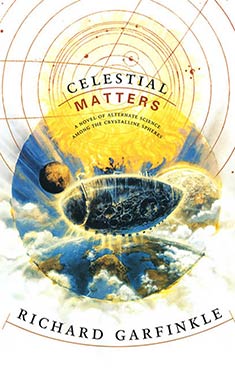

Celestial Matters

| Author: | Richard Garfinkle |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 1996 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

A thousand years after Alexander the Great, the Greek Empire has expanded over the world with the help of advanced technology. Its plans for Total Domination of the entire planet will be complete once the war with the empire of the middle kingdom has been won.

The scientist Aias, commander of the celestial ship Chandra's Tear, prepares to embark on a secret mission to the sun, to steal a piece of the purest elemental fire. This ultimate piece of celestial matter will form the basis for a weapon capable of decisively ending the war with the Taoists of the Far East.

Excerpt

a

I supplicate myself before Apollo of the poets and before the Muses. I ask them to fill me, a weak-voiced scientist, with their gifts so that I may in their honor adorn the tale I must tell with beauty, yet in it say nothing but the truth.

But forgive me, O gods, it is not right that I honor Apollo with my voice and dishonor his father Zeus, god of guests, with my anonymity. Therefore, I tell you that my name is Aias; that I was born in the city of Tyre in the 935the year since the founding of the Delian League; that my antecedents are honorable, since my mother was a child of a great Phoenician merchant house and my father a Spartan general who in his youth commanded armies and in his maturity served as military governor of many city-states within the League.

As for my personal honors, I graduated at the age of twenty from the Athenian Akademe and in the twenty-three years since then I served the League as a scholar in the fields of Pyrology and Ouranology. Most recently I held the post of Scientific commander of the celestial ship Chandra's Tear, and on that vessel I oversaw the researching, creation, and operation of Project Sunthief. It is because of my actions in that capacity that I am now called and do freely submit myself and my story to the gods for judgment.

Once again I bow before Phoibos and the Nine who follow him, and offer prayers for their assistance. With their help and your indulgence, therefore, permit me to begin my table during the last peaceful period in my life, that final stretch of pleasant time the Fates gave me before they snarled the thread of my existence.

For three years I had been in command of Chandra's Tear, during which time I and my subordinates had by the labor of our minds and the experiments of our hands brought Project Sunthief from a theoretical possibility to an incipient reality. At the end of those three years, we were actually capable of spinning celestial matter mined from the inner planets into a sun net. We believed and hoped that we would be able to use such a net to capture a portion of 'Elios's celestial fire.

But the exact specifications of the sun net still required a great deal of patient calculation and experimentation that could only be performed by Mihradarius, my chief Ouranologist. No other progress could be made until he finished that part of the project. When I put the matter to him Mihradarius passed a few minutes in silent contemplation, then confidently declared that he would be able to complete the work in a month.

So, much to our surprise, I and my other two primary subordinates, Kleon, chief Celestial Navigator of Chandra's Tear, and Ramonojon, the Chief Dynamicist, found ourselves with nothing to do for thirty days. We each decided to take advantage of this unexpected gift of time to take leave from the ship.

Of the thousand days that had passed since my crew had first assembled on Chandra's Tear not one of us had spent more than ten on the earth. I do not know how the others felt, but I had come to dream of once again walking across Gaea's stationary ground, and laying my motion-wracked body on her peaceful grassy surface, and enjoying the stillness of that static globe that lay at the center of the endlessly moving cosmos.

I sent messages down to Earth requesting permission from the Athenian bureaucracy, the Spartan military high command, and the Archons on Delos for a month's vacation for the three of us. Both of the Archons approved without comment. The Spartans had no objection since Chandra's Tear would still be guided by its Military Commander, my friend and partner, Aeson. They knew, as I did, that the firm hand of that wise officer would ensure that the project proceeded smoothly and securely. But the bureaucrats in Athens were another matter. They had no problem with Kleon and Ramonojon taking time off, but to their pedantic minds a ship's commander belonged on his ship.

For four days message capsules flew back and forth between Chandra's Tear and Athens conveying my arguments and their counterarguments. They finally gave in when I threatened to lodge protests with the Archons and the provost of the Akademe. I hinted at dire consequences to careers, and implied a level of influence with those in power that I was not sure I had. My bluff worked, but out of spite the bureaucrats insisted I find some way to pay for my absence. I grudgingly offered to make a lecture tour of some of the city-states around the Mediterranean to offset the minute costs of my month's rest.

That matter settled, Kleon, Ramonojon, and I cleared our desks of paperwork and prepared to depart. We arranged to disembark from the ship at the sky dock on Crete and come aboard again one month later from the port in Athens. I considered having a formal ceremony of departure, during which I would explicitly hand over scientific command of Chandra's Tear to Mihradarius, who was my second-in-command. But on reflection I decided that a formal ceremony of leave-taking with the requisite prayers, sacrifice, and taking of omens would make the crew too conscious of my absence and worry them unduly. However, neither did I want to simply vanish from my own ship like a thief in the night, so, the night before I was to go back down to Earth, I had a celebratory feast laid on in the ship's commissary.

