Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

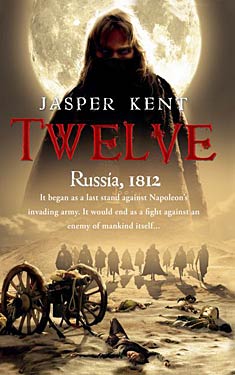

Twelve

| Author: | Jasper Kent |

| Publisher: |

Pyr, 2010 |

| Series: | The Danilov Quintet: Book 1 |

|

1. Twelve |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Historical Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The voordalak -- creature of legend, the tales of which have terrified Russian children for generations. But for Captain Aleksei Ivanovich Danilov -- a child of more enlightened times -- it is a legend that has long been forgotten. Besides, in the autumn of 1812, he faces a more tangible enemy: the Grande Armee of Napoleon Bonaparte.

City after city has fallen to the advancing French, and it now seems that only a miracle will keep them from Moscow itself. In desperation, Aleksei and his comrades enlist the help of the Oprichniki--a group of twelve mercenaries from the furthest reaches of Christian Europe, who claim that they can turn the tide of the war. It seems an idle boast, but the Russians soon discover that the Oprichniki are indeed quite capable of fulfilling their promise... and much more.

Unnerved by the fact that so few can accomplish so much, Aleksei remembers those childhood stories of the voordalak. And as he comes to understand the true, horrific nature of these twelve strangers, he wonders at the nightmare they've unleashed in their midst....

Full of historical detail, thrilling action, and heart-stopping supernatural moments, Twelve is storytelling at its most original and exciting.

Excerpt

AUTHOR'S NOTE

Distances

Averst is a Russian unit of distance, slightly greater than a kilometre.

Dates

During the nineteenth century, Russians based their dates on the old Julian Calendar, which in 1812 was twelve days behind the Gregorian Calendar used in Western Europe. All dates in the text are given in the Russian form and so, for example, the Battle of Borodino is placed on 26 August, where Western history books have it on 7 September.

PROLOGUE

A RUSSIAN FOLK TALE

Some people place this story in the town of Atkarsk, others in Volgsk, but in most versions it's Uryupin and so that is where we will keep it. All versions agree that the events occurred sometime in the early years of the reign of the great Tsar Pyetr and all agree that the town in question was infested by a plague of rats.

Rats always came to Uryupin in the summer, taking grain and bringing disease, but the people of the town, like those of any town, had learned to survive the summer months, comfortable in the knowledge that the cold of winter would kill off most of the verminous creatures--not completely wipe them out perhaps, but at least reduce their numbers so that the next summer would be no worse than the last.

But although the winters had of late been as cold as one might expect in Uryupin, they had had scant effect on the size of the rat population. The number emerging in spring seemed little fewer than there had been the previous autumn, and the number each autumn was three times what it had been in spring. By the third summer the rats were everywhere and the people of the town came up with a esperate solution. They would abandon Uryupin; leave it for the rats to feed in until there was nothing left for them to feed on. Then the rats would starve and the people, after a year or two, could return.

Before the plan could be carried out, late in July of that year, a merchant arrived in the town. He was not Russian but, as far as the people of Uryupin could tell, a European. He told the people that he had heard of their problem and that he could help. He had arrived with a simple wagon, pulled by a tired mule and covered with a great cloth, so that no one could see what was inside.

The merchant said that what he had in his wagon would kill every rat in the town and that if this did not prove to be the case he would not take a single copeck in payment. The leaders of the town asked what it was that the merchant had inside his wagon, but he would not show them until they agreed upon his price. Few in Uryupin had much appetite for the plan of abandoning the town and many had openly declared it to be madness, so the merchant needed to do little persuading before his alternative was accepted.

He dramatically (some versions of the story say ostentatiously) pulled off the cloth covering his wagon to reveal a cage; a cage containing monkeys--about a dozen of them. They had been placid in the darkness under the cloth, but as soon as the light hit them they began to scream and tear at the bars that confined them, reaching through as if to attack the onlookers who had crowded round.

