Added By: valashain

Last Updated: Administrator

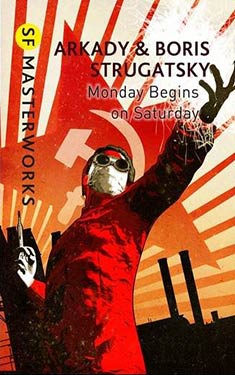

Monday Begins on Saturday

| Author: | Arkady Strugatsky Boris Strugatsky |

| Publisher: |

Gollancz, 2014 DAW Books, 1977 Original Russian publication, 1965 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Light/Humorous SF Time Travel Weird (SF) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Film & Television Adaptations

Synopsis

When young programmer Alexander Ivanovich Privalov picks up two hitchhikers while driving in Karelia, he is drawn into the mysterious world of the National Institute for the Technology of Witchcraft and Thaumaturgy, where research into magic is serious business.

And where science, sorcery and socialism meet, can chaos be far behind?

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

Teacher: Children, write down the sentence "The fish sat on the tree."

Pupil: But do fish really sit on trees?

Teacher: Well... this fish was crazy.

-- A school joke

I was nearing my destination. On both sides the green forest pressed right up against the road, giving way now and then to clearings overgrown with yellow sedge. The sun had been trying in vain to set for hours and still hung low over the horizon. As the car trundled along the crunching gravel surface of the narrow road, I steered the wheels over the large stones, and every time the empty gas cans in the trunk clanged and clattered.

Two figures emerged from the forest on the right, stepped out onto the edge of the road, and halted, looking in my direction. One of them raised his hand. I eased off the accelerator as I examined them. They looked to me like hunters, young men, perhaps a little older than me. I liked the look of their faces, and I stopped. The one who had raised his hand stuck his swarthy, hook- nosed face into the car and asked with a smile, "Could you give us a lift to Solovets?"

The other one, who had a ginger beard but no mustache, peeped over his shoulder, also smiling. They were definitely nice people.

"Get in," I said. "One in the front and the other in the back -- the backseat's pretty cluttered."

"Our guardian angel!" the hook-nosed one exclaimed delightedly, slipping his gun off his shoulder and getting into the seat beside me.

The one with the beard glanced in uncertainly through the rear door and said, "Do you mind if I just...?"

I leaned over the back of my seat and helped him clear the space that was occupied by the sleeping bag and folded tent. He sat down cautiously, setting his hunting gun between his knees. "Make sure you close the door properly," I said.

So far everything seemed normal. I drove on. The young man with the hooked nose turned to face the back and started talking boisterously about how much nicer it was to ride in a car than to walk. The young man with the beard mumbled his agreement and kept trying to slam the door shut.

"Pull in your raincoat," I advised him, looking through the rearview mirror. "Your coat's jamming it."

Five minutes later everything was all sorted out. "About ten kilometers to Solovets, isn't it?" I asked.

"Yes," replied the hook-nosed one. "Or maybe a bit more. Only the road's not so good, of course -- it's just for trucks."

"The road's just fine," I retorted. "I was told I wouldn't be able to get through at all."

"You can get down this road even in autumn."

"Here, maybe, but from Korobets on it's a dirt track."

"It's a dry summer this year -- everything's dried out a bit."

"They say there's rain up around Zaton," remarked the bearded young man in the backseat.

"Who says?" asked the hook-nosed one.

"Merlin says." And for some reason they laughed.

I took out my cigarettes, lit up, and passed them around.

"The Clara Zetkin Plant," said the hook-nosed one, eyeing the pack. "Are you from Leningrad?"

"Yes."

"Doing a bit of traveling?"

"Yes," I said. "Are you local?"

"Born and bred," said the hook-nosed one.

"I'm from Murmansk," declared the bearded one.

"I suppose from Leningrad there's no difference between Solovets and Murmansk -- it's all the North," said the hook-nosed one.

"No, not at all," I said politely.

"Will you be staying in Solovets?" asked the hook-nosed one.

"Certainly," I said, "Solovets is where I'm headed."

"Have you got family or friends there?"