The slave cooks did a marvelous job of preparing the meal, which centered around a whole roasted lamb marinated liberally in olive oil and oregano, served with barley bread fresh from the ship's ovens; there were also fresh vegetables from all across the world and little honey cakes dotted with dates. To add to the celebration, Mihradarius himself brought out some jars of Persian wine that had aged for many years in his family estates near Persepolis. He broke the seal on a dark red vintage and let the heady smell waft deliciously from the clay clask; then he poured and mixed the wine with water and toasted me with fulsome congratulations for having brought Sunthief this close to final success.

The whole scene is engraved in my heart with perfect clarity; I remember Mihradarius's aristocratic, upright stance, his flowing Athenian scholar's robes, and the sight of his right hand as he raised up the plate of wine. The last rays of sunlight glinted off the deep crimson liquid while the silvery glow that came up from the ship's deck set off the black figure painting of Mithras on the underside of the drinking vessel.

"To Aias of Athens," Mihradarius said, his voice carrying clearly though the crisp air of five hundred miles up. "Commander, may you well enjoy your rest after long labors."

I bowed my head in thanks and the two hundred crewmen of Chandra's Tear, both my own scientific staff and Aeson's soliders, raised their plates of wine and drank to my triumph from which their own triumphs would flow.

As the sun set, I raised my plate and drank to my crew in the mingled silver light of moon and stars and ship. That dark purple draft of Dionysos flowed down my throat and elated me with thoughts of my soon-to-be-completed achievement. All around me my crew were drinking and laughing, praising me and delighting in their own efforts. O gods, how easy it is for man to fall into hubris. O Prometheus, maker of man, why did you bless us with so little of your divine forethought?

Basking in the warmth of wine and praise, I took a plate of lamb and wandered for a while through the party, graciously accepting the congratulations of all about me and complimenting each crewman in turn upon his work. In one corner of the commissary, seated on two adjacent couches, I came upon Mihradarius and Ramonojon in animated discussion. They formed a strange contrast, the tall, intense young Persian genius, keen and clear with his ideas, and the old Indian man cautiously rounding off the sharp corners of concepts, smoothing the way for Mihradarius's notions to be put into actual practice. In the three years we had worked together they had fallen into a secure practice of continual wrangling from which had emerged the designs for the sun net and the mechanism that would secure it to the ship

"Commander," Mihradarius said as I walked up to them.

"Aias," Ramonojon said, greeting me as friend to friend instead of subordinate to leader.

"Ramonojon, you have no work for the next month," I said. "Why are you sitting here arguing with Mihradarius?"

"There was a matter of the net specifications," he said.

"I did not ask what you were arguing about," I said. "But why were you arguing?"

Ramonojon bit his thumbnail in contemplation. He sat for a few moments thinking intensely. "Habit," he said at last. "Just habit."

Ramonojon lowered his head in mock shame and ate a little of the lamb on his plate. Mihradarius and I laughed lightly at Ramonojon's self-mockery.

"Do not worry about the sun net, Chief Dynamicist," Mihradarius said to Ramonojon. "I shall keep all your concerns in mind while you are gone."

"Thank you, Senior Ouranologist," Ramonojon said. He smiled for a moment, but then it seemed as if a heaviness settled briefly on his shoulders before being dispelled by a shake of his head. "But only I can keep all my concerns in mind."

I wondered what was troubling him, and was about to ask, but at that point Kleon darted out of the crowd and flitted over to us. He was carrying a small plate of olives and sweet wheat cakes, one of which he was in the process of devouring. True to his Pythagorean vows, my Chief Celestial Navigator never ate meat, but that had never stopped him from relishing his food.

"Mihradarius," Kleon said, wiping the last few crumbs of cake from his thin, scraggly beard. "I hope you will keep my ship safe while I am down on Earth."

The navigator's musical voice held an air of joking amusement, but underneath that tone lay a clear note of real concern. It was hard for Kleon to leave the ship he had been piloting for three years; he knew his second navigator to be a competent pilot but not divinely gifted as Kleon had become through years of Pythagorean mathematical contemplation.

Mihradarius nodded patiently to Kleon. "Tell me what you think I should do," he said.

Kleon and Mihradarius settled down to a discussion of the ship's routine, including flight schedules, maintenance work that needed to be done, and so on. Mihradarius was remarkably indulgent of Kleon; usually my second-in-command had little or no patience for such things. I noted it in my mind as further evidence that Mihradarius would one day be an excellent scientific commander.

While Kleon and Mihradarius were going over the rotation schedule for the junior navigators, Ramonojon stood up quietly and faded into the crowd, not wanting to be drawn into such a lackluster conversation.

For similar reasons I also slipped off, ducking through the throng of scientists and soldiers sharing idle talk and grandiose hopes, and made my way to the aft end of the commissary, where the slave cooks waited with more food and wine.