The monkeys were not big, perhaps up to a man's knee, although their hunched posture made them appear smaller than if they had been standing fully upright. Their bodies, but for the palms of their hands and the soles of their feet, were covered in black fur, topped with a white ruff around the neck. Their heads were the heads of old men: fleshy, wrinkled skin, without a single hair. Some said they were more vultures than monkeys.

The merchant opened the cage and the monkeys ran out into the town. On the ground they moved on all fours with most of their weight on their hind legs, their knuckles barely grazing the earth, but soon they were using both arms and legs to climb up the sides of barns or down into cellars. Within minutes they had disappeared.

The people of the town waited. The merchant had warned them to keep their dogs and cats safe at home, since the monkeys were none too discriminating about their prey. Most kept their children at home too, reasoning that if one of these creatures could kill a full-grown dog, then why not a baby or an infant?

With no children playing and with the adults praying for success, the town might have been quiet, but such quietness as they enjoyed was continually broken by the screeching of a monkey as it found another rat. The ecstatic scream as one leapt upon its victim could cut through the town at any time of day or night, emanating from a cellar or from a loft or from behind a wall. No one saw the merchant's pets at work, but all could hear that they were working.

And soon, within a week, the people did begin to notice that there were fewer rats. The tenth day was the last on which a rat was ever sighted, foraging amongst the bins of pig feed, oblivious to the fate of its brothers and sisters; the fate that it was soon to meet.

The town's leaders were thankful. They offered the merchant what he had asked and half as much again. But the merchant refused to take anything.

"The task is not yet complete," he explained. "My friends have not yet returned and will not return until there is nothing more for them to eat."

Sure enough, though the people of Uryupin saw no more rats, they still heard the screaming of the monkeys at work, although now it seemed to come not from the cellars and the barns, but from the trees and the hedgerows. Rats are devious creatures, the people reasoned, and so no one was much surprised that the last survivors would find such unusual places to hide.

Midmorning of the fourteenth day after the monkeys had been released, the first one returned and settled down in the merchant's caged wagon to sleep. By early evening, all had returned. The merchant locked the cage, threw the cloth back over it, took his payment and left.

And the townspeople basked in the silence. For two weeks the terrifying screeching of the feasting monkeys had penetrated every corner of Uryupin and the relief at their departure, though unspoken, was shared by all. In their minds the people were glad to have got rid of the rats. In their hearts they were overjoyed to be free of the screaming monkeys.

But as the days went by, the silence began to weigh on them. At first they had thought the quietness had been so noticeable only in contrast to the noise of the past two weeks, but soon people began to realize it was actually more silent than it had been before; before the merchant and his monkeys ever arrived in the town. They could cover it up with the noise of speech and of their daily lives, but beyond that, there was nothing. It was an absolute, total silence.

And, as is often the case in these stories, it was a young boy, of about ten, who first noticed. There was silence because there was no birdsong. After the merchant's creatures had done their work, there was not a single bird left alive anywhere in the town of Uryupin.

Nor did any ever return.

PART ONE

CHAPTER I

DMITRY FETYUKOVICH SAID HE KNEW SOME PEOPLE.

"What do you mean, 'people'?" I asked. My voice sounded weary. Looking around the dimly lit room, I could see that we were all weary.

"People who can help. People who understand that there's more than one way to skin a cat. Or to kill a Frenchman."

"You're saying that we can't do the job ourselves?" My question came from instinctive patriotism, but I knew a hundred answers without having to hear Dmitry's reply.

"Well, we haven't done too well so far, have we? Bonaparte is already at Smolensk--beyond Smolensk by now probably. It's not about saving face any more. It's about saving Russia." Dmitry's voice showed his exasperation. Bonaparte had rolled across Russia as if the Russian army hadn't even been there. That was the plan of course, so we were told, but even if that were true, it was a demoralizing plan. Dmitry paused and stroked his beard, the scar on his cheek beneath reminding himof how strongly he had fought for his country; how hard we all had fought. "Besides," he continued, "there're only four of us. General Barclay's idea wasn't for us to defeat the French with our bare hands.We're supposed to work out a way to defeat them." He snorted a brief laugh as he realized he was getting above himself. "To help the rest of the army defeat them."