"No," I said, "I'm just going to wait for some guys. They're hiking along the coast, and we arranged to meet up in Solovets."

I spotted a large patch of rocks ahead, braked, and said, "Hold on tight." The car started shuddering and shaking. The young man in the front hit his hooked nose against the barrel of his gun. The motor roared and stones smashed against the bottom of the car.

"Your poor car," said the hook-nosed one.

"Can't be helped," I replied.

"Not everyone would drive down a road like this in their own car."

"I would," I said.

The patch of large rocks came to an end. "So, it's not your car then," the hook-nosed one deduced.

"Where would I get a car from? It's rented."

"I see," said the hook-nosed young man, and I thought he sounded disappointed.

I was stung, so I answered, "What's the point of buying a car for driving around on asphalt? The places covered in asphalt aren't interesting, and in the interesting places there isn't any asphalt."

"Yes, of course," Hook-Nose agreed politely.

"I think it's stupid to turn a car into a fetish," I declared.

"It is," said the bearded one, "but not everybody thinks that way."

We talked a bit about cars and came to the conclusion that if you were going to buy anything, then it should be a GAZ-69 all-terrain model, but unfortunately they weren't for sale.

The hook-nosed one asked, "Where do you work?"

I answered the question.

"Tremendous!" he exclaimed. "A programmer. A programmer's just what we need. Listen, why don't you leave your institute and come to work for us?"

"And what have you got?"

"What have we got?" asked the one with the hooked nose, turning around to the back.

"An Aldan-3," said the one with the beard.

"A very versatile machine," I said. "And does it run OK?"

"Well, how can I put it...?"

"I get it," I said.

"Actually, they haven't debugged it yet," said the bearded one. "If you stayed with us you could debug it."

"We could arrange the transfer in no time at all," added the hook-nosed one.

"What's your line of work?" I asked.

"Like all science," said the hook-nosed one, "our work deals with human happiness."

"I see," I said. "Something to do with space?"

"Yes, space too," said Hook-Nose.

"I'm happy enough where I am," I said.

"A capital city and good pay," the bearded passenger muttered in a low voice, but I heard him.

"That's not the point," I said. "You can't measure everything in money."

"I was only joking," said the bearded one.

"It's just his sense of humor," said the hook-nosed one. "You won't find any place more interesting than here with us, though."

"What makes you think so?"

"I'm certain of it."

"But I'm not."

The hook-nosed one laughed. "We'll come back to that later," he said. "Are you going to be in Solovets for long?"

"Two days at the most."

"Then we'll talk about it the day after tomorrow."

The bearded passenger declared, "Personally I see the finger of fate in this -- there we are strolling through the forest and we run into a programmer. I think it's your destiny."

"Do you really need a programmer that badly?" I asked.

"We need a programmer desperately."

"I'll have a word with the guys," I promised. "I know a few who aren't too happy."

"We don't need just any old programmer," said the young man with the hooked nose. "Programmers are in short supply; they've gotten spoiled, but we need an unspoiled one."

"Yes, that's a bit more difficult," I said.

The hook-nosed passenger started bending down his fingers as he counted: "We need a programmer who is (a) not spoiled; (b) keen and willing; (c) who'll agree to live in a hostel..."

"And (d)," put in the bearded one, "for 120 rubles a month."

"Perhaps you'd like one with wings?" I asked. "Or maybe with a halo around his head? That's one in a thousand!"

"We only need one," said Hook-Nose.

"And what if there are only nine hundred?"

"We'll make do with nine-tenths."

The forest opened up in front of us. We drove across a bridge and trundled on between fields of potatoes.

"It's nine o'clock," said the hook-nosed one. "Where are you planning to spend the night?"

"I'll sleep in the car. How late do your shops open here?" "Our shops are already closed," said the hook-nosed one.

"You can stay in the hostel," said the bearded one. "I've got a spare bed in my room."

"You can't drive up to the hostel," the hook-nosed one said pensively.

"I suppose not," said the bearded one, and for some reason he laughed.

"You could park the car by the police station," said the hook-nosed one.

"This is just plain stupid," said the bearded one. "I'm talking drivel and you're no better. How will he get into the hostel?"

