Added By: Rhondak101

Last Updated: valashain

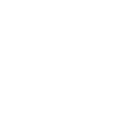

Night Pilgrims

| Author: | Chelsea Quinn Yarbro |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2013 |

| Series: | Count of Saint-Germain: Book 26 |

|

0. Cabin 33 |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy / Horror |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro's first Saint-Germain novel, Hotel Transylvania, was recently nominated as Vampire Novel of the Century. Her Saint-Germain cycle, now comprised of more than twenty-five books, is a masterwork of historical horror fiction. The vampire Count Saint-Germain has crisscrossed the world many times, seeking love and the blood of life and seeing humanity at its best and worst.

In Night Pilgrims, Saint-Germain is living in a monastery in Egypt when he is hired to guide a group of pilgrims to underground churches in southern Egypt. The vampire finds a companion in a lovely widow who later fears that her dalliance with the Count will prevent her from reaching Heaven.

The pilgrims begin to fall prey to the trials of travel in the Holy Lands; some see visions and hear the word of God; others are seduced by desires for riches and power. A visit to the Chapel of the Holy Grail brings many quarrels to a head; Saint-Germain must use all his diplomacy and a good deal of his strength to keep the pilgrims from slaughtering one another.

Excerpt

Part I

Rakoczy, Sidi Sandjer'min

Text of a letter from Sieur Horembaud du Langnor at Alexandria to Rakoczy, Sidi Sandjer'min, written in Latin, and carried upriver to the Monastery Church of the Visitation; delivered twenty-three days after it was written.

To the renowned European teacher known here as Rakoczy, Sidi Sandjer'min, greetings from Sieur Horembaud du Langnor, once Crusader, now penitent, bound for the churches and shrines in the far south, on the Feast of the Circumcision, in the Year of Grace, 1225.

I am told by several well-informed Christians here in Alexandria that you are the man I must address in this predicament. I am seeking a translator and guide to assist in my pilgrimage to the south, into the mountains beyond the ancient Empire of Axum, which will set out from your monastery within a month of my arrival in that place. You, I am informed, know well the ways of the Nile and have many languages at your command, which will be most useful: I am intending to find a number of like-minded Christians to accompany me and my servants on my journey to the Christians of the Horn. As few Europeans are willing to guide us, lacking sufficient knowledge to undertake this pilgrimage, I believe it is God's intention that you will accept the commission, for it is said you understand the risks of journeying beyond the limits of Egypt; you are vastly traveled, or so I have heard, and that would mean that you are especially well-prepared to supervise our journey. Also, you know the customs of the Christians of the region, and will be able to assist us in showing proper regard for their ceremonies, and to be able to lead us to the holiest shrines and churches.

I would expect that we will be gone on this pilgrimage for a year or so. Those who have made the journey themselves have told me that it will take that long to travel into the mountains beyond the desert, to visit the holy sites, make proper obeisance at each of them, and to return. I have been told that at the height of summer, rains begin in the mountains, and that until autumn, the rainfall continues, and slows travel in those distant places. All those going must be prepared for hardships, but such devotion is pleasing in God's sight, or so the priests have said.

It is important to me to do this, for unless I perform this penance, I may not lead my troops again, by order of the Bishop of Acre. This was due to an error from local guides who assured me that there were Islamites in the town we had reached, and said they were preparing to poison the wells. As soldiers loyal to the Church and Christ, we went in and killed the people, and only then discovered that the people of the town were Christians of the Eastern Rite, and that we bore their deaths on out souls. I am eager to rejoin my troops so that we may stem the tide of Islamites that plagues the Holy Land, as any true Christian in this place would be, and therefore I have decided to address a European to guide me and my pilgrims, so that we should not be tempted to sin again, and who could offer testimony that the terms of my penance has been fulfilled. All those who have been on Crusade know to their costs how easily one can transgress. To that end, I am hoping to secure relics for Saunt-Adrien-le-Berger in the Aquitaine, where my fief is located; relics will surely help me in being restored to command of my troops and bring distinction to my family. I long for battle in the cause of Our Lord, Who made me to be a warrior in His Name. To wear armor again, to wield my sword in the name of the Savior: what Christian knight can ask for more?