My co-commander Aeson was seated on a couch next to the serving table. Between small bites of plain bread he swept his glance over the crowd, studying his soldiers and officers with an appraising eye. His Spartan spirit kept the men from indulging in excess, and made them remember that they were the crew of a celestial ship of the Delian League.

While I could inspire my scientists with the vision of Sunthief, it was Aeson who kept the whole crew, civilian and soldier alike, aware of the military importance of our work. Watching him, I became keenly aware of the central tenet of Delian rulership: two leaders for every command. There was a pang in my heart, an instant of worry about my absence. Would the ship run as smoothly with one full commander and one second-in-command? But that brief touch of wise caution was swept out of me by the spirit of surety that reigned over my ship.

Aeson nodded to me and handed me a plate of wine. "Enjoy your rest, Aias," he said. "I will keep watch over our command."

I drank the wine to the last drop, put down the plate, and gripped Aeson's elbow as friend to friend. "I have no doubt of that," I said.

Aeson returned the gesture, his scarred, strong warrior's hand giving my arm a gentle clutch of reassurance. The two of us together raised a toast to our crew and to Sunthief and then with the hurrahs of my men still ringing in my ears, I retired to pack my traveling satchel and sleep off the heady wine of confidence.

The next morning Chandra's Tear docked above Crete to take on supplies. Kleon, Ramonojon, and I bade farewell to our comrades and underlings, then disembarked to enjoy once again the pleasures that only Earth could provide. Kleon remained in Crete at the celestical navigators guild to obtain some new impellers for our ship and to catch up on the latest advances in mathematics with his fellow Pythagoreans. Ramonojon and I shared a light breakfast of bread and olives at a small restaurant on the coast; then he boarded a fast ocean ship bound for his home in India. Alone and at peace, I reacquainted my body with the sensations of immobility before setting out to refamiliarize my mind with the luxurious life to be found around the central sea of the Delian League.

My first stop was Memphis in Egypt; there I walked along the banks of the Nile, watched slaves harvest papyrus reeds to be pressed into scrolls, and saw the steamships ferrying gold and exotic foods from the heart of Africa into the Mediterranean basin. I paid due homage to Thoth-'Ermes at the temple in Memphis and gave a ten-year-old lecture on the properties of light-gathering materials to the schoolmasters and junior scholars of that city.

From there I passed on to 'Ierusalem and enjoyed a lively debate with the Pyrology staff at the rabbinical college on the exact motive properties of different forms of fire. We argued for seven hours without a pause and only stopped because night was about to fall and the 'Ebreu holy day of rest began that evening. The next day I and a few other visitors wandered the nearly deserted streets of the city while the inhabitants stayed in their homes praying with their families or went to their temple to worship their god.

The next day I traveled by underground evac tube to the port of Gaza and boarded a Spartan warship traveling to Rome in order to pick up soldiers needed for the war in North Atlantea. The Forum in Rome buzzed with the latest battle news; merchants and aristocrats argued cogently about what strategies the Spartan high command would use to capture the plains of that continent and what means the army of the Middle Kingdom would use to try and stop our armies. Of all the peoples in the Delian League the Romans come closest to the Spartans in their fascination with war.

As I was leaving the Forum, I was accosted by an old veteran who had when a much younger man served under my father's command. I bought the retired soldier a bowl of wine and listened respectfully as he told me of the campaigns of his youth and the battles he had fought to take the river Mississipp.

He was particularly vehement about how easy today's soldiers had it, since he had been in the army before the invention of celestial ships. In those days the enemy ruled the skies with their battle kites and our troops had only the artillery to defend themselves with. Before I left, he asked me how my father was. I smiled and shrugged, not wanting to tell this loyal old man that my father and I had not spoken in over two decades.

Not surprisingly, my lecture to the Roman college was poorly attended as I refused to speak about weapons research. The Spartans would have had my head if I had actually given out any details about an important military project like Sunthief. The night before I left I attended the New Orphic mysteries in the catacombs beneath the Pantheon, then I paid my respects to Zeus of the Capital and sailed away.

From Rome I went to Syrakuse, where I offered the traditional sacrifice of the blood from a black-wooled sheep to the heroscientist Archimedes, one of the first great weapon makers. Few ask for his intercession, but I needed all the divine assistance I could muster for the completion of my work. In the bustling port of Syrakuse I took ship to the Pillars of 'Erakles; from there I traveled on land in the sweltering steel box of a military fire chariot eastward across the north coast of Africa. The soldiers driving the

steam-powered wagon asked me if I had ever been in anything this hot. I, who was planning to capture a fragment of the sun itself, had no choice but to laugh all the way to Carthage.

The citizens of that part of the world are very traditional people. Of all the cities on the Mediterranean, Carthage is the only one to have no modern conveniences. Their tallest buildings are three stories high, there is no sky dock, no evac tubes for intracity transport, no weather-filtering grids of air-silver above their houses. They even refuse to grow animals in spontaneous generation farms.

