Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

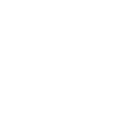

The Silver Ship and the Sea

| Author: | Brenda Cooper |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2007 |

| Series: | The Silver Ship: Book 1 |

|

1. The Silver Ship and the Sea |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Colonization Space Opera Human Development |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The colony planet Fremont is joyous, riotous, and very wild. Its grasses can cut your arms and legs to ribbons, the rinds of its precious fruit can skewer your thumbs, and some of the predators are bigger than humans. Meteors fall from the sky and volcanoes erupt. Fremont is verdant, rich, beautiful, and dangerous.

Fremont's single town, Artistos, perches on a cliff below rugged mountains. Below Artistos lie the Grass Plains, which lead down to the sea. And in the middle of the Grass Plains, a single silver spaceship lies quiet and motionless. The seasons do not dull it, nor do the winds scratch it--and the fearful citizens of Artistos won't go near it.

Chelo Lee, her brother Joseph, and four other young children have been abandoned on the colony planet. Unfortunate events have left them orphaned in a human colony that abhors genetic engineering--and these six young people are genetically enhanced.

With no one to turn to, Chelo and the others must now learn how to use their distinct skills to make this unwelcome planet home, or find a way off it. They have few tools--an old crazy woman who wonders the edges of town, spouting out cryptic messages; their appreciation and affection for each other; a good dose of curiosity; and that abandoned silver space ship that sits locked and alone in the middle of the vast grass plain...

Excerpt

Chapter One: Our Second Loss

Let me start with a nearly perfect dawn on Fremont. Morning light dappled my legs with patterns made by the broad leaves of the tent tree I sat beneath. The Lace River ran smoothly fifteen meters below me. Two of our seven moons shone above me: Faith, large and round, followed by her smaller companion, Hope; both pale in the bright daylight. As round as the moons, but near at hand and small, the redberry bush fruit had swollen into sticky orbs the size of my thumbnail. My fingers were stained red. I sat, twirling a stick idly in my hands, thinking about the summer, which had been easier than most, about the good harvest being tucked into the granaries and the storage bins. My hands moved of their own accord, restless because the peace made me restless.

Footsteps on the path behind me announced my little brother Joseph, just old enough for light fuzzy down to ghost along his chin and a slight widening of the shoulders to emphasize his thin frame. He grinned widely as he sat down next to me, and then took the stick from my hands.

“Here, Chelo, let me show you.” He reached up and plucked a wide green diamond-shaped leaf from a low branch of the tent tree. He folded the leaf, then made a crack in the top of the dry stick and wedged the leaf into the crack. “See?” He twisted the stick, fast, so the black mottling of the whitish bark blurred to gray, his palms flat. He smiled, impish, his dark eyes dancing. His hands flew open and the stick rose, impossibly, higher than our heads, whirring like night-crickets. Leaf and stick separated. The leaf fluttered down onto my head and I laughed with him.

“Come on, sis, let’s go.” He stood, shifting on his feet, full of restless energy. He was nearly my height, black-haired and black-eyed like me, and fast and strong, like all six of us altered. In Joseph, speed and strength showed in long wiry limbs and well-defined muscles. Neither he nor I displayed obvious physical differences; we didn’t have Bryan’s size or Kayleen’s long feet and extra strong toes.

Green Valley spread below us as I followed Joseph down the packed-dirt path to the science guild hall. Artistos nestled against the Lace Forest. The Lace River, behind us now as we walked, bordered Artistos to the north, cliffs marched up and away to the east, cleared land gave way to thick forest to the south. Another cliff face bounded the valley, falling westward to the Grass Plains that themselves ended in the sea. The town itself spread neatly out from the largest open space, Commons Park, and thin strips of green parkway ran beside the river, buffering Artistos and making space for fishing and gathering and walking. The two cliffs, up and down, the High Road and the sea road, forced the town’s small industrial base north, across the river, and barns and fields bellied up to wide tent trees and tall thick-trunked near-elm of the forest in the south. Dense thorny underbrush made the forest a true barrier. All the land we needed so far had been long cleared, although each spring we fought the forest to maintain the boundary.

Nearly everyone lived as close to Commons Park and the guild halls as they could, so the edges of Artistos were empty. Still, Joseph and I passed small groups of people hurrying to cross the river and start work.

We began to walk faster. If we were last, Nava would be mad. We already angered her just by being ourselves, by being born at all. We couldn’t help that, but we could be on time. Our jobs were simple. For us. Joseph would slip open to the data nets, feeling the subtle messages carried on the air from the networks; his blood, bone, and then brain vibrating with and understanding the myriad stories of hundreds of pinpoint wireless data nodes that surround Artistos. Today, he would monitor a repair team heading past the perimeter to fix and replace failing network nodes. Meshed with satellite data and images from Traveler, Artistos depended on the wireless network to track movements of large animals, identify weather, gather seismic data, and provide a host of other information. The data network served as warning, science, and reassurance all at once.