Not that pilgrims can go armed into those lands beyond Egypt, for that has been forbidden since the First Crusade, when only unarmed Christians were allowed to enter Jerusalem, which stricture is still in force there. Hunting weapons are allowed, but the weapons of war and the armor that goes with them are not, and failure to comply with this order of disarmament brings a most unpleasant death. Enforcement of these restrictions is severe, by all reports. We will need to find men to accompany us who are skilled hunters, not Europeans, which would make us more vulnerable to attack and capture, but from Egypt and Christian. I am not minded to trust any Islamic hunter in our numbers, for they will put their faith ahead of ours. Since you are already among Christians, the search should not be a difficult one. I will leave such things up to you. God has pointed the way to you, and I will bow to His Will, as will you, for the sake of our faith, if you are the man I have heard you are. You are the man I seek; if you will pray, you will learn what God has revealed to me, and you will place yourself in my service, for it is the service of God.

I authorize you to bring with you up to six men, and will bear the cost for their travels; food, water, and shelter will be their concern, and yours, to the limits of my purse. When I and my pilgrims arrive where you are, you will advise us on what we need for our journey and where to obtain it; I have two servants with me, one of whom is a fine judge of camels and should be able to find worthy beasts for us once we need them. This is an endeavor worthy of any Christian, and one that many saints have undertaken. It is unfortunate that we must travel in summer, and therefore at night, but God has willed it so, and we must take His Gifts as He offers them. Be ready to receive us and we will welcome you to our numbers.

Sieur Horembaud du Langnor

by the hand of Frater Anteus, Ambrosian

2

Sandjer'min studied the letter that a monk called Yaboth had brought to him in the scriptorium behind the chapel. "Sieur Horembaud du Langnor, in the Aquitaine," he mused as he read the message a third time. "He certainly knows what he wants."

"Is it important?" Yaboth asked, hesitating a bit as he spoke while he peered at the letter he could not read. He was middle-aged, about thirty-five, with a long, tangled beard and fingers gnarled from his years of copying.

"It may be," said Sandjer'min. He set his stylus aside and looked down at the page of formulae for medicaments, part of a book of remedies he was preparing for the monastery. "But that depends on Malik-al-Kamil more than on Sieur Horembaud."

Yaboth looked askance. "What has the Sultan of Egypt have to do with a Christian knight?"

"Directly, I would think very little, but if the Sultan has decided to banish most Europeans from Egypt, then it may have everything to do with him, and me."

"There has been no word of such a ban yet, Sidi," Yaboth said, not looking directly at Sandjer'min.

"But if it comes, then I must consider Sieur Horembaud's request seriously." He gazed out through the unshuttered window into the warm afternoon. "I shall be sorry to have to leave here."

"Do you want to send this Sieur Horembaud an answer?"

"It seems unnecessary. He is planning to stop here on his way south in any case." Getting off the writing stool, he began to refold the letter, sliding it into the sleeve of his cotehardie when he had done, then closed his dish of ink and covered his ink-cake, a mixture of powdered charcoal, rat-skin glue, and ground marsh-berries. "It's time I go to Aba'yam."

"He is improving, isn't he?" asked Yaboth, more doubt in his voice than he liked.

"Yes, he is improving, but he still needs to become better; why do you ask?" Sandjer'min regarded Yaboth with a penetrating gaze. "Is Tsura'gar persisting in seeking to replace him as Aba'yam?"

"He says not, but who knows the hearts of men but God." Yaboth said unhappily. "He has said that the continuing pain in Aba'yam's foot is a sign that he is no longer fit to lead the monastery and that we should elect a successor."

"An unfortunate situation," said Sandjer'min.

Yaboth scowled. "Has he said anything to you--Aba'yam, not Tsura'gar? Do you know what he is planning to do?"

