![]() Sable Aradia

Sable Aradia

7/11/2016

![]()

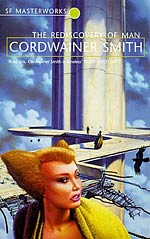

Read for the SF Masterworks Reading Challenge.

I had to read this whole book before before I could decide whether or not I liked it, it was just so weird. But when I had finished the last story in it, I started flipping back through it to find a reference to one of the characters in the last story that I thought I remembered from an earlier one, and I found myself stopping along the way to read some of the passages I really liked. That tells me everything I need to know about what I thought of it.

Cordwainer Smith is the pseudonym of Dr. Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, a man with a colourful history. Although he was born in the U.S. he spent most of his childhood traveling through Europe and Asia. His father was the legal advisor to Sun Yat Sen, founder of the Chinese Republic. At the age of 17 he brokered a silver loan for China on his father's behalf. At the age of 23 he had a Ph.D. in political science and later, he was the professor of Asiatic Politics at John Hopkins University. He became a Colonel in U.S. Army Intelligence, despite his partial blindness and general ill health, and when WWII broke out, he used his position on the Operations Planning and Intelligence Board to maneuver his way into a posting as an intelligence operative in China. He was a major by the end of the war. Later he wrote Psychological Warfare, which is still regarded as the most authoritative text in the field.

I'm telling you all of this because it comes through in his writing. Smith has created an amazingly vast universe here, with ten thousand years of real history, that makes Westeros look like a measly pimple by comparison. This is not a novel, but a book of short stories, collected to be read in chronological order of the events they describe. They would seem to have little to do with each other, but every story has a bearing on every other story. The most impressive thing about this, I think, is that Smith did not write these in chronological order, so this whole vast universe was in his mind before he ever put pen to paper. It rivals the planning of Tolkien.

I'm not usually a fan of very-far-future stuff. I don't think we have any real way of knowing what people ten thousand years from now will be like. But that's exactly what Smith is exploring. Throughout the stories, the common theme is probably, "What does it mean to be human?" With caveats: "At what point are we no longer human?" "At what point does one become human?" and "Do we remain human if all that is left of us is a consciousness?" In the 1960s, Smith was writing about human consciousnesses being stamped into sophisticated machines, and about people being forced into a synthesis with machines, long before cyberpunk, cybernetics, or AI. He was writing about animals being engineered into the forms of people to create an underclass that it was morally okay to enslave. He was writing about how humans might take their animal companions to the stars with them, and how those animals might be more important than we think. And the best part is, there are exactly two alien species in the whole book, neither one of which act in a way that is at all fathomable to humans. Above all, what comes through is a deep respect for earthly life.

The politics that Smith invents reflect his knowledge and interesting history. The Instrumentality, which rules humankind for thousands of years with an iron fist vision of perfection and harmony, is clearly influenced by what a political scientist might know of China and its long history. He points to this by making a vague reference to some ancient disaster in which China fared better than other countries or civilizations.

It can't help but suffer from the limits of its time, however. Strangely it's the technology in the first story, "Scanners Live in Vain," that is the most jarring. Sophisticated instruments that read all vital life processes and all forms of radio waves, ambient radiation, etc., are marked by needles that swing up and down a scale, like a 1950s pressure or power gauge. Still, who's to say that the designers of future technology might not have deliberately gone with this retro look because it's more intuitive than blinking lights, and takes less power to maintain?

It's the social stuff that I find more jarring, however. I find it difficult, as a modern person, to imagine that in the far, far future, with technology being so advanced that it seems like magic, the greater purpose for women would still be to support and improve men, which is implied in more than a few of the stories (though, to be fair, women become leaders of revolutions, significant scientists, pilots, and Ladies of the Instrumentality as well). And I also find one particular story, "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal," creepy in its 1960s prejudices and gender politics. (For those who are interested, contrast Lois McMaster Bujold's "Ethan of Athos.") On the other hand, his race politics for the early 1960s are downright progressive.

He's just a good writer, too. He's a poet. He makes up words because he likes the sound of them and gives them meaning in his futuristic society. Some are words he's pulled from other languages, as English is prone to do. Some are nonsense words. Reading him in places is like reading the Jabberwocky. His people are described simply and are known more by their actions and thoughts than their appearances; but his landscapes are vast and magnificent and frightening and claustrophobic at turns. His societies are complex and interwoven. If I had a criticism there, it would be that at times I think his people fall into line too easily with the manipulations being applied to their lives, but I suppose that's an occupational hazard for a man who literally wrote the book on psychological warfare. I think groups of people are easy to manipulate, but I think individuals are harder. (Though I will own he tries to allow for that; "The Dead Lady of Clown Town" is all about that very thing, as is "The Ballad of Lost C'mell."

Much of it has a fantastical, surreal quality to it that is probably an acquired taste. If this were fantasy, we would reject it utterly because of how implausible it is. As science, however, it has somewhat greater credibility with us, though much of it is still so weird that it takes a shift in perspective to enjoy. But unlike with Gene Wolfe, I made the shift, and I love it.

This book was hard to get. I finally managed to order a hardcover copy online, and it arrived in excellent condition but with no book jacket, stamped with the signs of Kent University. I guess that means it's not been popular enough to stay in print. And yet I see so much of his stamp on later works of science fiction and even fantasy! This is exactly the reason I started the Science Fiction Masterworks book club.Discovering writers like Cordwainer Smith is what it's all about.