voice subdued.

"No, more need for scribes," Walker reassured him. "The more that can be written, the more will be written. And here, you write on skins as well as clay, true?"

"Of course, lord," Enkhelyawon said. "Clay is for rough notes, for monthly tallies. We transfer to parchment for lasting use; parchment is costly, of course."

Because it was a byproduct of the sheep-and-goat industry, hide scraped and pumiced until it was thin and smooth. Meat was an upper-class luxury here, and leather had a hundred other uses.

"Here is something we call paper."

"Ahh," the scribe said again, handling the sheet. "Like the Egyptian papyrus?"

"No. Notice it's more flexible. And it's made out of linen rags; this sample piece was made here in Mycenae. The skill is very simple. It can be made nearly as cheap as clay, and it's much easier to write on."

More lightbulbs went on behind the close-set brown eyes. Walker nodded and rose; one thing he'd learned in Alba, before those interfering bastards from Nantucket upset his apple-cart, was that power was like an iceberg - nine tenths of it was invisible, the unspectatcular organizational side of things. At least here he didn't have to start from absolute ground zero with a bunch of bare-arsed savages who didn't even have the concept of organization beyond family and clan.

"Think about these things, Enkhelyawon," Walker said. "I will need a man who understands both the new and old ways of writing and record-keeping. Such a man could rise high, in my service. You must speak with my vassal Edward son of John." Who had been a CPA, before the Event. Double-entry bookkeeping...

He nodded to the Achaean's bow and walked out into the main hallway of the house Agamemnon had granted him - his town house; there were estates in the countryside down by Tiryns, and the land in the vale not yet called Sparta.

This was a typical nobleman's mansion for this day-and-age. The basement storerooms and the lower course of the wall were made from big blocks of stone, neatly fitted; above that were two stories of massive adobe walls and a flat roof. The outside was whitewashed, the walls inside covered in smooth plaster and then painted with vividly-colored frescoes of fabulous beasts, war and the hunt - spotted dogs coursed a boar around this one, followed by men with spears and nets; the beams and stucco of the ceilings were painted too. In the center of the hall was a big circular hearth, sunken into the floor and stone-lined, surrounded with a coaming made of hard blue limestone blocks. Even in summer a notional fire was kept going, the smoke trickling up to a hole in the ceiling; four big wooden pillars surrounded it, running through the second story and up to a little extra roof with a clay quasi-chimney in it. A gallery surrounded the pillars with balconies where you could look down into the great hall.

It all sort of reminded him of Southwestern style, Pueblo-Spanish, like the old Governor's palace in Santa Fe but gaudier. Walker had been born and raised on a ranch in the Bitterroot country in Montana originally, but he'd been down New Mexico way as a teenager, competing in junior rodeos.

The king's palace was simply a bigger, fancier version of this, with more wings and outbuildings and a throne rather than a simple chair on the north wall. It was a little gloomy, since most of the light came through the roof or from the antechamber at one end, but his followers were already putting up oil lamps. The local olive-squeezings weren't as bright as whale oil, but the still should be operational in a couple of days. Alcohol gave a nice bright light, when you knew enough to use a woven wick and a glass chimney. Guards stood by the entranceway of bronze-bound wood, his own men from Alba. They wore equipment he'd made up there before the war, iron chainmail hauberks and conical iron helmets with nasals; they carried steel-headed spears and round shields blazoned with his device, a wolfshead.

Another came and bowed his head with his helmet tucked under one arm. His blond hair was cropped at his ears like Walker's, and he sported a close-trimmed yellow beard.

"Wehaxpothis," he said; Lord in the tongue spoken by the Iraiina tribe in remote northwestern Europe, or Chief of the Clan. "The men are settled and we are unpacking the goods. The rahax here has sent slaves, mostly women, with many loads of fine things - cloth, and furniture. The Lady Hong and the Lady Ekhnonpa your wives are directing them."

