![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

11/21/2014

![]()

How to read William Gibson: From Someone Who Has Read Three of His Books

How to read William Gibson:

1. Take a deep breath.

2. Read.

3. Keep taking deep breaths.

4. Keep reading.

5. Don't freak out if you don't comprehend everything. It's going to be okay.

6. Repeat the mantra: "Surrender to the words and it will all make sense later. Surrender to the words and it will all make sense later. Surrender to the words..."

7. Finish the book.

8. Sigh in smug satisfaction.

9. Maybe make tea. You deserve it.

Reading a book by William Gibson is a bit like being dropped into another culture, another time period, another universe, with zero preparation about said culture, time period, or universe. Sure, the characters may look familiar, act familiar, and speak your language, but there are enough minor differences to add up to whole lot of confusion. Gibson situates his readers so that they are spying on his characters, eavesdropping in the middle of their conversations, with no prior context, and the narrator can't be bothered to help because they've got cool new gadgets to talk about. The characters' experiences are just enough alien to ours that we can't understand it. Thank goodness this is fiction, or this could be really dangerous.

Disorienting to new readers who are used to the accessible, handholding style of other popular genre writers, this approach may scare off potential fans who are bewildered by their unexpected arrival to a world with no narrator-provided Lonely Planet guidebook. And no suitcase. It's unfortunate because readers who are not willing to wade through the clarifying (and clairvoyant!) swamp of pre-invented tech jargon and cultural neologisms will miss out on the truly pleasurable experiences that will enthrall the more tenacious reader.

I should know, because it happened to me, with my first Gibson, the ultimate Gibson, Neuromancer (1984). Not an advisable place to start, I know that now, but I managed to comprehend most of it (with the aid of a search engine and some veteran SF readers). Gibson is the king of "showing, not telling," an approach that, at the time, I both loved and complained of. Being early in his career, the novel is uneven, unclear, but less deliberately so, putting readers at a greater disadvantage. The beauty and clarity in his phrasing is appealing, but it is overshadowed by jargony and junky add-ins. For that reason, I postponed the rest of the Sprawl series.

Then, I was forced to read Virtual Light (1993) from the Bridge series, a prescribed reading as I prepared to read all of the Hugo nominees from years ending in -4. I dreaded reading it. I mean, dreaded it. I dreaded it more than I dreaded reading anotherPern novel. Look at that cover. Ugh. Horrible. Another jargony, uneven read that would never appeal to me. I would never read this on my own. But, because I have self-diagnosed book OCD, I read it anyway, and discovered that, in Virtual Light, Gibson is more accessible, injecting wit and positivism into his tale, but sacrificing much of the prescient, high tech offerings for which he is practically worshipped.

Then, I was forced to read Virtual Light (1993) from the Bridge series, a prescribed reading as I prepared to read all of the Hugo nominees from years ending in -4. I dreaded reading it. I mean, dreaded it. I dreaded it more than I dreaded reading anotherPern novel. Look at that cover. Ugh. Horrible. Another jargony, uneven read that would never appeal to me. I would never read this on my own. But, because I have self-diagnosed book OCD, I read it anyway, and discovered that, in Virtual Light, Gibson is more accessible, injecting wit and positivism into his tale, but sacrificing much of the prescient, high tech offerings for which he is practically worshipped.

But I loved Virtual Light. (This is why prescribed booklists are a good thing. I never would have read it on my own, and now it is one of my favorite novels ever hands down not exaggerating I swear on my Sony Xperia with Dragontrail glass.)

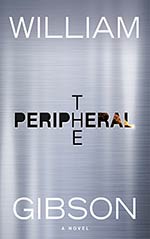

Another decade later, and we have the eagerly awaited The Peripheral (2014), where Gibson's own characters are dropped into the middle of a distant time period, with no explanation, no Lonely post-Apocalypse guidebook, and the people of this future aren't exactly forthcoming with helpful information.

It's as if Gibson is satirizing his readers' plight.