"Yeah, damn it," said the hook-nosed one. "You're right, take one day off work and you clean forget all these little wrinkles."

"Maybe we could transgress him?"

"Oh, sure," said the hook-nosed one. "He's no sofa. And you're no Cristóbal Junta, and neither am I..."

"Don't worry about it," I said. "I'll sleep in the car. I've done it before." But I suddenly felt a terrible longing to sleep between sheets. I'd already spent four nights in a sleeping bag.

"I know," said the hook-nosed one. "Oho! The Lohuchil!"

"Right!" exclaimed the bearded one. "We'll take him to the curving seashore!"

"Honestly, I can sleep in the car," I said.

"You're going to sleep in a house," said the hook-nosed one, "in more or less clean sheets. We have to thank you somehow."

"We can't just slip you fifty kopecks," said the bearded one.

We drove into the town, with its lines of sturdy old fences and massive timber houses built out of gigantic blackened logs, with carved lintels around the narrow windows and wooden cockerels on their roofs. We passed a few dirty brick buildings with metal doors, and at the sight of them my memory threw up the half-forgotten word "emporium." The street was straight and wide and it was called Peace Prospect. Ahead of us, closer to the center of town, we could see two-story cinder block buildings with small open yards.

"The next side street on the right," said the hook-nosed one.

I signaled, braked, and turned right. The roadway here was overgrown with grass, but there was a brand-new Zaporozhets car nestling against one gate. The numbers of the houses hung above the gateways, the figures barely discernible on the rusty tin-plate signs. The alley bore the elegant name of Curving Seashore Street, but its narrow passage was squeezed in between massive old fences that had probably been erected in the days when Swedish and Norwegian pirates roamed these parts.

"Stop," said the hook-nosed passenger. I braked sharply and he banged his nose against the barrel of his gun again. "All right," he said, rubbing his nose. "You wait for me while I go and arrange everything."

"Really, there's no need," I said one last time.

"No arguments. Volodya, you keep a close eye on him."

The young man with the hooked nose got out of the car, hunched over, and wedged himself through a low wicket gate. I couldn't see the house behind the towering gray fence. The main gates were absolutely immense, like the gates of a railway depot, with rusty iron hinges that must have weighed sixteen kilograms apiece. I was astonished when I read the signs, of which there were three. On the left-hand gate there was a respectable-looking blue sign with silver letters glinting behind thick glass:

NIT WiT The Log Hut on Chicken Legs A historical monument of old Solovets

Hanging on the right-hand gate was a rusty tin plate with the legend 13 CURVINGSEASHORE STREET, N. K. GORYNYCH, and below it was a quaint piece of plywood with a crooked, sprawling inscription in ink:

CAT NOT WORKING

Management

"What CAT's that?" I asked. "The Committee for Advanced Technology?"

The young man with the beard chuckled. "Don't you worry about a thing," he said. "This is a funny old place, but everything will be just fine."

I got out of the car and started wiping the windshield. Suddenly I heard a commotion above my head. I glanced up. Settling down on the gate, trying to make himself comfortable, was a gigantic cat -- I'd never seen one like it -- a black and gray tabby. When he finally settled down, he peered at me with his well-fed, indifferent yellow eyes. "Puss-puss-puss," I said automatically. The cat opened its sharp-toothed jaws with polite indifference, emitted a hoarse, throaty sound, then turned and began looking back into the yard, beyond the fence, from where I heard my hook-nosed passenger's voice say, "Vasily, my friend, I'm sorry to trouble you."

The bolt squeaked. The cat stood up and vanished into the yard without a sound. The gates swayed ponderously, creaking and groaning in a quite terrifying manner, and the left-hand gate slowly swung open to reveal the young man with the hooked nose, red faced from the effort.

"Guardian angel!" he called to me. "Please drive in!"

I got back into the car and drove slowly into the spacious yard. Standing at the back of it was a house built of thick logs, and standing in front of that was a low, handsome oak tree with an immensely thick trunk and a broad, dense crown that hid the roof of the house from view. Running from the gates to the house, skirting the oak tree, was a path of flagstones. To the right of the path was a vegetable garden, and to the left, rising up in the middle of a plot of grass, stood a wooden well with a windlass, its logs all black with age and covered with moss.