"Good, Ohotolarix," Walker said. "That's wannax Agamemnon, by the way. You and the others will have to learn Achaean, and quickly. It is needful."

It shouldn't be too difficult, either. The proto-whatever that Ohotolarix' people spoke was only about as different from this archaic Greek as French was from Italian.

"And your handfast man Bill Cuddy wishes to speak with you on the setting up of his lathes, and of Martins' forge." the young guard-captain went on.

He managed the English words well; for that matter, he could speak English of a sort. The twenty Americans among Walker's followers still used it a fair bit, though he doubted their grandchildren would. Probably there'll be a lot of loan-words. Even the civilized languages here lacked a lot of concepts.

"Let's go," Walker said, settling the katana and pistol at his belt. "We'll put in a forge, but the rest of the machinery's going down to Sparta. There's iron ore there, and we can find a millsite to put in a wheel. Oh, and get Alice."

Alice Hong was a doctor; he'd need to see to sanitation and water supply with her, here and at their other locations. Bad water was dangerous. He'd nearly crapped himself to death more than once since the Event. And she could get a start on modernizing the royal textile plant, too. The Palace had hundreds of slave-women spinning and weaving, this was a pretty centralized economy, sort of like a primitive monarchial Soviet Union. He had models and drawings for spinning jennies and kickpedal looms with flying shuttles; back in Alba they'd gotten them working well. After a lot of experiment, but it was all basic Early Industrial stuff, well within the capacities of a local carpenter. The machines would free up a lot of labor for other work and make the king properly grateful for all the extra wealth.

Hmmm, he wondered. How long before we give the King of Men the heave-ho?

Not for quite a while, he decided reluctantly. More haste, less speed. He'd have to thoroughly understand the politics here, and make some allies. It might be best to keep Agamemnon around as a front...

Walker laughed aloud and slapped his henchman on the shoulder. "Let's get to work," he said. "I want to be ready before we meet my old skipper again."

Ohotolarix was a hardy man, born to a warrior people. He still shivered slightly at the sound of his lord's laughter.

Walker's finger touched the scar Alston's katana blade had left along his face, tracing it up to the patch that covered his lost eye. Those bastards back on Nantucket won't be idle, either, he mused. Although they had a lot more than just William Walker to attend to, and it was a long way away.

Probably be a decade or so before they got around to him.

@@@

"Got it," Lieutenant Vicki Cofflin said, giving the bolt a final turn.

The new carburetor stood out against the pre-Event machining of the aircraft engine. It looked... clunkier, somehow. Really a fairly elegant solution of how to do it with nothing but mild-to-medium carbon steels, though. Just make it easy to replace, make a couple of dozen, and switch as they wear out.

She wiped her hands on a rag and then turned to Ronald Leaton. "You want to do the honors, Ron?"

The tall lanky engineer shook his head, stepping back. "It's a Coast Guard project," he said. "Seahaven's just the prime contractor. All yours, Lieutenant. Or Alex could do it; he's been a big help these last couple of months."

The younger guard officer took a step back too, blushing. Vicki nodded. "All right, then."

She took a deep breath. The converted hanger near Nantucket's little airport was always cluttered, with parts and workbenches and machine-tools. Right now it was even more so, with a big bag of goldbeater's skin - scraped whale intestine - hanging from the ceiling. A tube ran down from that to the Cessna engine mounted on a timber framework in the middle of the concrete floor. The rest of the team gathered around, in stained blue Coast Guard working coveralls or equally oil-and-grease marked ones of the unbleached gray cotton Seahaven Engineering favored. The hangar smelled of hot whale oil lubricant, and other things less familiar these days; gasoline fumes, hot metal, a faint nose-rasping hint of ozone.

Another deep breath, and she pushed the ingnition button. The engine coughed, sputtered, blatted... and then settled down to a steady roar. Some of the watchers covered their ears, unused to something Nantucket had heard little of since the days right after the Event - the drone of an internal-combustion engine at full throttle.