Some people, no doubt, derive contentment from that primitive existence, but I had come back to Earth to enjoy myself. After giving a very abbreviated lecture and taking as few questions as possible, I fled on the first ship I could find bound for Tyre, the city of my birth.

I reached Tyre four days before my vacation was due to end. The moment I stepped off the boat, I was mobbed by two dozen of my maternal relatives. Young cousins pulled at the blue fringe on my scholar's robe and asked me all sorts of questions about life on a celestial ship. Uncles offered me advice on how to keep my subordinates in line, and my aunts presented me with the names of several eligible women I might wish to marry; after all, I was forty-three and not getting any younger.

To drive home this point my aunt Philida insisted I attend my niece's wedding the next day. She had me on prominent display, holding one of the two-foot-tall red candles in front of Ishtar's altar. Looking down on me from a gallery near the waist of the huge gilded statue of the goddess of love were two dozen young women my aunt had assembled to look me over. By keeping my mind on the solemnity of the occasion, I think I managed to look distant and bewildered enough to disinterest them. Whether that is the case or not, I passed through the ceremony without becoming affianced.

At the wedding feast I indulged like a sybarite in the wonders of Phoenician cooking, supping on lamb with dates and figs, chickens potted with Atlantean tubers, wine aged in cedar casks, and fragrant honey-nut cakes. When my mouth was not full, I fended off the moneymaking schemes of my merchant cousins. To them science was neither a pure pursuit of knowledge, nor a vital factor in the prosecution of the war between the Delian League and the Middle Kingdom. No, to them science was a source of new devices they could sell. I enjoyed immensely ducking their attempts to inveigle me into complex deals that revolved around my inventing something for them, their selling it, and all of us making a fortune.

I stayed with my mother's family for one more day before taking ship to Athens, where I was to give one last lecture, meet Kleon and Ramonojon, and be picked up at the city's sky dock by Chandra's Tear.

At the marina in Tyre I looked over the Spartan high-speed priority transport ship that had been assigned to take me to Athens. The sleek steel craft, its long fire-gold impellers bristling like spines off its bow, would reach the city of knowledge in half an hour's time. But I did not want my vacation to end that quickly; I wanted to savor the past month's pleasures for a little longer before immersing myself in the rigor of the Athenian Akademe. So I told the captain I would find other transportation. A few piers away I came across a Phoenician merchantman that was bound for Athens but would take a leisurely twelve hours to reach that queen of all cities. My identification scroll marked with the seal of the Archons and a few obols from my purse bought me passage.

And that is how I came to be lounging on the open deck of an unarmed antique steamship rather than under the steel aegis of a cannonaded naval vessel when the Middler battle kite swooped out of the peaceful afternoon sky and tried to kill me.

At first the attacking aircraft was just a spot against the brazen disk of the sun; I thought it was a celestial ship, hundreds of miles above the earth, but as it drove down on us it grew larger much too quickly for something that distant. It darted away from the sun and I made out its silhouette against a lone cloud. A coiled serpentine form twenty feet long with broad translucent wings half the length of its body. I knew then what it was, a silk dragon with a human pilot and enough Taoist armament to easily sink this ship.

The dragon looped above the cloud, then furled its wings and plunged straight down toward the merchantman. On the tips of the aircraft's wings its twin silver Xi lances vibrated, roiling the ocean with waves of invisible fury. My fragile merchant vessel pitched back and forth, toppling me onto the foredeck. The rough grain of the oak flooring scraped my face. At the same moment a surge of water came over the side; it drenched my robes, stung my eyes, and diluted the flow of blood from my scratched cheeks.

I pressed my salty robe against my face to stop the bleeding, wincing at the sting of brine. My lungs coughed out a spume of seawater. Again the silver lances shimmered; the realm of Poseidon heeded their silent command and waves rose up fifty feet from the formerly calm seas and slammed into our hull. The ship turned on its side, narrowly avoiding capsizing. Amid the angry rocking, I clawed my way across the boat, hoping to reach the navigation tower amidships before we were swamped.

Hand over hand I crawled across the slippery deck, spewing water and maledictions from my throat. First I spat oaths of condemnation against the shoddy old ship, against its antique engine, so slow that the ship did not even have restraining straps. Then I laid my curses where they belonged, against myself for taking civilian transport. But even as I scrambled and swore, my mind focused on the impossibility of the situation: I was on the Mediterranean Sea, not the front lines in Atlantea. How, in Athena's name, had an enemy aircraft reached the center of the Delian League, and where was the Spartan navy when you needed it?

The dragon's shadow rippled in multicolored grace as it soared upward and coiled into a loop, a serpent biting its own tail. It held that posture for a moment, then unfurled and swooped down over the steamer's paddle wheel. It passed directly over me, blotting out the sun with its shimmering body. I could see the pilot, a small man in a black silk gi, pulling guide wires, turning the Xi lances to bear on our starboard side. I sucked in air and offered silent prayers for my life to Poseidon and Amphitrite, sure that the next blast would sink us.