I parked the car off to the side, turned off the engine, and climbed out. Bearded Volodya also climbed out, set his gun against the side of the car, and began settling his rucksack on his shoulders. "So now you're home," he said.

The young man with the hooked nose closed the gates with a creak and a groan. I looked around, feeling rather awkward and not knowing what to do.

"And here's the lady of the house!" Volodya exclaimed. "Good health to you, Naina Kievna!"

My hostess must have been over a hundred years old. She walked slowly toward us, leaning on a knotty stick, shuffling along on feet clad in felt boots with rubber galoshes. Her face was dark brown; from the center of a solid mass of wrinkles her nose protruded out and down, as crooked and sharp as a Turkish dagger, and her eyes were pale and dull, as if they were covered by cataracts.

"Welcome, welcome, little grandson," she said in a surprisingly resonant bass. "So he's going to be the new programmer? Welcome, dear guest, welcome indeed!" I bowed, realizing that I should keep quiet. Over the fluffy black shawl knotted under her chin, the old granny's head was covered by a cheerful nylon scarf with brightly colored pictures of the Atomium and an inscription in several languages: BRUSSELS INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION. Her chin and upper lip had a sparse covering of coarse, gray stubble. She was wearing a sleeveless padded vest and a black woollen dress.

"It's like this, Naina Kievna!" said the young man with the hooked nose, brushing the rust off his hands as he walked toward her. "We have to put our new colleague up for two nights. Allow me to introduce... mmm..."

"Don't bother," said the old woman, looking me over closely. "I can see for myself." And she ran through the answers to the standard employment questionnaire: "Alexander Ivanovich Privalov, born 1938, male, Russian, member of the Leninist Komsomol, none, no, never joined, never has, none -- but you, my treasure, shall travel a distant road and do business in a public place, and you should beware, my precious, of a wicked man with red hair, come, cross my palm with gold, my darling one..."

"Hm-hmm!" the hook-nosed young man said loudly, and the old woman stopped short. An awkward silence set in.

"You can call me Sasha," I said, forcing out the phrase I'd prepared in advance.

"And where am I going to put him?" the old granny inquired.

"In the storeroom, of course," said the hook-nosed young man, slightly annoyed.

"And who's going to take responsibility?"

"Naina Kievna!" the hook-nosed young man bellowed in the thunderous tones of a provincial tragedian, grabbing the old woman by the arm and dragging her toward the house. I could hear them arguing: "But we agreed!" "But what if he pinches something?" "Keep your voice down! He's a programmer, don't you understand? A Komsomol member! A scientist!" "And what if he sucks on his teeth?"

I turned in embarrassment toward Volodya. Volodya was giggling.

"I feel kind of awkward about this," I said.

"Don't worry about it -- everything will be just fine."

He was about to say something else, but then the old granny roared out, "And what about the sofa, the sofa!"

I shuddered and said, "You know, I think I'd better go..."

"Quite out of the question!" Volodya said firmly. "We'll sort everything out. It's just that the old woman's looking for a bribe, but Roman and I don't have any cash with us."

"I'll pay," I said. By this time I really wanted to leave; I can't stand these so-called domestic altercations.

Volodya shook his head. "Certainly not. Here he comes now. Everything's OK."

Hook-nosed Roman came up to us, took me by the arm, and said, "Right, that's all settled. Let's go."

"Listen, I feel kind of awkward," I said. "After all, she's not obliged --"

But we were already walking toward the house. "Yes she is, yes she is," Roman intoned.

Rounding the oak tree, we came to the back porch. Roman pushed open the leatherette-upholstered door, and we found ourselves in a hallway that was spacious and clean but poorly lit. The old woman was waiting for us, with her hands clasped over her belly and her lips pursed. At the sight of us she boomed out vindictively, "I demand a receipt this instant! All right and proper: received, such-and-such and such-and-such from so-and-so, who has leased out the aforementioned to the undersigned..."

Copyright © 1965 by Arkady Strugatsky

Copyright © 1965 by Boris Strugatsky

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details