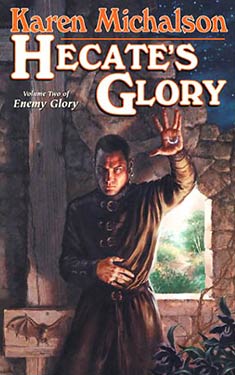

Hecate's Glory

| Author: | Karen Michalson |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2003 |

| Series: | Enemy Glory: Book 2 |

|

1. Enemy Glory |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

One heartbeat of blistering darkness to die into. One brief dying to return from.

Beginning where Enemy Glory leaves off, Hecate's Glory continues Llewelyn's strange deathbed account of his alliance with evil, the tale of his life as a highly adept priest of the goddess Hecate. Torn between his love of artistic beauty and his mandate to destroy it, Llewelyn continues to stand trial for his life. Or is it for his death?

Excerpt

One

I died before I woke, like the old prayer threatens.

I do not know how long I died. I do not know how long I lay dead and pulsing before my return. At some point in my waking it seemed that I had dreamt a good long death. Or rather, that I had died into a good long dream and found them both the same. There had been some sort of dream, for I remember my Goddess, Hecate, pulling my spirit into a questionable eternity and then my spirit making an equally questionable escape back into my body.

As I woke back into life, it seemed that my spirit had a strange downfall, that in my brief spell of dying I had risen and tripped through skies shifting storm clouds back and forth, and then that I had cut swiftly down through vanishing mountains of stars before I plopped and spread into something cold and wet. I subsided and felt like a thin dark shade flapping menace at the bottom of a dismal little pond. And then I was the pond and I knew my legs were coming soon.

I felt my thighs take shape first. They were like a distant kindhearted warmth forming itself into chaotic flesh and bone, and then they were only warm and prickly abstractions without the sensation of becoming a living body again, and then I lost them. I felt the inside of my face and eyes from somewhere in the back of my head, and then I felt my body emerge into a rough shape somewhere down below, and then I felt myself all through this new emergence for a long slow time. And then I lost all feeling again.

I lived and slept.

I think my sleep was long and purple, the still edge of a slow suspended dawn, but even there I felt or remembered something for I was sleeping now into life. I was a world away and falling, and Hecate was holding Her skirts to catch me into an eternity of bliss or damnation. But this time, before I reached Her, there were old colors in the wind that stopped my fall.

The colors told me who I was--told me how at first my spirit felt lighter than wave froth and then in spirit I was falling back into my North Country bed, and once again my body caught the weak charge of wakefulness.

First there were flimsy colors of shade which took long moments to come into yellows and browns, and then with effort I saw the old fisherman's nets and hooks hanging crazy from the ceiling above me, but their shapes blurred for a long time and I couldn't decide how far the ceiling was, or whether it was moving. I seemed to turn my head enough to hear something--a whisper of fish or a distant guess of wind still here and fading from the end of my dream. Purple sea flowers on the rough little table defined where I was and brought my long rest to rest. Their colors hurt me and so I slept in and out against them several times, lightly.

The slowly dying hurt of the colors suddenly tightened and jerked in quick painful tremors throughout my body. That is how I knew that their hurt was mine. But just as I succumbed to this new exquisite agony, the pain tore out of me and I went hollow and saw the heavy sword that Walworth, my self-appointed judge and enemy, was now holding steadily against my chest.

As I felt the unmistakable power in his magical weapon torturing me back into life, I devoutly wished that Walworth would find me guilty of the crimes he had come here to try me on, plunge his weapon through my heart, and make an end. It still wasn't clear to me why he was here, why he had found it in his interest to travel to the North Country, claim this old fisherman's hovel for Threle, and fulfill the niceties of Threlan law by listening to and scribing down the story I had spent this strange immeasurable night telling him.

What was clear to both of us was that it was a grave violation of all the laws of magic for me, a former student of Sunnashiven's Wizard School, to have entered this strange chaotic region and live to tell anybody about it.

That was Walworth's doing. The part about my still being somewhat alive, I mean. Walworth was aware that back in my youth, when I first began my formal studies in magic, my masters had placed a powerful wizard ban upon me and my fellow students against entering the North Country, so that should any of us ever do so, we would die in unimaginable agony from the slow wreck and heave of the Northern energies. He was also aware that I had come here to suffer and to die. Whether Walworth's decision to prolong my life and sickness so that I might tell my story for him to pronounce judgment upon is admirable or appalling I do not pretend to say. Perhaps it is both.