My ears had been numbed by the hum of the Xi lances, so I didn't hear the shot that saved us, but, O gods, I saw it. On the horizon a thin corridor of air pointing from sea to sky shimmered into sharp clarity. A trickle of hope entered my heart at the sight; that line of rarified air meant that just beyond my field of vision an evac cannon was prepared to fire. My hopes were realized; a steel tetrahedron the size of a man's head flew skyward up that line of thin air. My practiced eyes followed the brightly outlined projectile, and I knew the gunner had done his job well. The twenty-degree incline of trajectory would carry the tetrahedron to a spot directly over our heads at the exact second when the projectile ran out of impetus.

The equations that governed the movement for an object of that shape and material swam through my mind, offering reassuance of our salvation, but they were drowned out by memories of my boyhood self standing up in classrooms and reciting the simplified forms of Aristotle's laws of motion.

A terrestrial object under forced motion travels in a straight line, slowing until it stops.

The tetrahedron ceased its forward flight five hundred feet directly above the dragon. In the clear air I could see the gleam of sunlight reflecting off the pyramid's four faces and six knife-sharp edges.

A terrestrial object under natural motion moves in a straight line forever...

The tetrahedron plummeted down into the kite, tearing silk and bamboo, flesh and bone like a scythe through papyrus reeds.

unless stopped by some force.

The projectile, spattered with blood and festooned with strips of torn silk, struck the steamship's deck, gouging grooves into the thick wooden planks. Jagged splinters flew out from the impact, but the tetrahedron did not break through the thick slats of oak. The tetra teetered on one of its vertices for a moment, then fell over and sat still as if it had been eternally fixed into the ship like the pyramids into the sands of Giza.

The shattered corpse of the dragon lost control of the winds that were carrying it and crashed into our paddle wheel, wedging shards of silk and splinters of bamboo between the turning planks. The wheel stopped spinning, raising a wail of protest from the steam engine as it labored fruitlessly to give impetus to the ship.

That clamor cleared the numbness from my ears and filled my heart with fear. I ran aft, slipping several times on the tilting, sodden deck. Sailors ran past me. Cries of "Abandon ship!" resounded from the navigation tower. Some of the men dived overboard, desperate to get away before the archaic engine exploded.

The Xi lances, still protruding like claws from the broken wings of the dragon, shattered under the strain of the angry wheel. Silver shards rained down on the deck, biting into the loinclothed sailors. I threw my arm across my face and a dozen needles stabbed into my forearm instead of putting out my eyes.

The deck careened to port then starboard then port again as the ocean's currents, free from the power of Middler science, yoked themselves again to the natural flow of the tides. Amid the chaos I kept running until I reached the steam engine.

Twin jets of steam spurted out from the nozzles on either side of the huge bronze sphere that held the boiling water. The streams of hot vapor tried to spin the sphere; the belt of leather that tied the brazen ball to the paddle wheel wanted to be turned by that spinning; the paddle wheel wanted to receive that turning and so turn itself in the ocean and make the ship go. But the paddle wheel was chained by the corpse of the kite and could not accept this gift of movement. This rejection was passed on to the leather loop, which could not move across its pulleys and so passed its stasis back to the engine, which was locked into place by this chain of refusals.

But the steam kept coming out of the pipes, stubbornly trying to imitate the Prime Mover and set all things in motion. Cracks appeared in the ball, rivets popped out, and a dozen little hisses joined the great blasts of boiled water.

I ducked below the sphere, wrapped the hem of my robe around my hand, and yanked open the door in the side of the fire box that boiled the water. Gouts of no-longer-contained fire rushed up into the sky. I rolled to the aft railing just fast enough to avoid being scorched.

The steam from the orb turned into heavy mist as the flame that had kept it boiling rose upward, forming an ascending pillar of fire, a flare that could be seen for miles. The blaze continued to rise until, pushed upon by the air, the atoms of fire dispersed, joining their fellows in the glow of daylight.

I collapsed onto the deck, my seared throat choking on the sodden air. I coughed phlegm into my drenched robes, then lay still, sweating like a Marathon runner. The cloud of steam gradually condensed into dribbles of water. The paddle wheel, freed from the chains of impetus, rolled gently backward, pushed by the Mediterranean tides, and the broken battle kite and its broken pilot fell gracefully into the wine dark sea.

A cheer rose from the crew; I struggled to my feet to acknowledge the accolade, but it wasn't me they were lauding. From the east a two-hundred-foot-long steel ship, bristling from prow to stern with evac cannons and armored soldiers, bore down on us. I sank back in exhaustion and thanked Ares and Athena for our salvation. The navy had arrived.

With Spartan efficiency, the battleship Lysander heaved alongside the damaged merchantman, pulled the formerly panicked, now cheering sailors from the water, and laid a gangplank between the two vessels. During these unhurried maneuvers, I propped myself against the empty fire box, stanched the blood dripping from my cheek with my robe, and watched. The Lysander's presence and bearing restored my sense of safety. She was a long, sleek ship, covered from stem to stern with a canopy of steel to protect her from aerial bombardment. Her steel hull had been painted a utilitarian iron gray. The only adornment on the entire ship was the figurehead on her prow, 'Era, patron goddess of Sparta, arms crossed in front of her, eyes scanning the horizon for anyone who would dare offend against her people.