"What would he say to me? I am a foreigner not of your faith. It would not be advisable for him to speak to me about the monastery or the monks. For the most part, we discuss his progress and the treatment I provide." This was not entirely true, but he did not want to break Aba'yam's confidence. He gestured his farewell for the day and left the scriptorium, walking around the front of the chapel, past the refectory to the dormitory, where he knocked to summon the monk who supervised the building. "I am here to--"

"I know what you are here for, Sidi," said Tsura'gar, his head slightly lowered, not in humility, but like a bull preparing to charge. He was the biggest man in the monastery, almost a hand taller than Sandjer'min, bigger framed than most of the Copts, with dark-brown hair hanging in disordered curls to his shoulders, and honey-colored eyes. "Aba'yam is waiting for you in the wash-room."

"Very good," said Sandjer'min.

"Shall I escort you?" His stare challenged Sandjer'min to refuse.

"As you like. I do know the way," said Sandjer'min with no indication of annoyance. "But do as you think best."

"Then it is best that I show you," said Tsura'gar. He set out to trudge along the narrow corridor and up the half-flight of stairs at the end of it.

"Did Aba'yam soak his foot this morning?" Sandjer'min asked as they went up the steep steps.

"He did, and prayed while he did it." There was a edge of defiance in his answer, as if he regarded Sandjer'min's medicaments as a kind of rival to God's capacity to work miraculous cures.

"Very good," Sandjer'min said, refusing to be drawn into an unnecessary dispute.

Near the top tread, Tsura'gar stopped and rounded on Sandjer'min, on the step below; taking full advantage in the difference in height this gave him, he loomed over the foreign Sidi. "You will not suborn him with your foreign wizard's tricks. He will not forfeit his soul to be spared suffering of the body."

"I have no wish to do other than return him to good health," Sandjer'min said calmly, his enigmatic gaze meeting Tsura'gar's stare.

"That is God's work."

Sandjer'min studied Tsura'gar's face, wondering to whom the monk had been talking, that he so reviled Sandjer'min's efforts to help Aba'yam; whoever it was, his influence must be growing stronger for him to condemn Sandjer'min's efforts so rigorously. "Which is why God gives us medicinal plants and treatments, that His Will may be done. It would be irreligious not to use what he has given for our good." He saw Tsura'gar's frown deepen to a glower. "Why do you doubt this?"

"Because you are not a Christian!" Tsura'gar burst out, his face thunderous. "You have not been baptized! You have not Confessed!"

Sandjer'min favored Tsura'gar with a sardonic smile. "At least I am no hypocrite. You monks have known that I am not of your faith since I came here, and raised no cry against me, until now," Sandjer'min reminded him with unflustered calm. "None of you protested my being here before the Sultan's messengers arrived."

"Because Aba'yam welcomed you, and Venerable Minseh made no objection."

"What do you hold against me, then, if Aba'yam and your Venerable have accepted me?"

"Because I know the Devil sent you." There was absolute certainty in Tsura'gar's deep-set eyes. "You are his servant."

"If I were, what good would it do for me to treat monks and your fellow-Christians for injuries and illnesses. How would that serve the Devil?" He waited to hear Tsura'gar's answer.

"You seek to turn us away from God," Tsura'gar insisted. "To mistrust His Mercy."

"How could treating the sick do that?"

"There are things in your medicaments that will cause us to turn us away from faith. You are a corrupter of holy men, with your foreign ways and your--" Tsura'gar folded his arms so he could more completely block the last two steps to Sandjer'min. "You have come here to lead us to tergiversation."

"By treating your ills?" Sandjer'min persisted.

Tsura'gar had no answer for this, and barreled on, "You have insinuated yourself into Aba'yam's good graces and you are using that to destroy him. You think I haven't been watching you, but I have, and I see what you are doing."

"I am treating Aba'yam for a deep putrescence in his heel which--"

"You put it there, with your potions and ointments and soaking! You are slowly poisoning him." He raised his fists, trembling with the effort to keep from using them.

"Aba'yam had a the end of a thorn sunk deep in his heel; sand worked itself deep into the wound and irritated the tip of the thorn. That is what caused the putrescence and made it impossible for the wound to close. Now it is almost--"

"There was a thorn, probably poisoned, because you--" He stopped abruptly as Sandjer'min came up next to him, took him by the shoulder and held him against the wall without apparent effort.

