![]() Mattastrophic

Mattastrophic

4/12/2012

![]()

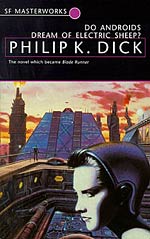

My overarching praise for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is that it uses many different novum (androids, empathy, religion, drugs, environmentalism, human-animal relations, nuclear war, etc., etc.) that all come together in thought provoking, affective ways that, even today, make the novel a rich site for discussion and contemplation.

The central novum of this book is the tension between androids and humans, and it creates great tension, contemplation, and emotion within the book. The former have been built to serve the latter, but even though they are almost perfect copies of real humans they are regarded as less than even the lowest, most mutated human. While a human who follows Mercerism and is concerned with enhancing their empathy cannot kill another human, they can kill an android once they determine that is what it (not he or she, note the pronoun) is. This is done with a series of questions and apparatus that measure a subject’s physiological responses to those questions called the Voight-Kampff test (featured in the first scene of Blade Runner). Therefore, the really tense moments of the novel are not always those where laser beams are flying about, but those during the Voight-Kampff test, when a person’s humanity and life hang on the result. The way PKD built the tension around these scenes, and around one in particular in the middle of the novel, is quite remarkable. I was litterally holding my breath at several points due to anxiety over what would happen next, which is a good thing for the novel (but perhaps not a good thing for me given my daily intake of stress).

The dynamics between the androids and humans as Dick crafts was very pleasing for the simple fact that it doesn’t let you get comfortable with either group. The book starts muddling things when it sows uncertainty as to who is an android and who is a real human (and just what “real human” means and is worth), but it extends this into uncertainty as to who to sympathize with as well. I started out very much sympathizing with the androids, who were built to be slaves and understandably rebelled against their lot in life. The androids, however, give you good reason to sympathize with them, pity them, and despise them. Their hatred of humans is well-founded, too, so no one is exempt from criticism here; as we follow Deckard, we join in his growing understanding of why androids hate and loathe humans. I vacillated between sympathizing with either side, and in the end there are no easy answers as to who is right or wrong, which not only makes for tantalizing contemplation on the issue but for visceral excitement too: if you know who the author feels are the good guys and who are the bad ones, then you can make reasonable guesses as to how things will shake out in the end, but if your expectations are continually in flux on that account, then all bets are off.

The are several other elements of world-building that PKD weaves into the novel come together neatly. The book has a strongly implied environmental and anti-war message in the images of the ruined earth and the ever-present radioactive ash that has killed off most species of animals and threatens to mutate the human survivors. There is a curious instance of technology substituting for drugs in the form of a “mood organ” in which people can dial their preferred emotions, which leads to a kind of emotional emptiness in the end. The concern for animals, indeed the way they are revered, is rendered very believable and affective, which is best demonstrated in a massively nerve-wracking scene later in the novel involving a spider.

Each of these elements on their own sound really far out there, especially considering that the science here is about as soft as it gets, but together they form a believable and engaging world because the characters bring it all together in an affective way. Deckard struggles with his desire for a real animal, his concern for his wife’s refusal to use the mood organ to cure her depression, his concern over his job, and his fear of being killed by an android before he can administer the test that will make it acceptable for him to kill it first. We also follow J.R. Isador, a man mentally affected by the radioactive dust and labelled a “special,” one of the lowest of humans (and he is treated as such) but one who proves himself far more human than the androids who are healthier, stronger, and smarter than he is. While they do feel like characters and not quite real people (sometimes I have problems understanding why they do what they do), they react to their world in believable ways and their struggles over identity, place, and concern for the future makes them sympathetic (perhaps even empathetic?).

The plot is driven by a familiar detective-story framework, but its philosophical and metaphysical contemplations add some wonderful spice the the old forumula. The book replaces the traditional rain-soaked streets of the detective story with stark imagery of a post-apocalyptic (and late capitalist) cityscape, and with SF tropes like laser guns and flying cars mixed in so that the final product is a curious but effective mix of SF elements. The different elements of this book on their own sound very strange, but in what seems to be typical PKD style they come together to form their own believable logic, and in this book they help set the scene for some genuinely engaging contemplations of mind and self driven by pretty good characterization.

The book’s vision of the future does read as dated in several respects: women ares strongly subservient to men in the workplace (like Deckard’s secretary) and at home, the dollar costs of commodities are laughable (or maybe just enviable for us today), and some of the technology like hover-cars or “laser-tubes” (which I can only guess looks like a regular ray gun) not only have the air of a very 1960′s vision of the future, but also occasionally clash with technology that is way outmoded by our standards as well. It is a book of its time, but that doesn’t get in the way of enjoying and appreciating the story since none of it is too far out of whack (like the ultimate computer in Bester’s The Demolished Man running on punch cards).

PKD does immerse you right in there with this ruined Earth and its history, but the logic of it isn’t quite revealed until later. For example, I didn’t feel like I had a grip on why exactly why the androids had to be killed until I was well into the book. I came into this book having seen Blade Runner several times, but even in that adaptation the reasons for killing the androids seems fairly vague: true they killed people during their escape, but that seemed almost secondary to the sin, the audacity, of trying to pass as human. I had problems understanding it in the movie, and the novel doesn’t reveal the full reasons that androids are hunted down and killed (which is very un-empathetic and un-Mercer-like) until you are well into it and Deckard has “retired” a few. I rolled with it, and the payoff was nice, but other readers may not have the patience to wait and find out if that question nags them too much.

The reasons humans loathe the androids on earth isn’t the only thing you have to take on faith in this book. There were lots of unanswered questions, some of them central to the plot and others just concerning verisimilitude: why did the androids choose to go to earth instead of just another colony? Why don’t the companies that make these androids just build them so that people can tell them apart from real humans more easily and sidestep the need for Voight-Kampff tests and bounty hunters? If radioactive dust killed the animals, then why do people keep their animals in pens on the open roof? PKD just kind of plunges you in there and you have to run along with him to get where he wants to go, so you may not want to think about some questions too hard.

Overall, these problems did not bother me much at all (surprisingly), although I can see another reader having problems with them.

PKD is one of those SF authors whose popularity and influence on popular culture seems to keep growing as time passes. His stories keep getting made into movies and adapted into other media, there is a wealth of scholarship and criticism (both academic and popular) on his work, and his books continue to be printed and reprinted. This was the first novel of his I really, really engaged with, and it helps me see why his cultural capital keeps getting renewed. The multitude of weird elements came together through good plotting and characterization to form a thought-provoking and affective story that asks some very big questions. I enjoyed it immensely, and I’ll be chewing on its ideas and haunted by several of its scenes for some time.

So, without further ado, welcome to my favorites list Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep!

Read my complete thoughts on the book at: http://strangetelemetry.wordpress.com/2012/04/12/doandroidsdreamofelectricshee/

http://www.strangetelemetry.wordpress.com