I bowed my head to the image of heaven's queen, then turned to gaze with personal pride at the onyx pyramid that covered the sternmost twenty feet of the ship. My 'Eliophile engine, my only claim to glory until Sunthief. It had been twenty years since I discovered how to attract and catch the atoms of fire that danced in the sunlight and use them to power ships. Since then every oceangoing vessel built in the navy's shipyards had been fitted with one of my engines. They had become so common that few people even remembered that I had invented them, such are the vagaries of the goddess Fame.

A cough interrupted my reverie. A lightly bearded young Aethiopean wearing the black-fringed tunic and professionally concerned expression of a naval doctor was standing over me with an open satchel of instruments.

"I am not seriously injured, Doctor. Attend to the sailors," I said, knowing exactly what his response would be.

"Let me be the judge of that," the young man said with solemnity that belied his years. Doctors always said the same thing in the same tone of voice and they always had the same casual disregard for orders; the Oath of 'Ippokrates is much stronger than the discipline of armies.

"No great injuries," he said after looking down my throat, rubbing a light metal probe over my cheek, and feeling my limbs for fractures. "Just some scratches and a parched throat."

He pulled a brown glass bottle with the Egyptian hieroglyph for blood incised on it and a clean goose quill out of his leather bag, filled the quill with red liquid from the bottle, and jabbed it into my arm. "Just an injection of Sanguine Humour to speed the healing process," he said, as if I hadn't known that. "Apart from that all you need is some rest," as if I hadn't been resting when he came along.

The doctor turned to go and snapped off a quick salute to a young woman in armor just crossing the gangplank from the Lysander to the merchantman. I almost ignored her; after all, many of the battleship's crew had come over to secure the smaller ship. But she was not wearing a naval uniform. She was caparisoned in the thick steel breastplate, hoplite sword, and two-foot-long bronze evac thrower of an army officer. But what particularly caught my eye was the horsehair-crested helmet and the iron brassard only worn by graduates of the Spartan military college. What was she doing on a naval vessel?

She stepped onto the Phoenician ship and strode briskly toward me. As she neared, I began to make out the person under the steel. Her skin had the terra-cotta coloring that identifies the native of North Atlantea and her long, braided black hair, sharp features, and wiry, athletic build told me she was from the Xeroki city-states. But her eyes were a color I had never seen, golden like 'Elios, but with a glint that I thought at the time was coldness, as if the gates of her soul were two wards of frozen fire.

"Commander Aias?" she asked in a voice that perfectly melded Xeroki syllabling with 'Ellenic enunciation.

I nodded, unable to look away from her cold-gold eyes.

"You must come with me," she said like a judge passing sentence.

"What?"

She opened a thin leather pouch strapped to her belt and handed me a sheet of papyrus. It bore a few lines of mechanical block printing, two signatures, and the seal of the Delian League: two circles interlocked, the left one containing Athena's owl, the right one 'Era's peacock.

The message read:

* * *

The scholar Aias of Athens, scientific commander of the celestial ship Chandra's Tear, is ordered to accept Captain Yellow Hare of Sparta as his bodyguard and obey any commands she deems necessary for the protection of his life.

By order of

Kroisos, Archon of Athens

Miltiades, Archon of Sparta

* * *

I read the letter thrice, hoping to make some sense of it. The idea of a Spartan captain assigned the lowly task of bodyguard was ludicrous; if the Archons had ever set my father such a menial job he'd have boiled into a rage, but this Yellow Hare seemed to accept it like a stoic. And why after three years did I suddenly need a bodyguard? Had the Archons somehow known about the battle kite? No, impossible!

"What does this mean?" I asked her. "What's happened?"

"My orders had no explanation. I was called, I came."

"Do you know how that battle kite reached here?"

"No."

"Do you know why it attacked this merchantman?"

"It must have been sent to kill you," she said. "Now come with me to the Lysander so I can prevent the next attempt."

"To kill me?" I said. "Of all the military targets in the Mediterranean why would the Middlers send a battle kite to kill me?"

"I do not know," she said. "But I was told that attempts would be made on your life. Commander Aias, I must insist that you come with me."

I found myself momentarily unable to move; my mind, honed by long years of Akademe training, needed to understand what was happening before I acted. And to leave the fragile Tyrian merchantman for the safety of the battleship would be to give in to ignorance. But I couldn't defy the orders of the Archons or the Spartan confidence in Captain Yellow Hare's voice; I gathered my traveling bag and followed her onto the Lysander. All the while my heart was churning up possible explanations for this impossible attack.

My soft leather sandals slapped harshly against the steel deck of the warship, but my new bodyguard's bronze leggings made no noise at all, as if the clash of metal against metal was a sacrilege she was too holy to commit.