I thought ruefully of my reasons for coming to the North Country, for choosing to die here of my ban. I had not yet shared these reasons with Walworth, but Walworth had not shared with me his reasons for coming here, nor why it was so damnably important to him to keep me alive for this makeshift trial, nor explained to me how he had become King of Threle in spite of losing the war.

He had informed me, as Threlan law demands, of the crimes of which I stood accused: of high treason against his person and his people, meaning against Threle itself; of using my priestly arts to aid his enemy, Emperor Roguehan, in his attempts to conquer Threle, and to influence the critical judgment of Walworth and his generals; and finally, of causing the death of his strange, god-touched cousin, Lord Cathe.

In matters in which a verdict of guilty would bring a sentence of death, which was in all of the above matters, Threlan law allows the accused to tell the court the story of his life, no matter how long the telling, for if a life might be taken, the full context of that life must be given due consideration. I had exercised my right under law to tell my story because I had hoped that Isulde, the dark fairy who invaded and tormented both of our dreams with her wild, melancholy beauty, would come for me as she had promised, or if not, one day read of it in the court record that Walworth had been tirelessly scribing. I wanted Isulde to know and remember my life, to remember me as one among an eternity of many who loved her. That was all I cared about before dying. I knew that this improbable hovel was her North Country home. The drunken old fisherman who snored and hooted through my telling was her foster father, as obsessed with her as Walworth and I were.

I despised both of them. The hovel was a physical emblem of the old man's slothfulness, and his slothfulness reminded me that for inscrutable reasons of her own, Isulde had come to him, in one of her multitude of fairy lives, to be fostered. He was not responsible for her existence, although throughout the night he had occasionally liked to give us that impression. Unearned glory disgusted me as much as it did Walworth, but he was too well-bred to comment on it and I was too sick with the horror of my ban and of Hecate's sentence on me to bother.

I had come here not out of a sense of entitlement, but because I had hoped that Isulde would find and heal me, that her solemnly laughing fairy magic would brightly justify my decision to die. But Isulde had remained as cruelly distant as my ebbing life, as hidden as a cloud shadow vanishing under a cool clump of sea roots in the wide heat of the noon sun. I knew I was likely to die and never see or dream of her again. I knew she was likely to forget me. And I envied Walworth for the years he might have left to play with her in fairy dreams, should she continue to so choose.

Walworth kept his sword steady.

My thoughts of Isulde must have created yet another brief dying, because one of my heartbeats jerked me alive enough to once again feel the shock of knowing I was in body again and now had a physical life to hurt back into. Then I was getting rapidly used to my pulse again as Walworth put his sword aside and waited. When I woke to the energy of his sword, it was like my new pulse was bringing me somewhere and the sluggish blood rush to my head kept bobbing back down through my shoulders and neck to bring me somewhere else and so this particular return to life felt like the morning after a miserable drunk.

But I probably didn't breathe for a period of time after Walworth rushed life back into me from the sword, because I remember thinking that being alive I ought to breathe and it seems that I kept mentally preparing myself for doing so without hurrying things too much. There was a space where it seemed that I might live without breathing, or that my first new breath would commit me to my first new vulnerability and so there was strength in refusing to breathe. But air began to come and go in regular patterns and the patterns grounded me to living more securely than my freshly stinging blood and muscle.

"You have dried out your heart and tongue with speaking." Walworth said this matter-of-factly, in a voice that held neither mercy nor condemnation. Until he decided upon a verdict, he would not betray his thoughts.

I glanced dully at his sword arm and then at his hard, unrevealing eyes. "Dried and died from so much speaking. But there is much left to tell." My voice went hoarse and my words went invisible.

He glanced coolly at the snoring fisherman, who was drooling and chomping and wheezing low ugly whistle sounds. I wondered if we were both thinking of the injustice of a creature as beautiful as Isulde choosing that putrid mess of age and drunkenness as "father," of willingly coming to him in the childhood of her present incarnation to be fostered. The sources of the most exquisite beauty are laced with the most soul-killing ugliness.

Beauty knows no laws. Neither does justice.