Dmitry's typical arrogance and his recognition of it relaxed the four of us with a ripple of silent laughter that passed around the table, but it quickly evaporated.

"You really think it's as bad as that?" It was Vadim Fyodorovich, our leader, or at least the highest-ranking of us, who asked the question.

"Don't you?" replied Dmitry.

Vadim was silent for a moment. "Yes, yes I do. I just wanted to hear it out loud."

"I wouldn't have believed it before Smolensk," I said.

"Perhaps that was the problem," said Vadim. "Perhaps none of us really believed what Bonaparte was capable of. That we do now gives us some... hope." He rubbed his face, his fingers running through his thick, black beard. "Anyway," he resumed, with a little more energy than before, "Dmitry, tell us about these people."

"A small group," explained Dmitry, "expert in working behind enemy lines. Always attacking when they are least expected. Always causing maximum disruption at minimum risk."

"They sound like Kazaki," I said.

Dmitry sucked his bottom lip, choosing his words. "Like Cossacks, yes--in many ways." He again thought carefully before speaking. "But not Russian."

"And how do you know them?" From Vadim's tone, it seemed clear that he knew the answers to his questions already. He and Dmitry had had plenty of time to talk on the grim ride from Smolensk back to Moscow. It was natural--certainly natural for Dmitry--to make sure he entered a debate with half of us already on his side.

"They helped us against the Turks." Dmitry's eyes fell on my diminished left hand as he spoke. My two missing fingers had long since rotted away in the corner of a prison cell in Silistria, severed by a Turkish blade. It was a wound that people seemed particularly sensitive about, although I had long since gotten used to it. The physical scars were the least of the horrors that the Turks had visited upon me.

"So does this mean that you know these people too, Aleksei?" asked Maksim Sergeivich, turning to me. Maksim was the youngest of the four of us. Just as I had noticed that Vadim was already on-side with Dmitry's plan, Maks was afraid that a three-to-one vote was a foregone conclusion. And that would be a big problem for Maks. He had a thing about democracy.

"No, no. This is as new to me as it is to you, Maks," I replied cautiously. I looked at Dmitry; this was all new to me, and it was odd--to say the least--that Dmitry had never mentioned it. "Dmitry and I never crossed paths in Wallachia. They seem to get about though, these... 'people.'" I stuck with Dmitry's original word. "Fighting on the Danube and then travelling all the way to Moscow to help us. Where do they call home?"

"They're from around the Danube; Wallachia, Moldavia--one of those places. They fought there from patriotism, to defend the land of their forefathers. Fighting the Turks is something of a tradition down there."

"Well, the whole thing's out of the question then, isn't it?" said Maks, his eager face lighting up at being able to point out a logical flaw. He pushed his spectacles back up his nose as he spoke. "The Danube is as far away from us as...Warsaw. Even if you sent word to them today, Napoleon would have taken Moscow and would be warming his hands by the fire in Petersburg before they..."

Maks stopped before he finished his sentence. He was, more than any man I knew, able to detach himself from his own world. Most of us would find it hard to describe so glibly the realization of the horror we were all fighting, but Maks could conceive the inconceivable. It was a useful and at the same time sometimes frightening trait. But today, even he understood the potential reality of what he had said.

Vadim bridled at the image. "If Bonaparte were to make it to Moscow or Petersburg, then the only fires he would find would be the smouldering remains of a city destroyed by its own people rather than allowed to fall into the hands of the invader."

At the time it sounded like tub-thumping bravado. We little knew how true his words would turn out to be.

"Maks does have a point though," I said. "The whole thing is academic now. If we were going to use them, we should have sent word a long time ago."

"Which is why I did," said Dmitry.

He looked round the room, into each of our eyes in turn, daring one of us to object. Vadim already knew. Maks saw no logical argument against a fait accompli. I was tired.