I would be Joseph’s help, bringing him water, asking him questions from the others and relaying answers, recording as much as I could in my pad for us to talk about later. I would make sure he ate.

We crossed Park Street, heading for the science guild hall. Garmin and Klia and May walked toward us. They were all roughly our age, and in a hurry; at risk of being late for work across the river in the industrial complex. Klia looked up and saw us, and elbowed Garmin, who glanced our way and grasped Klia’s and May’s hands, pulling them toward the other side of the street, away from us.

“Good morning, Garmin!” I called, my voice as loud and cheery as I could make it be.

Garmin glared at me, just for a moment, and I expected him to say something mean. But he only turned and whispered to Klia, who watched the ground. I heard the words, “. . . darn mutants. They shouldn’t be allowed out.”

I was mutant enough to hear his whispered words, but not rude enough to reply. Joseph scowled, but he, too, ignored them.

May watched the park intently, as if she expected something scary to pop out of the grass and frighten her. Or as if she just didn’t want to look at us. If we’d passed May alone, she might have nodded politely, maybe even have said hello. In groups, almost none of the kids our age were even that polite. Joseph and I glanced at each other and walked faster, getting distance between us and Garmin. We didn’t look back until we ducked into the science guild door.

The main room of the science guild hall was large enough for five hundred people. Offices, labs, and meeting rooms lined two sides of the building. The walls were wood from the Lace Forest, the roof tiles made of molded riverbank clay. The builders guild makes us glass windows, hauling sand up from the beaches and across the Grass Plains after the fall burn, when the grass is low enough for safe travel. Guild members set the thick windows loosely in clever slides designed to survive the frequent small earthquakes that plague Fremont.

When we arrived, Nava, Tom, and Paloma waited for us in the monitoring room. Nava frowned when we came in, her green eyes an icy contrast to her red hair. “You’re late.”

We weren’t late, we were just last. I ignored her, accustomed to her coldness, her resentment of every use the colony made of our skills. Her husband Tom, a dark-haired, stocky, and round-faced gentle bear of a man, greeted us more warmly, smiling and handing us glasses of apple juice. We drank, and I ushered Joseph to the soft blue chair Steven designed so he could lie curled in his favorite monitoring position, hands and feet drawn up into a ball. It was more like a little round bed than a chair, although Joseph could sit up in it when he liked. He almost never did.

Paloma stood in the far corner of the oblong room, her back to us, poring over logs from the night before. “Traveler,” she said to no one in particular, “reported two small chondrite asteroids last night. One burned up on entry and the other landed in the ocean.”

Tom grunted. “Could have been big ones. Gianna said we’ll be in the storm for months. It’s the worst on record.”

“Let’s just hope all the big ones miss us,” Paloma muttered, her words almost a prayer. Only when she completed the logs did she look over and smile at us. She was Kayleen’s adoptive mother, and she treated us, and our gifts, our alterations, as normal. I loved her for it. Even Steven and Therese, who stood up for us, did not treat us as if we were like them. Paloma grinned. “They’re leaving. Are you ready?”

Joseph drained his apple juice, handed the glass to me, and leaned in to take my hand. “Blood, bone, and brain,” he murmured, reciting the words he and Kayleen used to trigger the changes in their consciousness that hooked them into the data nets. “Take care of me, sis.” He smiled, falling away from me, his eyes closed, his face relaxing, slack, as if he were sleeping, as if he were dreaming a good dream. He loved nothing more, then, than to feel and hear his body sing with data.

Today’s repair team included our adoptive parents, Steven and Therese, who led the colony. They rarely left Artistos’s boundaries, tethered by their responsibilities. Perhaps it was the easy summer, the comparative rest, that drew them out.

All together, there were ten, a large group, mostly because they planned to hunt for djuri. Djuri flesh is soft and almost sweet, tender, a treat when you are accustomed only to goats and chickens. Djuri herds often come near us in winter, but they stay higher in summer, and today the team took the High Road. We all hoped for a feast.

The team was tied to us by four of the increasingly rare earsets that allowed people any distance apart to talk, using the satellite network and ground-based wireless nodes to beam clear voice anywhere inside the wireless net. I’d been allowed to use one twice on trips to the Grass Plains with Therese and Paloma to catalog species, and they tickled my ear inside. We could not make new ones here yet; every one we lost reduced our communications ability. Joseph though, Joseph could hear the earsets without...

Copyright © 2007 by Brenda Cooper

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details