As a priest of Hecate, and a devout votary of evil, I had a different perspective on justice than Walworth had. Hecate is evil, and insists that Her priests uphold all laws that restrain and restrict lives. Walworth, however, cherished law as an instrument of freedom, because the few laws that existed in Threle served only to augment that country's lack of restrictions. The fact that he was essentially violating a magical law by keeping me alive in order to fulfill the strict demands of Threlan justice was an interesting contradiction in his character that, were I not on my deathbed, I might have considered exploring. It surprised me, and reminded me that even back in my youth, when Walworth and I had been friends and comrades-in-arms fighting for Threle's defense, that there was much about Walworth that no one, except possibly his tutor Mirand, was privy too.

Walworth spoke decisively. "As king and judge it is within my authority to call this court to recess."

"Perhaps you will let me die during the court's recess?" I asked dully, not caring whether he thought I was making a desperate joke.

"You are free to move about, although you are obviously incapable of doing so." Walworth spoke with an odd touch of geniality in his otherwise measured voice. While I was mulling over the implications of the distinction he had just made, cloudily attempting to decide whether it was a real distinction or merely a legal one, or perhaps just an inscrutable joke on his part, he destroyed my thoughts by saying, "The medicine I made to stave off your suffering is weakening. But there is a chance that I can keep life in you awhile longer by making more and magically charging it with my sword."

I nodded weakly, embarrassed at the offer, ashamed in any way to be beholden, and not entirely sure why it was worth feeling shame.

"Then we are recessed until my return." He stood up and left the hovel.

The door let in a pitch and fall of water waves, and then it closed and softened them. A soft racket of tides pulled all my hearing and awareness into the decrepit hovel where I was and I heard the steady sigh of an old strong lake wearing down the shore outside where the scarefisher Isulde had once made still creaked and wove kelp nets out of wind.

Then I plunged into my thoughts again to consider what I had told Walworth so far under this strange court proceeding. It is not exaggeration to say he had recorded a book's worth of my telling so far. And I knew that when I was finished with telling him the remainder of my tale, which stretched before me into uncertainty like the North Country night, I suspected that he would have yet another book's worth for the court records.

I had certainly been speaking a long time. But time runs differently here in the North Country than it does in the rest of the world, and so it was impossible to say how long I had been speaking my plea, whether for hours, or days, or strange broken pieces of centuries.

I wondered whether Walworth would decide that he was obligated to execute me at my story's end. Not that it mattered, I suppose, because even if he found me innocent, I still carried that horrific ban, and so chances were better than even that my fate would be worse than death. There seemed a fair chance that my ban would destroy me before I finished speaking and Walworth rendered his verdict, anyway.

Really this was all a knave's nonsense, but here we were, and there was nothing to say to it but to speak my life for the court.

So while Walworth absented himself into the night, and the fisherman snored and hooted, I considered the salient points of the tale I had told so far.

I was born in Sunnashiven, the capital of a redundantly poor and oppressive country called Sunna that I later cheerfully abandoned for the bright improbable freedom of Threle.

My earliest betrayal came from a witch called Mother Grana, who lived next to my parents' nervously empty and emotionally crippled house. When I was still young enough to puff under flattery without the ballast of cynicism, Grana dressed me in praise andplayed exciting magical games with me, and so I loved Grana. I loved her all the more so as my birth family abused and mocked my intellectual inclinations and taught me to be ashamed of wanting to study and become a great wizard. Grana encouraged me by teaching me a wonderful and secret language, which I later learned was called Amara, a magical language known by very few wizards and spoken only by a few families in the Threlan duchy Walworth ruled before he became king. Grana also promised me magical and divine gifts that she claimed were made especially for me by the King of the Fairies and by all other manner of mythical creatures. And so I drew scintillating promises of a wonderful life from those promised gifts, but they were always blank disappointments that got "lost" or "destroyed" before she could deliver them.

One could argue I suppose that inextricably mixed with my first experience of betrayal was my first knowledge of Amara, that is, my first knowledge of something belonging to Walworth's duchy. In the map of divinity, that had to mean something, although I had no idea what.

Grana extracted a strange gift from me that has haunted me throughout my life. When I was still very young, and beginning to learn to sacrifice my true desires and longings to please Mother Grana, to destroy pieces of my young life everyday to earn her approval, she led me through a spell of terrible and sickening power. The spell resulted in her pregnancy, even though she was very old, and her pregnancy resulted in the birth of a strange child that our temple priests adopted and named Lord Cathe. It would be years before I learned that through some nearly incomprehensible twist of genealogy, Cathe was Walworth's cousin. But what I learned throughout my youth was that Lord Cathe was a "child of the gods"--that he grew and aged more rapidly than nature allowed normal humans to. And then, to end the famine that was decimating Sunna, his growth was stopped by the temple priests and he was taken prisoner to be offered as a sacrifice.