"Listen to me, Tsura-gar: I have done all that I know to do to return health and strength to Aba'yam, as I have done for other monks, and those of the faithful who have come here for succor. I do it out of my obligation to you for giving me a safe haven here. No one has complained of either my work or my reasons for doing it, not even those among you who are suspicious of me, or not until now." He spoke softly, almost gently, but with such purpose that Tsura'gar goggled at him and squirmed in his relentless grip. "I have no reason to do any of you harm." He took a half-step back--all the narrow stair would accommodate--and released Tsura'gar. "But rest assured, I will shortly be gone from here. You haven't long to wait."

"How long?" Tsura'gar asked, the question itself an accusation of lying.

"A month at most." As he said it, Sandjer'min knew he was committed to leaving. "I have been asked to join a group of pilgrims going south."

Tsura'gar showed his teeth in what was not quite a smile. "I will inform Venerable Minseh of this. He will be much relieved," he said nastily.

"I would have thought it was Aba'yam's responsibility to do that," said Sandjer'min with maddening calm. "If you will excuse me, I have to attend to Aba'yam now. If you feel you must, you may lambaste me again when I am finished." Without waiting for any response, he climbed the last step and entered the wash-room, to find Aba'yam waiting for him, his foot plunged into a large bucket of steaming water; the room smelled of salts and wet hemp. Next to it Sandjer'min's medicament case was sitting, its straps unbuckled.

"I heard you talking with Tsura'gar," Aba-yam said, keeping his voice low. "He will have to do penance for his accusations."

Sandjer'min pulled up a low stool and sat down next to the bucket. "If you would help me, say nothing to him: he is looking for reasons to think ill of me, and such penance would give him another injury to increase his rancor. Any attempt to hold him to account will strengthen those who oppose you." He lifted Aba'yam's foot from the hot water, examining it carefully, testing the skin around the ruddy new scar on his heel. "Are you having much pain from walking?"

"A little, but as you told me would happen, it is decreasing. I have walked twice as far yesterday as I had been able to the week before. In a month, I hope to be fully restored. In the meantime, I will continue to wrap my foot before I don my sandals when I must walk across sand--even a little sand. I think you were right in fearing that sand in the wound was making it worse." He flexed his foot. "You see? Now that the swelling has gone down, I can move much more easily."

"Good, but not quite as supple as it could be," Sandjer'min told him.

"How long do you think it will be before it is fully strong again?" Aba'yam asked this without any show of worry, though his eyes were a bit too bright.

"A year, perhaps a bit more," Sandjer'min said. "The putrescence has been deep, so it will require time to leave your body completely."

"A year? So long," Aba'yam marveled unhappily.

"Such obdurate putrescence can take longer than that to heal. If it had spread, you would have lost your foot and perhaps your life."

"So you warned me," Aba'yam said, letting his foot sink into the bucket again. "But a year seems a long time for a man of my age; I have fewer years ahead than behind me."

"I suppose it must," said Sandjer'min distantly, trying to recall how it had seemed to him before his unsuccessful execution, when he was thirty-three breathing years old, thirty-three centuries ago.

"It may not appear to be so long a time to you. You are a grown man but not sunken in years, as I am," said Aba'yam.

Sandjer'min smiled faintly. "I am older than you may believe."

Aba'yam shook his head. "I will accept your conviction, but I can't imagine you are much more than thirty-eight or -nine."

Not wanting to continue on such potentially dangerous observations, Sandjer'min asked, "How long have you been soaking your foot?"

"Not as long as you would prefer, I suspect." He lifted the foot. "The skin isn't shriveled yet."

"True enough. Keep it in the water a little longer." He unbuckled the strap that held his case closed. "Have you been eating lemons with your midday meal?"

"Not every day, but most of them." Aba'yam yawned, then blessed himself so that his soul would not escape his body. "I could have more if you require it, though I don't like the taste."

"If you dislike the taste, then don't eat more than you're doing already."

Aba'yam shook his head a second time. "Thank you. My mouth puckers at the thought of lemons. Why do you want me to eat them?"

"They bring the sun into your body," he said, giving the explanation he had heard in Persia when he and Ruthier had traveled into China almost two decades ago.

