![]() Scott Laz

Scott Laz

4/2/2012

![]()

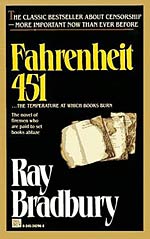

Ray Bradbury's The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 are two of the earliest SF books I remember reading, around age ten, probably because they were the only science fiction books on my parents' shelves. Bradbury, then, and Asimov a little later, would be my "gateway drugs" into the genre, and I read everything I could find in the library by both authors at a young age. I remember liking both books, but preferring The Illustrated Man collection, and rereading Fahrenheit 451 today, I have to agree with my ten-year-old self that Bradbury is much better at shorter lengths. Not that Fahrenheit is very long—for a novel, it's extremely short—but that only makes the limitation more obvious. A simple theme that works well as the basis of a short story can outstay its welcome in a novel, especially if the author fails to engage with the ambiguities and subtleties inherent in it. Much as I was looking forward to rereading this, I ended up surprisingly disappointed. What seemed profound and meaningful to me as a child, now comes across as a problematic and unsubtle screed about the dangers of conformity and mass media. The idea that "the majority," if given its way, would stamp out individualism, seems unrealistic, and reads now like an unconvincing condemnation of communism. This is prime period Bradbury, however, so my arguments with the novel are often overcome by his striking images and the fascinating strangeness of the world he creates. (Spoilers follow, in case anyone hasn't read this novel yet!)

Memorable images abound: the woman who refuses to leave when the firemen arrive, preferring to burn with her books; the sensory overload of the "parlor families" and the "thimble-wasp" earplugs (Bradbury's anticipation of people who are continuously attached to the iPods or cell phones); the stomach-pumping "suction snake" and the mechanical bloodhound, its hypodermic needle moving in and out; the city launched into the air as the homeless intellectuals can only stand and watch. The writing is florid at times, but his use of poetic language is one of the ways that Bradbury's writing stands out, especially when compared to his fellow SF writers of the early '50s.

Bradbury's rage at the dumbing-down of society is palpable, as he portrays the overwhelming distractions of media and advertising, contrasted with the social distaste for engagement with ideas and people, or for the simple pleasures of everyday existence. This alienation and repression leads to suicide becoming ever more commonplace, mirrored at the societal level by the easy acceptance of self-destructive war. "The Army said so. Quick war. Forty-eight hours they said, and everyone home. That's what the Army said. Quick war... I'm not worried. It's always someone else's husband dies, they say." (Sound familiar?)

Certainly most are already familiar with the novel's premise: In the seemingly near future, extreme conformity is the primary value of American society. The role of "firemen" is no longer to put out fires. Buildings have been fireproofed and, in a memorably ironic role-reversal, firemen become fire-starters, responding to reports of secret stashes of illegal books, flamethrowers in hand. For the most part, Americans have not objected to the institutionalized book-burning, agreeing that the profusion of ideas found in them only serves to confuse and distract, creating a potential danger to society, along with discontent and melancholy among individual readers. Better by far to spend leisure time with the jabbering "family" that appears on the mind-numbing high-volume big-screen television programming that has taken the place of engagement with real people and ideas for the vast majority. The constant, gullibly-accepted media bombardment creates a population that no longer questions the decisions of the authorities, nor accepts that they would have the right to ask such questions.

Bradbury's critique of anti-intellectualism resonates in today's America, where a significant proportion of the population have no problem rejecting the expert scientific consensus on questions of meteorology and biology, and even refusing to "believe" easily verifiable facts, such as the birthplace and religion of the President. But Bradbury's concern is not with this type of politically-abetted misinformation, but rather with the sort of dislike schoolchildren can have for the smart kid in the class. When Montag, the fireman protagonist, begins to show signs of questioning his role as a book-burner, his perceptive (and surprisingly well-read) superior, Captain Beatty, recites the party line to him:

"With schools turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word 'intellectual,' of course, became the swear word it deserved to be. You always dread the unfamiliar. Surely you remember the boy in your own school class who was exceptionally 'bright' did most of the reciting and answering while the others sat like so many leaden idols, hating him. And wasn't it this bright boy you selected for beatings and tortures after hours? Of course it was. We must all be alike. Not everyone born free and equal, as the Constitution says, but everyone made equal."

But the response of Faber, a member of the book-preserving underground, sought out by Montag in his attempt to sort out his newly-discovered rebellious inclinations, also seems problematic : "But remember that the Captain belongs to the most dangerous enemy to truth and freedom, the solid unmoving cattle of the majority. Oh, God, the terrible tyranny of the majority." But Bradbury isn't concerned about religious or ethnic minorities; he's upset that the intellectual minority has been marginalized, and implies that the result of such a "tyranny" of the masses would be a mind-numbingly conformist self-destructive dystopia. John Stuart Mill considered a similar possibility in responding to the new ideas of the Utopian (pre-Marxist) communists in 1848, which he saw as potentially stifling to individualism:

"The question is whether there would be any asylum left for individuality of character; whether public opinion would not be a tyrannical yoke; whether the absolute dependence of each on all, and the surveillance of each by all, would not grind all down into a tame uniformity of thoughts, feelings, and actions.... No society in which eccentricity is a matter of reproach can be in a wholesome state."

Is Fahrenheit 451 yet another Cold War anti-communist tract? Consider the society Bradbury portrays: television is not just a diversion from more intellectual pursuits; rather, those who enjoy it are portrayed as utter morons. (And the fact that the only characters we see portrayed this way are women doesn't help.) The complexities of modern urban societies are inherently harmful, with no positive aspects. The normal human urge to conform to a society is not just something to be guarded against, but something which results in mental illness and both individual and social suicidal behavior. It's not that Bradbury doesn't bring up a valid concern, and one with which I strongly sympathize, but his heavy-handed and unsubtle extrapolation of the negative aspects of media-driven conformity ultimately grows tiresome and unbelievable. In a short story like "The Pedestrian," or even the novella "The Fireman," from which Fahrenheit 451 was expanded, these themes come across as valuable food for thought; expanded to novel length, the lack of nuance starts to become problematic.

This interpretation is driven home by the end of the novel, in which the seeming destruction of this society (and most of the population), while portrayed as tragic, also comes across as a sort of necessary cleansing, allowing humanity the hope of potentially going back to a more pristine state. Others may take this differently than I did, but blowing up the world and starting over precludes the possibility of reform or revolutionary change through less apocalyptic means. Bradbury seems to be saying that we brought this on ourselves by abandoning books and ideas in favor of mindless entertainment and meaningless sensory stimulation. We abandoned individualism for conformity and communism. As the cities burn, the non-conformist intellectuals, who have gone into semi-hiding in the countryside, are vindicated. America has not become a dystopia because of the imposition of tyranny by political, intellectual, or economic elites; rather, it is the tyranny of the majority. Democracy has gone too far.

One of the roles of dystopian fiction is that of the cautionary tale, extrapolating from current circumstances to show what might happen "if this goes on." In this case, though, I think Bradbury undercuts his conclusion (and thus his warning) through his use of hyperbole, and by choosing to end the world without considering the possibility of reforming it. But this is a personal reaction. Others may respond positively to Bradbury's ideas, and it brings up some fascinating issues that will always be with us. There are rewards to be had here, and there are reasons Fahrenheit 451 is considered a classic, and is commonly assigned in high school English classes. Any book that raises important issues and produces strong responses—either positive or negative—has value. The longer such debates go on, the less likely Bradbury's future will be realized. And while I think that book-burning is more likely to arise from a tyranny of the few than from a tyranny of the majority, a good society will resist it, regardless of its origins.