"There was a letter from them waiting for me when we got back here today," continued Dmitry. "They've already set off. They expect to be here by the middle of the month."

"Let's just hope they don't get caught up in the French lines along the way." My comment sounded cynical, but it was a serious issue. Half of the Russian army had been dashing back from a rushed peace settlement with the Turks and had only just made it ahead of Bonaparte. Dmitry's friends would be running the same risk. But none of the others cared to take up the point, so I let it lie.

"How many of them are there?" asked Maks.

"That depends," said Dmitry. "Twenty if we're lucky--probably fewer."

"Well, what use is that?" I asked. I sounded more contemptuous than I had intended to, but no more than I felt.

"Davidov performs miracles with just a few Cossacks," Vadim pointed out. It was below the belt; Denis Vasilyevich Davidov was something of a hero of mine. But the comparison was unfair.

"A squad from a Cossack voisko consists of eighty men or more; not twenty. Are your friends worth four Cossacks each?"

Dmitry looked me square in the eye. "No," he said. "They're worth ten." I felt the sudden urge to punch him, but I knew it was not Dmitry that I was angry with.

"Perhaps you should tell us what makes them so remarkable," said Vadim.

"It's hard to describe," said Dmitry, considering for a moment. "You've heard of the Oprichniki?"

Vadim and I both nodded agreement, but Maks, surprisingly, had not come across the term.

"During the reign of Ivan the Fourth--the Terrible, as he liked to be called--during one of his less benevolent phases, he set up a sort of personal troop of bodyguards known as the Oprichniki," explained Dmitry. "The job of the Oprichniki was internal suppression, which is obviously not what we're talking about here, but the method of an Oprichnik was to use absolute, unrestrained violence. Officially, they were monks. They rode around the country wearing black cowls, killing anyone that Ivan deemed should die. Although they were monks, they weren't educated, but their faith gave them the fanaticism that Ivan needed."

"And these are the guys that are going to help us?" asked Maks dubiously.

Dmitry nodded slowly. "There are similarities. My friends understand that violence is of itself a weapon. They are unhindered by scruple or fear."

"And are they religious?" I asked. "Monks, like the original Oprichniki?"

"They're not monks"--Dmitry paused, as if considering how much to tell us, then continued--"but they have their own fanaticism. Where they come from, on the borders of the Ottoman world, Christianity has always been an adaptable concept."

"Are they controllable? Trustworthy?" asked Vadim.

"As trustworthy and controllable as a musket or a cannon--in the correct hands. They just need pointing in the right direction and they get on with it."

"And you're sure they don't expect payment?" Vadim's question clearly referred to a conversation he and Dmitry had had in private.

"They enjoy their work. Like any army, they live off the vanquished." None of us quite followed Dmitry's meaning. "The spoils of war. Armies live off the gold and the food and whatever other plunder they take from the enemy."

"I'm not sure they'll find enough gold with the French army to make their journey worthwhile," I said.

"There are rewards other than gold," said Dmitry with an uncharacteristic lack of materialism. "They are experts at taking what the rest of us would ignore."

I don't think that any of us really liked the idea of resurrecting the Oprichniki, but the name stuck, even though we never said it to their faces. Once we'd met them, we got some sense of how Dmitry came up with the analogy.

It was late and Vadim Fyodorovich brought the meeting to a close. "Well then, gentlemen, we have a week or so in which to prepare for the arrival of the 'Oprichniki.' That gives us plenty enough time to work out how to make best use of them." He took a deep breath. He looked exhausted, but tried his best to instil some enthusiasm into all of us. "It's been a tough campaign so far, I know, but this time I really feel it in my water that Bonaparte has overreached himself and that we've turned the corner. Eh? Eh?"

He seemed, against all hope and experience, to expect some sort of rousing cheer of agreement, but he got little more than a nod or a raised eyebrow as we each left the room and headed for our beds. He was not the kind of man to whom stirring propagandist speeches came naturally, nor were we the kind to be stirred by them. That's part of what had made us, until then, such a good team.