"Haven't we sun enough in Egypt?" Aba'yam joked feebly.

"Not for the inside of your body," Sandjer'min said seriously. "I hope you will continue with the lemons, for your sake."

"Very well," said Aba'yam.

"If your teeth start to hurt, you may stop for a while, say for a week at most," Sandjer'min told Aba'yam, then gave his attention to laying out his medicaments. When he was satisfied with his work, he asked "How much longer will you be able to continue not leading the monks in the rites of your monastery?"

"Before Tsura'gar confronts me for Aba'yam?" he asked. "The Procession of the Annunciation to Holy Marya is in a few weeks; I will have to participate fully. As you may be aware, the monastery takes its name from what followed that holy occasion, and therefore I must lead or become Bulo'the again, and go into one of the old desert caves to fast and pray for salvation from my failure."

Knowing it was useless to argue about this, Sandjer'min said to him, "If leading a procession is your greatest trespass, you may count yourself a most fortunate man."

"All sins, even the smallest, are abhorrent in God's eyes," Aba'yam said sternly, looking directly into Sandjer'min's dark eyes. "Repentance is needed, or salvation is meaningless."

"Surely God understands the nature of your errors and assesses them with that in mind," said Sandjer'min, remembering how different the teachings of the earliest Christians had been from those that now predominated the liturgy and the tenets.

"God's sacrifice of His Son demands our repentance," Aba'yam insisted.

Sandjer'min wondered what Aba'yam had done that made him believe years of isolation and penance was required of him; he kept the question to himself, and instead broached the matter that had claimed his attention for most of the day. "I have received a letter from a Christian knight who is escorting a group of pilgrims into the lands to the south. He has... asked that I go with his company, and I am inclined to acquiesce; he wants someone who can speak to the peoples of the south."

"Do you know those tongues?" Aba'yam asked, startled.

"No," Sandjer'min admitted. "But one of your monks must, and may be willing to go with us. I should know the languages of the pilgrims." He took a deep breath and continued, "It is time my manservant and I were gone from here; it would be poor repayment for your hospitality to bring the Sultan's men down upon this place because of my presence." It was true as far as it went, but there were other factors that had become pressing--there were few women in the village that he could visit in dreams and none whom he could as knowing lovers--and spurred him to decide on leaving. With Tsura'gar and his faction against himself and Aba'yam, the protection the monastery afforded the three of them--for surely Ruthier was equally at risk as Sandjer'min and Aba'yam--would not last long.

"Is there any way I might dissuade you?" Aba'yam asked, the vertical lines between his brows deepening.

"I doubt it; it wouldn't be wise of you," he said. "Let me treat and bandage your foot, Aba'yam, and then I will arrange with Ruthier to make ready for our departure, so that when the knight arrives with his pilgrims there need be no delay."

Aba'yam's sigh was a complicated one: resigned, exasperated, regretful, fatalistic, and slightly bored with the process of treating his foot. "For now, I will say nothing, in case you should change your mind," he said as Sandjer'min anointed his foot.

"I do not think that will happen," said Sandjer'min.

"Then I will pray for you," said his patient.

It was two days later when Zekri, a monk from up-river near the Second Cataract, whom Sandjer'min knew from his work in the scriptorium, came to Sandjer'min's little house and asked if he could have a word with him.

"If you'll step in out of the sun," Ruthier said, "I will ask him if he's--"

Sandjer'min appeared in the doorway to the second room. "It's all right, Ruthier. I'll talk to the monk."

Ruthier nodded. "My master." His glance in the monk's direction told him the young man needed to speak privately with Sandjer'min, and so he turned to him and asked, "Would you object to my leaving you alone while I go fetch a rabbit? I shouldn't be gone long. I'll be back as soon as possible."

"By all means, fetch the rabbit." He indicated the door; Ruthier left promptly. "Now, Zekri, why are you here?" he asked, taking his place on the tall stool at the work-table.