While Flynne's brother Burton, on VA disability for a haptic glitch, is held by Homes in the middle of a track field after a counter-protest with Luke 4:5, Flynne subs for him in a beta trial of a paparazzi player, for which she uses her funny Fab phone. While chasing bugs, Flynne may have witnessed a murder, but the body nano-disintegrates in mid-air. Meanwhile, seventy years in the future, Wilf's job as a publicist is terminated after his client, a celebrity skin artist, botches a match with patchers on a plastic island in the Pacific Gyre. Somehow, the two events are related, and Flynne must visit Wilf's time via a peripheral, in order to help solve the murder and, perhaps, learn enough to prevent the Jackpot.

You know what? I am not going to translate that for you. Read the book, follow my steps, and you'll get it by the last page. I promise.

Let's get the obvious over with. We can't talk about Gibson without talking about his expectations of the future. In ten years, we have 3D printed counterfeit everything, cardboard cars, implanted cell phone signals, a single corporate monopoly on nearly everything, minor extinctions, failing antibiotics, a greater economic divide, a larger Homeland Security force, privatized national parks, a single, state-run social network, and Chinese robot chairs that reconfigure based on height and weight. Colors reflect the evolving culture, like flu orange and Homeland blue. 70 years beyond that, we have moving tattoos, mass extinctions, carbon-consuming skyscrapers, nanobot construction workers, portable hospitals that look like squids, invisible vehicles, AI homunculus drivers, mutating Legos, and android avatars designed by top fashion houses like Vuitton and Hermes.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. That's really cool, although most of it isn't new to regular SF readers. (I can't believe early reviews only talked about the stupid cronuts.)

But Gibson is great for more than just his foresight. He knows people; how they talk, how they think. Forget articles and pronouns. Sentences are short and blunt, like normal people speech:

"What's this you're driving?"

"Jeep Vindicator."

"Like it?"

"Are you crazy?"

"Helps to make conversation," she said.

"It's not cardboard," he said, "it's American."

"Don't they make most of it in Mexico?"

"You just want to shit on my damn car now?"

"That you're fucking kidnapping me in?"

"Don't say that!"

"Why not?"

"How it sounds," he said, between his teeth, and she knew that was just that far from crying.

Even thought is stylized in realism, free of standard, overdone narration:

"A policewoman, State, in a white paper hazmat suit, half unzipped, was standing in the middle of Porter, eating a pulled-pork sandwich. Flynne liked her haircut. Wondered if Tommy did. Then she wondered where you got a pulled-pork sandwich this time of night" (p. 114).

Beneath all that style, the story itself is interesting, complex, although possibly stretched too thin in a few places (something about buying the governor... I dunno) that the reader will barely notice among the parade of picaresque characters who populate the tale. Not only do Flynne and Wilf feel real, stolid, with personalities and struggles that Gibson reveals mostly through behavior, and not through narration, but their minor associates feel just as stolid, flawed, and remarkable. (Although Wilf's friends are too future-future to feel that real). Flynne's friend Conner, the high school hottie turned limbless war casualty turned peripheral enthusiast states "Let's get back where there's all the fingers... Fingers, legs 'n' shit, that's all I want. Brought my catheter. In a ziplock, on the back of the trike." Just that sentence alone--you know this guy already.

Although multiperspective switches add an air of vigor to tales, the narrative structure of The Peripheral might turn off readers as it jolts back-and-forth between Flynne's story and Wilf's story. Likely a stylistic choice to mirror the characters' jarring experiences with time travel, but the hundred or so short chapters with names like "Death Cookie" and "Buttholeville" give the reader just enough time to acclimate, resulting in reluctance when a new chapter, with a different perspective, opens up and requires the reader to reacclimate. It takes work to keep up, and sometimes results in tedious repetition when Flynne and Wilf are witnessing the same events.

But the joltiness is deliberate, and hardly worth complaint. After all, we, the readers, are the peripherals of Gibson's universe. We upload our minds into his world, and work to decipher his environment by spying on the conversations around us. His characters are pristine and untouched by narrator's hands. They just keep doing what they were always doing. Gibson manipulates us instead.

A happy medium between the cryptic Neuromancer and the cyberlight Virtual Light, readers looking for a Gibson to love might be happy with this one, although Virtual Light remains my favorite so far.

Recommended for readers who have teeth in their brain matter, who want something leathery and substantial to chew on. Great therapy for Type A's who need to freaking relax and let Gibson take the wheel.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com