We had ridden at almost full gallop from Smolensk to Moscow, sleeping rough when we could find no convenient lodgings. The weather of early August was oppressively hot for some, but I enjoyed it; I always loved the summer and hated the winter. Even so, it was good to sleep in a real bed again. It was the same bed I always slept in--usually slept in--when staying in Moscow, in an inn just north of the Kremlin, in Tverskaya; the same inn where we had held our meeting. It was the small hours by the time we broke up, but I did not fall asleep immediately. Instead, my mind drifted back to another meeting, the first time I had met Vadim, the time when our strange little group had first begun to assemble.

"Dmitry Fetyukovich has told you what this is all about?" Vadim had asked.

Dmitry Fetyukovich, as ever, had not told me much. It had been seven years before, November of 1805; less than a month before the Battle of Austerlitz. Dmitry had said he knew of a major who was trying to form a small band for "irregular operations." I'd been interested and so the meeting had been arranged. I'd never spoken to Vadim, but I'd seen him around the camp, usually slightly dishevelled and unmilitary, but always respected by those who knew him.

"Not entirely, sir," I had replied. "Dmitry just told me it was something a bit out of the ordinary. It sounded worth a go."

"There's no 'sir's here," Vadim had told me, firmly. In those days he had been a little more austere than he became as I got to know him better, and as he became better practised at getting his way without coercion. "Respect for your superiors may be the great strength of the Russian army, but it doesn't always encourage..." He could not find the word.

"Thinking?" suggested Dmitry.

"Exactly," Vadim had continued. "Thinking in the army can get you into a lot of trouble."

He and Dmitry exchanged a smirk. Dmitry later told me that Vadim had once almost been court-martialled for disobeying an order. In doing so he'd captured an enemy gun emplacement and turned the tide of a battle, but the order had come from a very rich, very noble, very stupid senior officer and there were many who thought that the sensibilities of that breed of officer were of far greater significance than the winning of mere battles. Fortunately, others didn't. Moreover, and although none would have guessed it from his manner or demeanour, Vadim was also very rich and very noble, with the added advantage of not being in the slightest bit stupid. He had been promoted to major and given a pretty free rein to do whatever he thought would best harass the enemy.

"And thinking," Vadim went on, "is what I'm told you do rather a lot of."

I smiled. "It's more of a hobby, really. Like you say, there's not much use for it in battle."

"Not in battle, no. In battles you obey orders--generally. When I give orders, you obey orders; but that won't happen often. And don't imagine you'll avoid battles either. You'll still have to fight like a soldier. It's what we do between the battles that will be different."

"And what will we be doing?" I asked.

"Espionage. Sabotage. Uncovering information and spreading chaos. Sometimes in a small group, sometimes alone. I'll tell you what to do, then we work out how to do it. How's your French?"

Unusually, we had been speaking in Russian--something that was becoming popular amongst those who wanted to prove themselves true patriots.

"Pretty good," I said.

"Dmitry tells me you could pass yourself off on a street in Paris."

"I suppose that's true," I ventured.

"Well, if it's true, then say it. Modesty is just another form of lying; useful with the ladies but dangerous amongst brothers-in-arms. You tell someone you're only a 'pretty good' shot then he'll start taking risks to cover for you. Then he gets killed and it turns out you're a damned good shot, and his death's down to you. What are you like as a shot?"

"Pretty good," I replied. Vadim frowned. "But I'm damned good with a sword."

Vadim grinned. "Good. Ideally, you won't need to spend too much time using either. One last thing--for now: can you recommend anyone else for this? We can work as a team of three, but four or five would be better."

"Another thinker, you mean?" I asked.

Vadim nodded. I thought for a moment, then turned to Dmitry. "Have you mentioned Maksim Sergeivich?"

"I thought about him," said Dmitry. "He's very young and he's a bit... odd."

"He certainly thinks," I said.

"That's just it," replied Dmitry. "He thinks odd things."

"Sounds ideal," announced Vadim.