"I was hoping you might need a guide for your travels to the south," he said with unusual directness; he blushed and stammered, "I have h-heard that you're g-going upstream. I--I know t-the way. It's not-t easy to f-follow the Nile. I c-could help. My v-village is south of h-here. I've b-been beyond the F-fifth Cataract with my f-father, and I know s-some of the t-tongues along t-the way. I know some f-few words of Umo and Barwa." He tugged at the sleeve of his habit, his black eyes moving uneasily; he was lean and angular, a young man still showing the awkwardness of youth. "I c-can vouch for wat-termen along the river."

"Indeed," said Sandjer'min, his face and eyes revealing nothing of the flare of curiosity that had ignited within him. "And how do you know about this? About my coming journey?" He knew Aba'yam had said nothing about his plans, which meant they had been overheard when he was treating Aba'yam's foot..

"Monks t-talk," said Zekri.

"So they do," said Sandjer'min, and motioned him to continue.

"Yes," said Zekri, continuing with more confidence. "I have been that far t-twice, to the Fifth Cataract. My f-father had been across the Nubian Desert into the mountains four times; he would have g-gone a fifth time, but he took ill and d-died before he could leave again."

"It is true that it would be useful to have a guide. I have been to the Third Cataract, but it was some time ago." It had been more than a millennium since he had made that journey; he kept that to himself.

"The river changes over time. My knowledge is no more than five years old, and should be adequate to the pilgrims you will guide. It is pilgrims, isn't it?" He looked at Sandjer'min directly, and then his eyes flicked away. "I know men in the stops along the river, which I doubt you do."

"You would be correct," said Sandjer'min. He waited, curious to see how long Zekri could go without speaking.

After a short silence, Zekri said, "I have other knowledge, some from my own travels, some from my father's accounts. For my own, I know what animals dwell along the Nile, and in the Nile, and I have been taught how to deal with the dangerous ones. I have been told of the dog-faced moneys and the wolves in the mountains." He saw Sandjer'min's dark eyes widen. "Oh, yes, there are wolves. They are high up, and they hunt in packs. There is more I've learned that can help you: I know what to look for to be safe from c-crocodiles and hippopotami, and where snakes go to nest. I have heard of all the animals in the mountains and the d-deserts, but have not seen them all."

"I know some of these things, as well. I have seen dog-faced monkeys, but not, I admit, the wolves you speak of. I know jackals and snakes and many kinds of birds." He considered the monk carefully, aware that a second pair of well-informed eyes could be useful as they traveled; he shrugged. "Still, if Aba'yam and Sieur Horembaud are amenable, you may come with me as one of the men I am allowed to bring."

Zekri smiled uncertainly. "Shall you tell Aba'yam that?"

"If you like," said Sandjer'min. "I will see him again tomorrow and will bring this up to him. I'll let you know what he decides."

Zekri ducked his head. "Thank you, Sidi."

"May I ask why you want to go with us?" The question was little more than an impulsive afterthought, but he saw alarm in Zekri's face. "Is there some trouble?"

"No; I seek to avoid trouble, Sidi," the young monk answered, flushed deeply, and went silent.

Sandjer'min wondered what the trouble might be, but decided not to ask; if Zakri wanted to tell him, he would wait for him to speak. "Very well. But I will give you two days to change your mind, if you should decide to stay."

"I won't," said Zekri with such force that Sandjer'min realized that the monk was not simply asking to journey upriver with him, but was seeking to escape something or someone within the monastery itself.

"Nonetheless," Sandjer'min said calmly, "I would be easier in my mind if you gave yourself a little time to consider what you're undertaking."

"If you insist, I'll p-pray, but I won't change my mind; if I do not go with you, I will still leave this place," said Zekri, his hands clenching, punctuating his determination. He studied the few remaining dried herbs on the hooks behind the work-table. "You will bring your medicaments, won't you?"

"I will," he said.

"G-good." Zekri stood awkwardly, trying to summon up something more to say, then muttered a few disjointed words of thanks before he turned abruptly and left.

A bit later in the afternoon, Ruthier returned, a skinned rabbit hanging from a cord around his wrist. He stepped through the door, pausing as he crossed the threshold. "What did Zekri want?" He spoke in Imperial Latin.

"He wants to join the pilgrimage," said Sandjer'min in the same language, pausing in his loading a wooden chest with his clothes.

Ruthier cocked his head. "Interesting. Did he say why?"