"Great!" Vicki shouted. The propellor wasn't mounted, but they'd rigged an output monitor; it would be a ducted-fan pusher-prop. "Let's take her up and down, and vary the mix. Stand by!"

The engine snarled, coughed again as the mixture of hydrogen from the gasbag and methanol altered. 450 horsepower, or thereabouts. About what it had put out in its first incarnation as half the engines on a Cessna puddlejumper, flying tourists in and out.

"Get that adjusted!" Vicki said. The tests continued, sweating-hot work on a summer's day.

At last she tripped the switch and wiped her hands again, smiling fondly as the engine sputtered into silence.

"Damn, you know, I think this is going to work," she said.

"No reason why it shouldn't," Leaton said. "Methanol, hydrogen, gasoline - it's all an inflammable gas by the time it reaches the piston."

Vicki chuckled indulgently; she was twenty-seven, nearly two decades younger than Leaton, and she still felt motherly about him sometimes. One reason was the otherworldly way he had of forgetting everything but the task at hand.

"I meant the whole Emancipator program, not just the engine," she said.

"Oh. Oh, yes, that too. All right people, break for lunch!"

He and Vicki and a young man in Guard fatigues walked over to a sloping table by the concrete-block wall. Plans were pinned to it. They showed a tapering teardrop shape five hundred feet long and a hundred and ten at its broadest point, with a cruciform set of fins at the rear that looked like, and were, the wings from light aircraft. Along the bottom of the forward one-third was a gondola curving down from the hull, with three engines in pods mounted along either side of it. Those looked like cut-down sections of aircraft wing too, and were.

"Never thought I'd be piloting a dirigible, of all things," she muttered to herself, feeling a rush of excitement. It would be her first command in the Guard, period, unless you counted a harbor tug. If I get it, she thought. That hadn't been decided yet.

The younger man - his name was Alex Stoddard, a fourth cousin once removed of the Chief's wife - looked up from examining the blueprints.

"If you don't mind me asking, Lieutenant Cofflin, what did you think you'd be piloting?" he said.

"F-16's," she said. "I was going to go to Colorado Springs, the year the Event happened." At his blank look, she went on: "The Air Force Academy, in Colorado. Up in the 20th."

"Oh," he nodded, polite but somehow... not indifferent. Just as if I was talking about beaming up to the Enterprise and going off to fire photon torpedoes at the Klingons. Real, but not really real.

It was amazing how much difference it made, exactly how old you'd been at the Event. Even a couple of years, and the outlook was entirely different.

I was on the cusp, she thought. Not quite an adult, but not a kid either. Alex had been sixteen on that memorable day; not a little kid, she judged, but unambiguously a kid. She'd been eighteen and raring to break out into that wider world. She'd even had dreams of the astronaut program someday. There I was, with the future all mapped out. She'd driven herself hard, especially after she'd set her sights on Colorado Springs.

But Alex Stoddard had grown up in a world where steam engines were high tech, and schooners and flintlocks everyday realities. He probably didn't get that occasional feeling of alienation, as if a glassy wall had dropped between him and the world.

Vicki ran a hand over her close-cropped reddish-brown hair and turned her attention back to the drawings. The frame of the airship was made up of two long strips that curled from bow to stern, crisscrossing each other in an endless series of elongated diamonds like a stretched-out geodesic dome. Inside that framework were a series of strengthening rings, each braced with wire like spokes reaching in to a central metal hub.

"That wire's the only metal," Leaton said, his finger tapping a horizontal view of one of the rings. "Everything else is laminated birchwood and balsa and wicker." He cleared his throat. "Only steel, rather. The clamps where the frame strips cross will have to be aluminum."

Everyone winced slightly. The Republic's new industries, here on the Island and the mainland and Alba, could turn out steel of a sort, iron, copper, bronze, brass, but aluminum had to come from pre-Event stockpiles. Leaton had a plan salted away for a small hydropower plant on the mainland to convert Jamaican bauxite; there was nothing impossible in it, apart from the fact that it would take the entire national labor force ten years to get it going, in which time they'd all starve to death. Like so much else, it would simply have to wait a generation, or two or three, while population and economic surplus grew.