And so the following day Vadim had been introduced to Maks. He had required even less persuasion than I had, but then it would have been hard to find a role that was more appropriate for him. We had all met for the first time within the space of just a few months, but already our band was complete.

But now, seven years later, Dmitry had invited new members to join us--men that only he knew and only he could vouch for. Desperate diseases call for desperate remedies, but as I fell asleep I couldn't help but feel uncomfortable about these Oprichniki that Dmitry was to introduce into our midst.

Despite our late night, I woke early the following morning. We had a week until Dmitry's "people"--the Oprichniki--arrived and, with only a little preparation to be made for them, that meant almost seven days of leisure.

I walked around the still-familiar streets for the first time in nearly six months and noticed little had changed except the weather, and on this glorious summer's day that was a change for the better. The people were much as they had been. Certainly they knew that Bonaparte was approaching, but they knew too that he must stop. No emperor whose throne was as far away as Paris could ever march his army all the way to Moscow. The fact that he had marched as far as Vilna, as Vitebsk, as Smolensk, the fact that those cities were also unassailable from Paris, they fully understood. But that didn't change their belief that Moscow itself could not be reached. And I was in full agreement. Of everything I was to see in that long autumn of 1812, despite the almost unimaginable horrors, the most unreal was to be the sight of French troops on the streets of Moscow.

Was it just that it wasn't my home town that made me love Moscow? I'd lived in and around Petersburg my whole life. It was beautiful and comfortable and familiar. Familiarity didn't breed contempt, simply predictability. A knowledge of every inch led to few surprises. It was odd then that Petersburg was by far the younger of the two cities. It had been only a century before--precisely a century, in 1712--that Petersburg had replaced Moscow as the capital city, less than a decade after its foundation.

A city built as quickly as Petersburg, and built to the plans of so forceful a character as Tsar Pyetr, appeared to me to be precisely what it was--synthetic. Moscow was created over centuries by people who built what they needed to live. Petersburg was built to emulate the great cities of Europe, and so it would always seem counterfeit--only slightly more real than the cardboard frontages of the villages erected by Potemkin to give Tsarina Yekaterina a more picturesque view as she toured the backwaters of her empire. But Petersburg was the capital, and society adored it. Society had moved to Petersburg, but life remained in Moscow.

My wife, Marfa Mihailovna, loved Petersburg in a way I never could. She was just as familiar with it and used that intimacy as the basis for seeing a depth that I could never perceive. Our young son seemed to love it too, but at five years old, nothing was yet familiar to him; everything was a new adventure. So Marfa stayed in Petersburg and, however far I travelled, returning to one meant returning to the other. Returning to either or to both felt the same--comfortable.

As I meandered through the Moscow streets, I drank in each of the great sights of the city. I walked along the embankment of the river Moskva, looking up at the towers that punctuated the walls of the Kremlin. I turned north, passing beneath the lofty onion domes of Saint Vasily's and then across Red Square, thronged with Muscovites going about their lives. Then I continued northward, back into the maze of tiny streets in Tverskaya.

But perhaps I was fooling myself. Perhaps I was wandering around the streets of Moscow, marvelling at its people and its buildings, in order only to tease myself before I headed for my true destination, like a man who eats all his vegetables first, praising their subtle flavour while really trying to leave his plate empty of everything but the steak that is the only part of the meal he ever wanted. Or was I like a drunk who wakes early and realizes that there are times when it is too early in the day even for him and so kills time, trying to keep his mind off that first sharp, sweet drink?

It was almost midday when I reached the corner of Degtyarny Lane and sat down again on the bench where I'd first sat the previous December.

Back in the winter of 1811, I'd been there with Dmitry and Maks. Vadim had been home in Petersburg for his daughter's wedding. I'd been at the wedding too, but had returned to Moscow almost straight after, countering my guilt at the look on Marfa's face with the strange anticipation that something would happen, had to happen, once I got back to a city as vibrant as the old capital.

But little had seemed to be going on and so the three of us had, before long and for whatever reason, found ourselves sitting on that bench in the quiet, snow-covered square exchanging jokes and watching the men (and occasional women) entering and leaving the building opposite.