"He knows the river for a considerable distance to the south, and thinks he can be useful," Sandjer'min said with supreme neutrality.

"Then there is more than that," said Ruthier, taking the cord from around his wrist and slipping it over a peg, the rabbit hanging against the wall.

"It would seem so," said Sandjer'min, then changed the subject. "How are things in the village?"

Ruthier knew Sandjer'min would not discuss Zekri again for a while, so he said, "There's much concern about the Sultan's messengers. The villagers are afraid they'll lose all their young men to the Sultan's army. A few are planning to enter this monastery to keep from having to serve the Sultan." He hesitated. "Would you want to take any of them with us? It would remove them from the Sultan's grasp without having them resort to entering the religious life."

"To go south with the pilgrims? That would be for Sieur Horembaud to decide, not I." Sandjer'min was aware that Ruthier's dismay came from something more than the plight of the local villagers, but said nothing.

"What if you were to recommend a few of them? They're Christians, and there would be merit in helping them, would there not?"

Sandjer'min shook his head. "No, not as things stand. It could cause problems for the villagers and the monastery if we did."

"What do you think it would lead to?" Ruthier asked, not as convinced as Sandjer'min was that there could be trouble. "The village is small. The Copts are important to the village, but not much beyond its limits. Sese'metkra would seem hardly worth the effort to conscript its young men. At most there would be twenty young men who could be taken for soldiers, leaving the village without the means to plant and harvest as they have done."

"I agree. This is the sort of place where an example can be made, where opposition can be cut short with little effort on the Sultan's part," Sandjer'min said. "There aren't enough villagers to stand against the Sultan's men, so it is comply or be crushed, which would serve as a warning to other Coptic villages to do as the Sultan commands. It would also mean that many of the people would be pressured to convert, so they would be allowed to keep one son at home."

Ruthier took a deep breath. "And that would imperil the monastery and the village, having such conversions."

"Very likely," said Sandjer'min.

"To lose children or to lose one's faith," Ruthier mused. "Not an easy choice for these people."

Sandjer'min nodded. "And our presence makes it more complicated, for of the town turns away from the monastery, we will have to leave quickly."

"I agree. But do you think that would spare the young men of the village?"

"I don't know, but I would guess not." The world-weary tone of Sandjer'min's answer reminded Ruthier of their days on Cyprus and in Spain.

"You're probably right." Ruthier took a short while to think. "I was thinking of my children, my master. Had this happened in Gades when I was still alive, I would have wanted the chance to keep them out of the hands of those who fought against us, and that wouldn't be possible if I joined with those enemies." It had been almost twelve centuries since Ruthier had been restored to life by Sandjer'min, and longer since he had been separated from his family, but the poignancy of the loss had never left him.

"You understand the impasse here," Sandjer'min said.

"And I sympathize with every villager family with boys between fifteen and twenty."

Sandjer'min nodded slowly. "I have no doubt of that, old friend."

"Why would the Sultan not spare a few of the--"

"--villagers' sons? It would be a false delivery, I fear." Sandjer'min stared thoughtfully into the middle distance. "Who would decide which boys were to be exempt and which were to be taken? There would be dissension and the village would face reprisals if there were any kind of refusal."

"Arbitrary selection of young men would not gain the villagers' approval," said Ruthier.

"I don't believe Malik-al-Kamil is worried about the approval of a few Copts," said Sandjer'min. "He needs to strengthen his army."

"A pity he won't spare a few Copts from the war," said Ruthier, more sharply than was his habit.

"But where would it stop? He would end up having to excuse all Copts from his conscription, and that would compromise his forces. I am not defending him," he added, seeing Ruthier's glower. "I am only describing the Sultan's predicament. If he does not take all the young men he can, he will lose before the first battle occurs. That does not mean that I am in favor of what he believes he must do, but my opinion means little here."

"Then you think Jenghiz Khan will get this far?" Ruthier asked.

"No, but I didn't think he'd get so far into China, or the west," said Sandjer'min.

Ruthier took a long moment to think this over. "You're right: it is time we were gone," he said at last, and went to take his dinner into the second room.

Copyright © 2013 by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details