Without intending to, I became instrumental in saving his life.

Walworth would surely have to consider this as he mulled over whether I was guilty of causing Cathe's death. He would have to remember that his loyal companion, Baniff the Gnome, rescued Cathe by working an exceptionally clever bit of magical illusion that resulted in me being placed in the cell and led out to be sacrificed in Cathe's place.

And then Baniff did the decent thing and rescued me. Although he did so at the insistence of my acquaintance Lady Aleta, a young fighter who would one day rule Clio, an independent county north of Sunna that belonged to no sovereign nation. Aleta hated studying in Sunnashiven and couldn't wait to return to her homeland, but she felt obligated to me because I had come into possession of a wizard's key that seemed important to some secret cause she and Baniff were working for.

Baniff put enough value on that key to take me to Threle, where I quickly became a member of Walworth's household and privy to the secret cause that concerned Aleta and Baniff. I learned that Baniff, Walworth, Walworth's tutor Master Wizard Mirand, and Walworth's twin sister Caethne, were planning a secret defense of Threle against agents of a rival warlord, Roguehan, who was conquering an empire.

I also learned that one of these agents was my teacher from Sunnashiven's Wizard School, a particularly incompetent master wizard called Grendel, whom I later had a cheerful hand in killing. All to defend Threle, of course. Would Walworth remember that when he thought about his verdict? Would it matter that I had once killed for him?

Or would he remember that Mirand had questioned my motivation in this act? That Mirand himself had died as an indirect result of that act? Mirand of course had been brought back to life by King Thoren's wizards, Thoren having been Threle's ruler at that time. Would Walworth remember how my actions on his behalf helped to destroy the entire border town we had been living in, and all the people in it? People Walworth had sworn by whatever gods he believed in to defend? Would he believe that I suffered over that horror as much as he suffered? That I suffered at all?

About my first foray into mass destruction, unintended though it was. Anyone who cares to can read the records for the sad details. Go to the Duchy of Helas, or what was the Duchy of Helas before Walworth was given control of it, and read the scars in the land. Listen to the wind weep blood for what once lived there.

I remember riding through all the destruction as it happened, experiencing the death throes of the town in my person because I had loved that town so much. I was being led through this torture by Lord Cathe, who, to my great surprise, had made another unexpected appearance in my miserable life. Cathe tricked me into separating from my friends and taking refuge in Kursen Monastery in the Duchy of Kant, where King Thoren couldn't punish me. My friends were riding to see Thoren, to explain about the town and the danger Threle was in, and it wasn't clear whether Thoren would believe them or hold them to account for the town's destruction. Then Thoren had Walworth and his companions arrested and put on trial for treason against Threle.

While I remained at Kursen Monastery, a place devoted to training students who felt they had a calling to become priests of evil deities, I became the scribe of El, Kursen's thoroughly evil and thoroughly self-divided high priest. That is how I learned that El was involved in forging letters and paying witnesses to lie in order to make it appear that Walworth was guilty of treason. Using the wizardry Mirand had taught me, I carefully collected as much evidence as I could and managed to save my friends lives, and most likely save Threle, too, at their treason trial.

And my reward was to be consigned back to imprisonment in Kursen Monastery, in order to fulfill some bizarre detail of Threlan law. And no, Walworth, did nothing to arrange for my escape. Thoren gave him command of the Threlan army and authority to fight openly against Roguehan. I suppose he was too busy defending his country to remember the friend who saved his life.

I must admit, however, that my own leaps into friendship after that experience were not particularly noble. Every year, in the dead of winter, Kursen Monastery chose a "Sun King," a student who was designated by various solar symbols to become a petty tyrant over his fellows for the next year. As an exercise in humility, everyone was bound to obey the Sun King's slightest whim or be turned out of Kursen without record of ever having studied there. The Sun King was led outside each winter as an offering to the killing cold and left there for a day. Should he survive, he ruled for the next year.

I befriended Devon, a young boy who was the designated Sun King, by magically forcing his affections to me. I secretly made sure that he lived through each winter, and through Devon I ruled Kursen as much I could considering El kept my spirit in thrall and had absolute power over me should he choose to exercise it. Devon and I shared rooms with a splendidly incompetent advanced clerical student named Cristo whose only discernible gift was his ability to annoy everyone in Kursen, El included. And so I had my own household, which I sometimes considered a sad foil to Walworth's.