Leather-armored seamen stopped their work, leaving guns unloaded and decks unswabbed to salute her as we walked down the steel-canopied foredeck toward the battleship's prow. But though they saluted, the sailors gave Captain Yellow Hare a wide berth, as if unsure how to treat the high-ranked landlubber.

We passed by an open hatch in which I saw a ladder that led down to the crew's quarters. Below there would be baths and a place to rid myself of my itchy, salt-stained robes. "I would like to change my clothes," I said.

Captain Yellow Hare shook her head. "The spaces below are too confined. An assassin might be hiding there."

"On a Spartan warship? That's impossible."

"No more impossible than a battle kite reaching the heartlands of the League."

"But--"

She chopped the air between us with her right arm, cutting off my argument. "Your safety is more important than your convenience. You will be able to bathe when we reach Athens."

We marched to the bow, stopping just a few feet in back of the 'Era figurehead. My bodyguard looked out from under the steel canopy and swept her gaze across the sea and the sky. I followed her eyes, wondering what she was looking for; then for just a moment the military lessons my father beat into me came forth and I saw as she did.

There were half a dozen ships within sight; four were merchant ships plying the many trade paths of the Mediterranean, one was a passenger steamer carrying civilians from city to city, and the last was a naval messenger boat, just twenty feet long, only one gun, but fast enough to sail rings around the Lysander. Above us there were half a dozen specks that were most likely celestial ships or moon sleds flying high over the few clouds strewn about the sky. But suppose they weren't. Suppose one of those ships was carrying a Middler assassin. Suppose one of the dots circling overhead was another battle kite. If the first impossible attack had come, how many more could follow it?

"You are right, Captain," I said. "My apologies. I have served too long in positions of safety. I will defer to your judgment."

She nodded curtly, then shifted her attention to the ship's armament, scrutinizing the evac cannons set in drum-shaped swivel mounts every five feet along the port and starboard rails. They looked like twin rows of phalloi at a Dionysiac festival. One by one the tops of the long cannons described circles in the air as the gunners greased and tested the aiming gears. My bodyguard nodded curt approval and returned her unreadable gaze to me.

I began to wonder if this assignment was some sort of punishment for her. The idea gave me a perverse sense of relief since it reduced the likelihood that I was in real danger. But two facts glared down this comforting hypothesis: First, Spartan officers who made mistakes were either forgiven or executed depending on the seriousness of the crime.

Second, and more compelling: that battle kite had attacked a ship carrying merchants, wool, and purple dye. The only thing on it of any great value to the Delian League was an important scientist. But I was by no means the most important target in the heart of the League. Unless the Middle Kingdom had found out about Sunthief.

My thoughts were interrupted by the boatswain shouting, "Brace for speed!"

I reflexively grabbed and held on to the support rail that ran the length of the deck and braced my feet against the corrugated flooring.

He shouted, "Deploy impellers!" and a line of golden wedges sprouted on the prow's fluted waterline. A fiery gleam washed under the canopy, limning 'Era's statue with a divine light. The aura of Zeus's bride flowed backward, suffusing Yellow Hare's armor with a fiery brightness. She stood so still and looked so majestic in the light that I thought, forgive the impiety, that there were two statues of goddesses in front of me.

My eyes grew accustomed to the glow and the moment of inspiration passed. I took a deep sniff of the rarified water that wafted like a bracing mist from the impellers. The fire-impregnated metal thinned the ocean, so the ship could sail swiftly without being slowed by the sluggishly heavy waters.

As the ship sped toward Athens on a carpet of unresisting ocean, I gripped the railing hard to brace myself against the backpush. But Captain Yellow Hare's only precaution against the sudden speed was to lean slightly forward and tense her legs. And that little action stopped her from sliding across the deck or tumbling over the side. Immobile as the earth, she let the cosmos shift around her, heaving Spartan defiance in the face of physics.

The ocean spray leaped into the sky in front of us, rushing onto the deck. It stung my face a little, but my cuts had mostly healed and I relished the sharp touch of speeding droplets. I closed my eyes and inhaled the tangy melange of salt and rarified air; then I cleared my head with a deep breath and started to sort through the strange things that had happened since I left Tyre.

Two facts appeared instantly in my thoughts: Ramonojon and Kleon. Had they also been assigned bodyguards? They were in my estimation more valuable to the League than I was. Kleon was universally regarded as the ablest celestial navigator ever to graduate from the school on Crete. And Ramonojon, despite not being an Akademe graduate, was the most skilled dynamicist from India to Atlantea. If the Middle Kingdom wanted to set the Delian League's celestial ship design work back five years, they only had to kill him.

And Ramonojon was vacationing in India, so near the Middle Kingdom border. If they could get a kite to me here... O Athena, I prayed, bearer of the Aigis, keep my friend safe.

I turned to Captain Yellow Hare and shouted over the noise of the waves breaking against the ship, "Have guards been assigned to Kleon and Ramonojon?"