"Good thing we can get the engines burning that liquid fuel-hydrogen mix," Alex said.

"Ayup," Leaton replied.

Vicki nodded; that way the reduction in lift would precisely match the lesser weight as the methanol or gasoline or whatever burned, meaning you wouldn't have to dump ballast or valve gas, which extended range. So did the middle cell of the five cylindrical gasbags shown inside the hull on the sectional view. The forward and rear two would be inflated with hydrogen, cracked out of water with a portable generator wherever the airship was based, and they'd give the airship pretty well neutral buoyancy. The middle one was a hot-air balloon. That would provide the dynamic lift, again reducing the need to dump water ballast or release precious hydrogen to rise or fall.

Leaton rested one hand on Vicki's shoulder and the other on the younger Guard officer's. "Damned fine piece of work, if I say so myself - couldn't have done it without you. It's going to work." He cleared his throat again; it was a gesture of his, like knocking on wood. "Once we've got the bugs out of it, of course."

"Of course," Vicki said dryly. Then she snorted. "Commodore Alston was... impressed... too, when she saw the plans on Monday."

"She was?" Leaton said, brightening; Alex looked eager as well. "What did she say?"

"She said..." Vicki stretched her Yankee vowels to try and match the sea-island Gullah of the Republic's military leader. "Do Jesus, ah'm glaaayd ah ain' goin' up in that-theah!"

They shared a laugh. "Got to go," Leaton said. "Washington Street Mills is having problems with their new powerloom, and if they don't get it fixed the Chief and the Commodore will flay me - they've got a big sailcloth order in for the new frigates."

The two Guard officers took their boxed ham sandwiches, hard-boiled eggs and thermos bottles of sassafrass tea to a bench outside. It was a warm day, for springtime in Nantucket - seventy-two degrees, according to the thermometer. Bright, with only a few high clouds, and the wind in from the south smelling of turned earth from the spring plowing, a rich, not unpleasant odor of fertilizer, and a tang of sea-salt under that. The airport was less overgrown and solitary than it had been last year, what with the new projects; one huge shed was going up, the frames like giant croquet hoops spanning a stretch of disused runway that furnished a ready-made floor. Besides that the scout balloon was hanging high overhead, looking like a miniature inflated version of the Emancipator's plans with a two-person gondola slung underneath, toy-tiny at the top of a thousand feet of cable.

An ultralight was going up too, wheeled out of a hanger with groundcrew hanging onto the wingtips as they wrestled it around to face into the wind. The fuselage below was a one-person plywood teardrop, with a little lawnmower-style engine and a ducted-fan propeller behind; stubby pylons extended on either side, bearing a brace of black-powder rockets.

Jesus, I hate those things, Vicki thought; she'd qualified on them, of course, and they were easy to fly, but the weapons! The electric ignition system for the rockets was... not very sophisticated, that was a nice tactful way to put it.

"You know," Alex said meditatively after a while, "I'm a little surprised that the Emancipator got approved. The Chief's usually pretty tight on priorities. I mean, it'll be useful, having something that can scout way around, and carry light cargo... and I'm damned glad I'm getting an opportunity to fly... but is it cost-effective?"

"Not here," Vicki said gently. "Not on the Island."

"Not - oh."

The younger officer nodded. Vicki Cofflin was the daughter of one of the Chief's sisters, a much closer connection than his to the Secretary of the Council. In a town Nantucket's size, some things just couldn't help leaking out along family lines.

"Well, let's get back to work," she said. "Don't you love being on the cutting edge of technical progress?"

"Damned right," Alex said, nodding.

Jesus, Vicki thought, as she followed him back into the hanger. And I thought I was joking.

Copyright © 1999 by S. M. Stirling

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details