After it became clear that Walworth was willing to abandon me, I bitterly made a decision to accept evil and to study under El to become a priest of Hecate, so I might learn the ways of evil and wreak revenge on the friends who had abandoned me.

One disappointment there was especially bitter. An illusionist named Welm, one of Roguehan's spies, was briefly held prisoner in the monastery for stealing a holy relic while posing as a wine keeper. For inexplicable reasons, I desperately wanted to believe that this illusionist was Baniff, disguising himself with magic and entering Kursen with the intent of escaping with me. For a while I blessed the fortunes of war. But when I learned beyond any distortion of reason that Welm was not Baniff, I was pleased to facilitate his escape and promised to use my priestly arts to do a favor for Roguehan in exchange for one day being given a position in Roguehan's court that would allow me to wreak revenge on Walworth.

The favor asked was to create enough psychic stresses in my master, El, that he would willingly choose to damn his spirit for eternity by turning from evil to good. I was to encourage El to reject his own evil deities and to choose to suffer in eternity for betraying his calling to evil. El had his own psychic cracks and divisions. Every day of his life, whether he cared to admit it to himself or not, he violated a principle law of evil by loving his work. Evil demands self-sacrifice, but El made no such sacrifice. He liked what he did, and that was the lever I needed delicately to turn to widen this deadly contradiction in his heart.

And after I made this deal, Cathe showed up in my life with another deal. He wanted to be a god. To be immortal. And Caethne, Walworth's sister and Cathe's cousin, who Cathe claimed, improbably, was also his wife, had promised Cathe to accomplish this for him by bathing him in Walworth's blood. Although it sounded wildly out of character to me for Caethne to make such an offer, it was difficult to doubt her motivation. For as Cathe explained to me, she needed the help of a magician who was in a position to magically force Mirand to fall in with love her. She had loved him ever since he tutored her in magic, but he had not returned her passion. And because she was a student of his, he could easily defend himself against her magical advances. Of course I had once been a student of his, too, but my studies had been brief enough that any love spell I devised had a chance of working. Cathe assured me that if Mirand were to love her, Caethne would make him a god. And if he were to become a god, I would be able to inherit Walworth's duchy and wreak revenge on the whole family.

I liked it.

And so I agreed to a second deal and found myself in a position of having to fulfill my professional obligations to each side.

I also struck up a strange, quasi friendship with a traveling minstrel called Ellisand. He played brilliant, beautiful elvish music, and he occasionally gave performances at Kursen Monastery in the course of travels. The monks paid him well to make the students feel badly about themselves, especially those students who had strong musical proclivities but none of Ellisand's considerable gifts. And self-loathing is an important characteristic to encourage in many aspiring evil clerics. I loved and feared his music because it reminded me of the beauty and friendship and love that as an aspiring evil cleric I was now bound to destroy. It divided me. Fascinated me. And I felt that with Ellisand, for occasional odd moments of conversation, I could be honest.

The last thing I remember telling Walworth was how I had played a key role in destroying a military camp that was loyal to Roguehan. It was filled with Helan soldiers, Threlan ex-patriots who were angry with King Thoren for executing their former duke. So I was responsible once again, I suppose, for the deaths of a multitude of Threlans. As it was a camp posed against Walworth's army, I wondered if he would congratulate me. But as it was a camp full of Threlans, and I had used evil clerisy to destroy it, I also wondered if it would count against me.

"Strange to be so trusted. Strange to be so free and in the world once more." I had spoken these words to Walworth as a final comment on the story I had told him so far.

And then I had died briefly into the North Country night and returned at the blade of his sword.

Walworth returned through the door and gave me water to drink. It tasted like a dead star, but it opened my throat to speak.

He picked up his pen and positioned himself to resume recording my story.

I smiled. "You have taken down so much of my tale so far, my lord, that you may one day find yourself in danger of being considered a writer of tales."

He shrugged and so dismissed the implied compliment. "Flattery will have no effect on my final judgment." He said this graciously, however. The comparison clearly didn't offend him. "Do you wish to continue your plea?"

I considered. "I do not know yet, my lord."

He waited, as he had waited through my silences throughout the night. But then, so did Hecate, and eternity. Everything that mattered waited.

Copyright © 2003 by Karen Michalson

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details