![]() charlesdee

charlesdee

7/5/2013

![]()

In 1971, Michael Moorcock receives from his father a box of his grandfather's, and namesake's, papers. In the box is a typewritten manuscript prepared by the first Michael Moorcock in the year 1903. It is the transcript of a narrative related to the elder Moorcock by Oswald Bastable, an opium-addicted stowaway he encounters while taking a kind of rest cure on Rowe Island in the Indian Ocean. (Rowe Island is Moorcock's -- our Moorcock's -- invention.)

Bastable was a British officer serving in the Raj in 1902. He had been sent on dangerous expedition into Nepal to put down a potential rebellion by one Sharan Kang, a sorcerer leader based in the remote fortress of Teku Benga. Bastable is a shattered man, and over the next three days Moorcock records his remarkable tale. In Teku Benga, Bastable and his men are drugged, lost in the labyrinthine maze of the temples at Teku Benga, and victims of what appears to be an earthquake. When Bastable regains consciousness, his clothes are in tatters, the city is destroyed, and a chasm now separates him from any hope of return. But he is rescued by a vast air ship. The year is 1973.

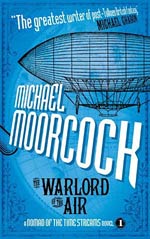

Warlord of the Air is Moorcock writing in a Wellesian mode and the first of his Nomads of Time trilogy. The story brings together three time sequences. Moorcock the writer in 1971 is reading his grandfather's 1903 transcription of adventures that Bastable claim took place in 1973. The reader can write off Bastable story as opium-induced ravings, since what he has to say about 1973 is so far off the mark of what we, and Moorcock, Jr., know. But Moorcock's grandfather is inclined to believe the young man, and we should be as well. Just because Bastable has travelled into the future, it doesn't mean that it is our future. In the same sense, Bastable suspects that the present he has returned to is not exactly the present he left that year before in Teku Benga.

Bastable is awestruck and delighted with the future world his discovers. It is a colonialist utopia. All those benign powers he knew from the turn of the twentieth century control their colonies with a firm but just hand, although there remain a few warlords in China and no right-thinking Englishman could really approve of how things are handled in Russians and Japanese territories. But there has been no serious war for seventy years and as his rescuer, Major Howell, assures him things are going along swimmingly. At that moment a bomb explodes nearby.

Major Howell's face was suddenly grim and white and his dark eyes blazed with anger,

"What was that?"

"Bomb"

"Here?"

"Anarchists, Madmen, European troublemakers, almost certainly...Germans - Russians - Jews, they've all got an interest in the disruption of order."

Damn those malcontents. Bastable instinctively does not approve of them. The rest of Moorcock's short novel will be Bastable's education in the ways of this new world, the flaws in this utopia, and an account of his hero's difficult transition from faithful soldier of the Raj to one aligned with the revolutionary movements of the day.

As an exercise in literary style, this is the most entertaining of any Moorcock book I have read. He is writing in the 1970's what purports to be a transcript taken in 1903. The future he describes, as comically off-the-mark as it may be, is true to the vision we can imagine concocted by an early twentieth-century novelist. He peoples it with stock characters including evil Oriental geniuses, London dandies, aristocratic anarchists, and socialist visionaries, all aided by a technology the we know never developed in the way his characters experience it. At the end of the story, with Bastable once again disappeared into the time stream, Moorcock's grandfather reviews the manuscript in his hand.

I glanced through my notes. Giant airships--monorailways - electric bicycles - wireless telephones - flying machines - all the marvels. They could not have been invented by the mind of one young man.

Moorcock is describing the novel he himself has just completed.

http://www.potatoweather.blogspot.com