![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

6/20/2016

![]()

Little Green Men are so Roswell.

Bugs have dominated the sci-fi alien landscape throughout its long history, from Wells' spindly invaders toClement's didactic caterpillars to theHeinlein/Haldeman/Card & Scalzi spectrum of buggers. It's a natural fit: with those extra articulated legs and absent the puppy dog eyes, bugs really are Earth's other. Plus, with the exception of sci-fi's obsession with busty cat ladies, mammalian aliens don't appear as often, for to put fur and whiskers on it and authors might run the risk of Disneyfied anthropomorphizing at worse, Petting Zoo People at best, and almost always landing something dumb and unimaginative, like NivPourn's stomping elephants; rarely ever Tepper's eerie horselike foxen.

But while bats get page time in the horror and supernatural romance subgenres, this is the first time I've ever encountered actual, literalAlien Space Bats.

Today we are in a universe that contains us and lots of cool stuff and alien space bats... We are not living in the universe we thought we lived in yesterday. (104)

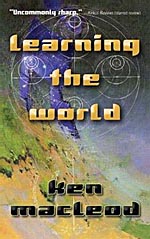

Teen blogger Atomic Discourse Gale lives on a generation starship headed for a nearby solar system with plans to populate its earthlike planet. As the ship gets nearer, they discover the planet is already populated by bat people, which sends the ship's inhabitants into an intellectual civil war. Atomic uses her blog, "Learning the World," (girl needs to work on that title: it's boring) to sway the younger generation into action, while her mother, Synchronic Narrative Storm, manipulates the economy and politics of the older generation, and Atomic's old zero-G instructor, Horrocks Mathematical, is caught in between. Meanwhile, the bats on the planet try to make sense of the sudden arrival of new bodies in their system, spurring their own international conflict. (Yes, the character names are awesome. I'm assuming this is a Banks thing.) (Note to self: read more Banks.)

Although MacLeod uses much of the novel to examine presumptions of solar system ownership by Goldilocks' zone dwellers, and reflects that criticism back upon our own species' (read: Western) assumption of sun-to-Pluto-length manifest destiny, the primary thematic argument in Learning the World critiques the notion of alien invader paranoia -- an odd about-face against much of sci-fi's history of invasion stories, where even the most peaceful invasions harbor some twisted form of social paternalism, i.e. Childhood's End.

In engineering tales, the arrival of aliens is invariably followed by mass panic. (58) (I love that they call them engineering tales.)

MacLeod isn't necessarily saying First Contact will be peaceful, but his argument suggests that such an event will actually cause more internal strife among species, rather than between species, all due to simple social paranoia.

As cute and tongue-in-cheek as the bat aliens and human character names might suggest, MacLeod is true to post-911 sci-fi, especially that of the British persuasion: envisioning a disconnected, inhuman future for humanity:

But talking to my parents was becoming like SETI. They had grown distant and strange. When I was a kid, my pet animals uplifted. My imaginary friends became virtual and autonomous. My real friends upgraded and diversified. They haunted the walls and sent me presences to converse with and meat puppets to fuck. I couldn't evade the feeling that they were giving me less than their full attention. I lit out for the territories. (38)

Also interesting is the case of the trudges: the might-be slaves or might-be beasts of bat civilization, viewed by the almost-post human society of the starship via nanobot cameras that infiltrate the planet via drones. The humans are disturbed by the bat people's treatment of the trudges -- the debate among the humans regarding the trudge origins barely registers in this vegetarian society that condemns the subjugation of any living thing. When the trudges are "accidentally" uplifted by the human nanospybots, they spark a starting ground for common language, which makes this subplot a kind of bridge between the classic Sirius and the more recent Bête, but, although it never quite goes there, the subarc dallies too closely to the edge of the ineffective and derogatory "meat equals slavery" motto, but all without the bother of discomfort to explore this concept fully.

...which is the essence of this book. More tongue-in-cheek than knuckles-to-forehead or guts-in-heart, perhaps it's not fair to expect more from what is a literal extrapolation of a geeky inside-joke, but taking on the task of refuting a century of alien invasion disaster scenarios by reframing the problem within the context of the very real human tendency to in-fight is tantalizing and clever (...though certainly not new: even old H.G. emphasized the horrors of mob mentality in War of the Worlds)... and deserves more thorough treatment. If the social struggle is conveyed only via civilized blog banter and economic manipulations, then perhaps this is not a realistic struggle. Moreover, while the accidentally uplifted trudges are an efficient solution to SF's chronic language barrier, the overall process is glossed over -- not that I desire more technical detail, jesus no, but the presumptive ease of communication between alien species -- depicted in the way we converse with toddlers -- dissolves that sense of otherness and deflates the central argument: that the biggest danger in a First Contact scenario is our own paranoiac danger to ourselves. I mean, the others are just cute bat people who haven't even achieved the atomic age. Of course humans are the problem.

"Defaults, defaults, everyone's got defaults." (210)

The story (and the argument) works because it's lopsided: the humans are more technologically advanced than the bats (although some characters contend that the bats' budding atomic tech is the most dangerous moment in social evolution). A clash between cultures of equal capability, or with the humans at the lower end of technological and social sophistication scale, would make for a real struggle that better supports the thematic premise. Instead, Learning the World ends where positivism and power reigns on the side of the humans -- the human leader practically kissing bat babies at the conclusion; sucking teeth at the idea that more "others" are coming -- yielding to the same superficial ease that weakens utopian narratives and drives the chauvinistic tales of the Golden Age.

It might be chewier than a 350-page inside joke, but the plot and characters run thin, and Atomic's blog entries --readable and likable though they may be --take up unnecessary space where the plot would benefit from some real strife. Plus, on a personal note, after a month inadvertently devoted to reading about elephant aliens (Footfall, coming soon to a cranky blog review near you) and space spiders (Children of Time, coming eventually, maybe, I think), this falls square in the middle of the quality scale of animal-pomorphized alien culture, first contact books.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com