"I do not know," she said. "My orders were rushed to me from Delos without explanation."

Athena struck me with a sudden revelation. Whatever had prompted Captain Yellow Hare's presence had to have happened within the last few hours. The Athenian bureaucracy knew my entire itinerary; they would have been able to reach me with a message or with bodyguards at any time in the last month. What could have happened in a few hours to bring about this response?

The boatswain called, "Retract impellers," snapping me from my reverie.

Lysander slowed as we neared port. My heart lifted; If there was any place in the world where I could find answers it was in Athens, the city of knowledge.

I stared with wide welcoming eyes at the chaotic jumble of buildings that comprised my adopted city. Towers twenty stories high, built within the last century, made the city appear to be a forest of bronze and steel, and at their bases like newly grown mushrooms around ancient trees were clusters of one-story stone oikoi built millennia ago by the founders of Athens. Most of the citizens wandered through that jumbled thicket of stone, metal, and time unsure of where or when they were.

My gaze wandered upward, beyond the tall metal trees to the spire that dwarfed them all: the sky dock of Athens, the one building at the harbor that stood aloof from the ceaseless clanking of daily life. The tapering steel cylinder towered a mile above the clifflike buildings of the harbor. The uppermost quarter mile of the sky dock was covered with flares and lamps to illuminate the way for approaching ships. Once the vessels were over Athens, those same bright beacons guided the celestial ships in to dock at the top of the tower; the vessels came bearing news and raw materials from the inner spheres, then left again laden with commands from the earth to the heavens.

As Lysander joined the throng of ocean ships entering port, a four-hundred-foot-long gleaming silver arrow, its sides studded with cannonades, detached itself from atop the sky dock, rose into the air, and flew off westward, a warship dispatched to Atlantea to clear the skies of battle kites. No doubt there were on that ship green soldiers being granted their first glimpse of Athens from the air and being amazed at the orderliness that lay hidden in the chaos of buildings below them.

It had been a quarter of a century since I had first been blessed with that vision of unity arising from discord like Aphrodite from the roiling ocean. At that time I was still a student at the Akademe, and my Ouranology class was being taken to the moon so that we pupils, our heads stuffed with theory, might have our first practical experience of the celestial. We traveled on one of the school's celestial ships, a decommissioned early military model without any of the conveniences a modern craft like Chandra's Tear enjoyed.

Most of my fellow students had stared up at the heavens, eager for their first close-up view of the spheres, but I looked down over the railing on the ship's rim at the place we were leaving behind and made sense of the city of the goddess of wisdom.

The narrow twisty streets and the brightly painted buildings, both old and new, were clumped around three hubs of activity: the harbor, the Acropolis, and the Akademe. The city was a pendant comprised of three huge gems surrounded by clusters of smaller stones. I wondered then whether in her idle moments Athena sometimes opened her jewelry box and studied this most beautiful of her ornaments, knowing that none of the other gods had its equal among their jewels.

I had wanted to continue staring over the silvery edge at that cluster of gems, but my teacher pulled me back and strapped me down on a couch as we set off on the ten-thousand-mile journey to the moon.

I shook away my remembrances as the Lysander steered slowly into the harbor of Athens. The piers were, as always, jammed with packet ships from all corners of the Delian League. Egyptian barges rubbed gunwales with Persian triremes, Indian frigates, Atlantean longships, and so many others. And everywhere there were Spartan warships, sending up signal flares to welcome a brother combatant home.

I had heard many captains complain about using ships of the line as messengers between Sparta and Athens. They bitterly resented being stationed in the Mediterranean when they could have been off battling the Middle Kingdom's navies in the Pacific Islands or off the coast of Atlantea. Lysander's captain would have a story of combat that would give his comrades in dull duty hope for battle, though I doubted anyone else would be happy to hear it.

Lonely but confident in this crowd of bullying athletes was a single Phoenician merchant ship, much like the one we had left behind. A clumsy gang of hulking Norse slaves was hoisting a pile of tan bales from her hold: papyrus, the lifeblood of the city's bureaucrats.

The paper was trundled on float carts into the bureaucracy's office buildings, which clustered around the harbor like manmade cliffs, anthills filled with thousands of workers sucking in and spewing out the paperwork that kept the League alive. A web of evac tubes connected the cliffs to one another. The port was alive with hums and clanks as message capsules rushed through the tubes from one building to the next.

Lysander drew parallel to a long stone pier, and ropes were tossed from her deck and tied to the mooring anchors. Then the warship rolled out its gangway, which met the dock with an audible clang. Harbor slaves started to come aboard but Captain Yellow Hare ordered them back.

"No one is to come within thirty feet of the gangway," she said. Soldiers, sailors, and slaves moved quickly away. The orders of a Spartan were not lightly ignored. Only when there was room enough around the plank for her to keep track of every person nearby did she permit me to debark.

So it was that with aching muscles, scratched skin, itchy robe, and a bewildered mind, I set foot for the last time in the city of Athens.

Copyright © 1996 by Richard Garfinkle

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details