There had been a moment of silence as our eyes were all taken by a particularly fine-looking young lady who was leaving the building, a silence which Maks filled with an announcement made in the voice he usually reserved for describing the political affairs of nations.

"It's a brothel!"

"Of course it's a brothel," laughed Dmitry. To be honest, I hadn't noticed, but thinking about it, it seemed pretty obvious. Dmitry may have been bluffing too, but it always seemed best to appear worldly-wise in front of a young soldier like Maksim, so I laughed along with Dmitry.

"You want to go in?" Dmitry asked Maks. "It looks like it's something of a military establishment." And indeed most of the clientele did seem to be cavalry officers, just like ourselves.

"No thanks," Maks had replied, in a voice that made me wonder whether he had any human desires at all.

Dmitry turned to me. "Aleksei? Ah no. You've got the loving wife and family."

"How about you?" I asked Dmitry.

"Me? No. I don't like to play the field either." He winked at no one in particular. "There's a little place I use on the other side of Nikitskiy Street. Cheap and clean. I'll stick with that."

The girl who had caught our attention earlier soon returned, clutching tight to her body the basket of fruit and other foods she had gone out to buy. She was astonishing. Her large eyes sloped slightly upwards away from her nose and her rich lips were pressed tightly shut against the wind-blown snow through which she struggled.

I felt I had seen her before. Suddenly, it dawned on me.

"She looks like Marie-Louise."

"Who?" snorted Dmitry.

"The new empress of France," explained Maks.

"The new Madame Bonaparte," was my description.

"Ah! The old Austrian whore," was Dmitry's.

All of our comments were to a reasonable degree true. In 1810, Bonaparte had divorced his first wife, Josephine, and wedMarie-Louise, the daughter of the Austrian emperor, Francis the Second. Josephine had been unable to provide Bonaparte with children and the emperor needed an heir. How quickly the French had forgotten what they did to their last Austrian queen.

"She looks a bit like her, but not much," said Maks.

"Who knows?" I replied. "I've only ever seen one picture, but they are similar."

The picture I had seen enchanted me. It was just a print based on a portrait of her, but she seemed to me truly beautiful--much better than Josephine. But then, they said Bonaparte loved Josephine. That's why they had stayed together even without children.

"Better have him bed some Austrian harlot than touch the tsar's sister," said Dmitry. "She was too young. Very wise of Tsar Aleksandr to tell Napoleon to wait until she was eighteen."

Dmitry raised his arm. I looked up and noticed that he had made a snowball, which he was preparing to throw at the girl as she trudged her way back to the door of the brothel. However minor it was, it seemed so needlessly cruel that I shoved at his arm with my own as he threw. He was an excellent shot and, even with my hindrance, the snowball hit the wall just inches in front of her face.

She glanced towards us and, because my arm was raised, assumed that I had been the thrower. The look she gave had such a combination of anger and pride, of asking why I presumed to treat her in such a way, that I felt almost compelled to go and apologize, not just to tell her that it hadn't been me, but to explain why I hadn't tried harder to prevent it, to be forgiven for even knowing the man who had thrown the snowball.

Dmitry chuckled to himself. "Did you hear what she said to him on their wedding night?"

"Who?" I asked.

"Marie-Louise. To Bonaparte," replied Dmitry, revealing a greater knowledge of French royal marriages than he had previously shown. "After he'd screwed her for the first time, she liked it so much she said, 'Do it again.'"

I joined in Dmitry's raucous laughter, even though I'd heard the story before. Maksim didn't laugh. At the time, I'd presumed that he simply didn't get it.

"You know what she'd say?" continued Dmitry through his laughter, indicating the young "lady" whose resemblance to Marie-Louise had started the whole conversation. "She'd say 'Do it again--second time is half price.'"

This time both Dmitry and Maks laughed, but I didn't. It's one thing to insult a French empress, another to insult a Russian whore.

As it turned out, she charged by the hour.

Copyright © 2010 by Jasper Kent

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details